In 2015, I received a comment on Hidden Films’ “About” section from a filmmaker I’d never heard of, Paul Bunnell. It read: “How about a story about the lowest grossing film of 2012 and the last movie shot on Kodak Plus-X 35mm black-and-white Film? P.S. It’s not on Netflix (anymore). ;-).”

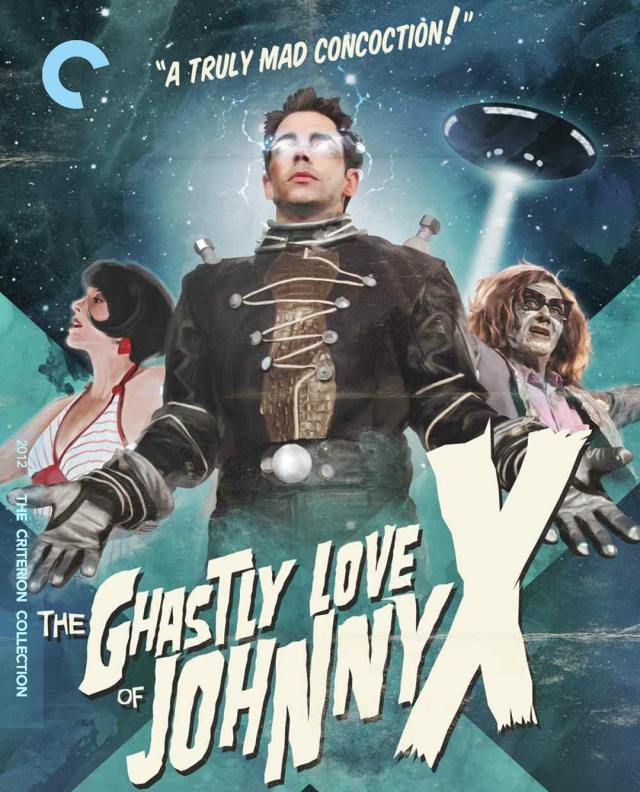

Never mind that, four years later, you can stream Bunnell’s kooky, high-energy sci-fi musical “The Ghastly Love of Johnny X” cheaply on AmazonPrime, YouTube and just about every other existing digital service besides Netflix. I still qualify it as an “under-the-radar” film because it deserves–nay, needs to be–watched on the big screen or at least via a specialty DVD package from the likes of Criterion. Surely, it should not be idling away in obscurity on streaming sites overloaded with newer, flashier, higher-octane content.

The story of Bunnell’s eight-year toil in getting it made (between 2003 and 2011, including a break for refinancing and new location scouting), of the agonizingly short theatrical runs in 2012 and 2013 (several news programs and publications ran cheeky features highlighting its $117 total gross) and of its distinction for grabbing the aforementioned Kodak stock before the makers of “The Artist” could get their grubby hands on it, is enough to fill up a 20-page Criterion Collection booklet. And Bunnell’s tales of these low moments as well as the highs—working with character actor legends like the pint-sized Paul Williams (as a bizarre talk show host) and the late Kevin McCarthy (as an alien grand inquisitor), for instance—could fill up an entire director’s commentary.

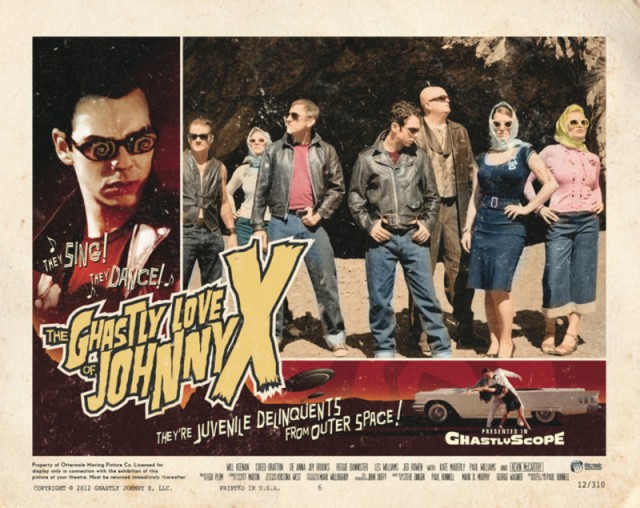

There are other factors that deem it Criterion-worthy. It’s a pastiche, yes, but consisting of a unique melange of influences you don’t see in standard pastiches: “Grease”-style, diner-set dance numbers; intergalactic warfare; telekinetic mind control and zombie rock n’ roll. It’s gentle in spirit, non-violent (the action scenes are of the “BOW!” “BAM!” 50s’ comic book variety), and takes itself just seriously enough to register as “fun” but not “campy.” And the hard work put into it is evident in every frame.

Bunnell still screens the film every now and again at festivals and one-off showings, for low reward. He maintains that he, willfully, was the only staff member not paid a cent for his work on it, but that only emboldens his pride.

I watched “Johnny X”–his proudest creation to date–as well as several other shorts he directed and a plethora of bizarre comedies and comedy-horror hybrids that he acted in, from 1986 up through now. (Several of them were made by Mark Pirro, whose films–especially “The God Complex”—I enjoyed immensely).

