“Angelo My Love” is actor Robert Duvall’s second directorial effort, an in-depth look at New York City’s rarely-covered gypsy community, with a wise-cracking twelve year-old kid as its centerpiece. Duvall’s 1977 directorial debut, “We’re Not the Jet Set” (to be reviewed later on this site), was a documentary about a wealthy Nebraskan rodeo family; “Angelo My Love” is a strange hybrid of documentary and fiction. (Neither have been released on DVD, though “Angelo” can be viewed on YouTube).

The title character is played by Angelo Evans, a real-life Gypsy kid then living in New York City; his family in the movie is played by his actual family, and the two other central characters are played by Gypsy siblings, Steve (Patalay) and Millie Tsigonoff. Duvall devised fictional situations for his cast, but as he has noted in interviews (and on a delightfully pandering Phil Donahue TV special featuring him and the cast), the plot was derived from actual anecdotes and stories he had heard from Angelo and his family while researching the film. And he was adamant about the film being as loose and natural as a non-documentary can be. In a 1991 interview with Bomb Magazine’s Daisy Foote, Duvall said that “right before the cameras would roll, I’d yell to the gypsies, ‘No fucking acting!’ I didn’t want them messing with it.”

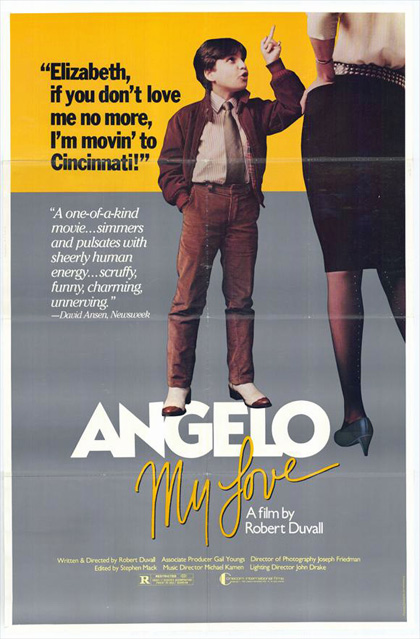

The project was born in 1977, when Duvall, walking around NYC’s Upper West Side, observed a street dispute between Angelo–then just eight years old–and a considerably older woman he regarded as his girlfriend. “If you don’t love me no more, Patricia,” he threatened, “I’m gonna move to Cincinnati.” (That quote later became “Angelo My Love’s” poster tagline.) Though Duvall was not planning to finance another personal film project, as “We’re Not the Jet Set” put a considerable dent in his wallet, he was immediately hooked on the idea of building a film around Angelo. “I thought, ‘This kid has to play the lead in a film, because nothing like this has ever been on film before,” Duvall told Steve Fishman of New York Magazine (“Prince of the Gypsies,” March 7, 1983). Over the next three years, he spent a great deal of time with Angelo and his clan, and began writing a fictional story about Angelo embarking on a cross-country trip. But then his girlfriend (and later wife) Gail Youngs convinced him to frame the film more like a documentary, chronicling the fascinating stories he’d gathered from Angelo.

The resulting film is shambling and episodic. For most of the film, it’s hilarious just watching Angelo be himself. He struts into the neighborhood discotheque like he owns the place, delighting the denizens; he wears fancy little suits with the collar up; he talks tuff and is not afraid to stand up to older, larger people, coming off like a mini-Joe Pesci in “Goodfellas.” (I was reminded of a New York Magazine article I read four years ago, about a fourteen-year old brat named Alex Goldberg who already knew how to hustle his way into star-studded parties). However, Duvall doesn’t let the audience forget that Angelo, despite his bravado, is a kid through and through. He’s afraid of ghosts, for instance, and he’s seen crying on two occasions (although Duvall admitted–in the same 1983 New York Magazine story–that he had to goad the precocious Angelo to show more emotion at times).

The only semblance of a plot has to do with a stolen family heirloom. Angelo was going to propose–at the tender age of twelve–to his girlfriend, with his grandmother’s ring, but it is seized by a brother and sister from a rival Gypsy clan. Angelo, who witnessed the theft, is called on to testify at a large, trial-like meeting between his clan, who is Greek, and that of the accused, who is Russian. They yell and curse at each other like two mafioso families. Then, Angelo and his older brother follow the thieves to Canada but are unsuccessful at retrieving the ring. The film ends with a showdown between Angelo and the Russian thief, and he emerges victorious, but he is scolded by his mother for risking his life for such a silly reason–and anyway, the ring isn’t rightfully his until he turns fifteen. Again, we see that Angelo is a good egg at heart, crying with remorse, aching to please his mama.

Some of the plot devices in “Angelo My Love” are clearly fictional, but they serve to inject heart into the story, to show the limitations of Angelo’s swaggering demeanor. In the most effective scene, early on, we see Angelo at school, and learn that he is illiterate; his teacher asks him to read from a book and he describes the illustrations. Angelo’s classmates, at first delighted with his sassy rapport with the teacher, start to look concerned. Eventually Angelo grows too flustered with the teacher and decides to drop out, and he and his brother are seen gleefully running through the streets, hanging out with their family and accomplices, watching them play music. It’s a touching, authentic look at how many Gypsies are encouraged by their family to drop out of school, so as not to immerse too much with non-Gypsies. (The real-life Angelo said on the Phil Donahue special that he was encouraged by the film to seek out a tutor).

But in some scenes, you wish that Duvall had cut back on the naturalistic approach and fabricated more cohesive drama around the characters, while in others, the dramatic structures he injects seem forced and awkward. The chase to get the ring back, for instance, is both contrived and confusing, as is the concept that Angelo would fight the much larger Russian thief in an alleyway. At other times, Duvall’s shaky, hand-held camera lingers on conversations for way too long, well after their dramatic purpose has been established, a la John Cassavetes. The aforementioned trial scene is adept at capturing the Gypsies’ cadences and speech patterns, but it goes on for an eternity without really taking the story forward; the same is true of a later scene where Angelo and his sister befriend an old Puerto Rican widow in a pizzeria, trying to lure her into their mother’s fortune-telling parlor. A subplot about Angelo flirting with a country singer seems gratuitous, perhaps lifted from “Tender Mercies,” which Duvall was involved with around the same time. There should be more about the Gypsy culture, more about how threatened it is by prejudices and the pressure to assimilate, and a bit less of Angelo being cute.

Because “Angelo My Love” is sometimes riveting, sometimes inconsequential, it naturally drew a mixed reaction from critics. In the New York Times’ April 27, 1983 review of “Angelo,” Vincent Canby wrote of the title character, “He is physically small but he has such a big, sharply defined personality that he seems to be a child possessed by the mind and experiences of a con man in his 20’s. Then, as the movie goes on, one sees Angelo moving from glib, smarttalking self-assurance to childhood tears and back again, all in the space of a few seconds of screen time. This, too, may be part of Angelo’s con, but it’s also unexpectedly moving as well as funny.” David Denby, then writing for New York Magazine, was more critical of Duvall’s awe of Angelo: “We’re supposed to be charmed by an eleven-year-old baby macho who snaps his fingers at grown women. In this case, as in others, Duvall may have miscalculated: He makes the lying, thieving, superstitious Gypsies depressingly petty and argumentative rather than poetic or inspired.”

But though it was only a moderate success, and not widely available, “Angelo My Love” still pops up at Gyspy-related cultural events, and its fair and even-tempered approach to Gypsies must have been pleasing. (Although Duvall wasn’t as immune to Gypsy stereotypes as he might have seemed–the same New York Magazine article noted that “it was often wearying [for Duvall] not to know whether his good intentions were being traded on, whether he was a companion or just a mark. ‘If I weren’t trying to do something from my point of view, artistic or different and novel, I would have no interest in these people. I probably would have disdain for them.'”)

The movie also has some unexpected fans. Anne Rice refers to “Angelo My Love” several times throughout her 1985 novel, “Exit to Eden.”

Duvall has since directed two other films–the critically-acclaimed 1997 religious drama “The Apostle” and the 2002 crime drama “Assassination Tango”–but never returned to documentaries. He should; something tells me a self-financed pseudo-documentary like “Angelo My Love” wouldn’t break his wallet these days. Angelo Evans has since appeared in the 1986 comedy “Saving Grace” (not currently on Netflix). Steve Tsignoff acted in “The Stone Boy,” a glum movie about a kid who accidentally kills his older brother, a year later. Little to nothing has been heard about Angelo, Steve or the rest of the cast in nearly 30 years. Perhaps Duvall should film a reunion with them.

how can i find a copy or watch We’re not the Jet set? I really want to see it