After interviewing Bunnell in mid-2017, I decided to help try to get the film on Criterion’s radar, figuring that, should a release miraculously happen, that would be the ideal time to publish this interview. But this was a high-stakes mission that has not yet yielded results, and I do not want the interview to become too dated. The following are excerpts from two conversations.

SAM WEISBERG: If I am to understand the CBS News clip I saw correctly, did “Johnny X” first play in Kansas?

PAUL BUNNELL: No, the movie premiered in March 2012, a few months before [the Kansas International Film Festival, October 2012], at the Cinequest Film Festival. It’s played a couple dozen film festivals. I just came back from Indiana where a college screened it as part of their film program.

Anyway, in Kansas, we won the audience award for Best Film. The prize was a one-week run in their theater. That was great and all, but it was before we were doing a formal theatrical release [in 2013]. It got played for the public and they didn’t advertise it and no one really knew about it, and it collected only about $87 in ticket sales for that particular week. That’s how it got reported to the box office and this lady from CBS did a story about it being the lowest grossing film in 2012. It kind of snowballed from there. I was able to use that angle to get CBS to do a morning story on the film, and that got about six million viewers, and it ran on the Oscars. It’s kind of funny. If it had made an extra $10 or $20 I wouldn’t have been able to do that.

SW: Wherever it plays, it seems to get a pretty overwhelmingly positive response, at least among the audience.

PB: Let’s face it, it’s not a commercial movie. It was a very low budget movie, I had very limited time and resources. I was able to get it made and theatrically released. And there are 35mm prints of the film. In theaters, we either ran it with a DCP—digital cinema package—or with film prints, in theaters that still do that, when I approve it. If any damage happens, those prints are very expensive to replace.

SW: I know it played NYC’s IFC Theater In 2013. How did it do there?

PB: I don’t think it did particularly well, because it was a late show and I don’t think a lot of people turned out for it. Part of the problem is, as much as you think the movie should be a midnight show type thing, I don’t think it works well late. It’s not action packed, it’s not weird enough to be a “Rocky Horror” thing. It’s just a unique thing that should be played earlier in the day.

SW: What was the most positive reaction you got in any given city?

PB: I think at the Egyptian Theater, in Hollywood, 2013. It was a real big deal, we had Ego Plum play before the movie. It was sort of to kick off the home video release. And we had a costume display in the lobby. We had over 300 people turn out for that. It looked and sounded great.

The other screening that went really well was the Chinese Theater, for the Dances with Films festival [in 2012]. We sold out that screening.

SW: What are the key differences between 35mm and DCP?

PB: Well, it can have a little flicker and strobing, it might look a little softer if your projectionist isn’t up to speed. But if they’re shown back to back under the most perfect of circumstances, I personally prefer the film print. But the DCP used a few cheats to fix things we couldn’t fix in the film print. There were some timing issues, and there was a big gash on Sluggo’s [Jed Rowen’s] head, he hit his head. And when he leans in to the car to talk to Kate Maberly, you see the gash on the film print. But we digitally erased that on the DCP. Also on the film print, the opticals look a little softer. We had to go from an internal file back out to film. On the DCP, we went directly from those files and they look really sharp, everything matches perfectly. But the film print is great for purists to see.

SW: Have you shown it in 35mm in any theaters?

PB: I have a theater at my house, a full-blown 35mm triple decker changeover screening room with full Dolby digital capabilities. And I can run “Johnny X” for friends there.

But as far as professional theaters, the last time it played in 35mm was at the Egyptian. It’s rare I let the film go out anymore. [The projectionists would] have to be able to handle archival prints. There are only five prints and they were $2,500 apiece.

The Library of Congress has a print in their permanent collection and the Academy has all the original camera negatives, a fine-grain print and probably a protection print in their archives.

SW: It was the last film made on Kodak Plus-X…

PB: It was photographed on Plus-X negative, which gave us a finer grain. For a few scenes, we cheated and used the Double X film stock, because we didn’t have enough lighting.

SW: Was that when you went back to do to the 2010 shoot?

PB: Yeah, we had 90,000 feet of Plus-X and only a very small portion of the movie was shot with Double X.

SW: When did you fall in love with that particular stock?

PB: There were two options from Kodak, either shooting with slow film or fast film. We decided to shoot with slow film because it gave us a finer grain picture. The challenge was, we needed more lighting, and also we were shooting with anamorphic lenses, and you need a lot of light to fill a lens like that, especially with very slow film. We had a lot of light power, that was a lot of our budget. You have to have a lot of skill in lighting, to light black and white. My DP [Francisco Bulgarelli] was really good and I picked him. I think it was one of his first jobs and he did a fantastic job on it.

SW: Did you ever deal personally with the producers of “The Artist” that wanted the same stock?

PB: No, all I know is they were testing black and white stock at the same time I had purchased all the Plus-X. Because of it being unavailable, they thought they’d shoot on color stock anyway, they were satisfied with how it looked. They took all the color out of the digital. They cheated it; they computer-converted it to black and white.

We did it all black and white, which is problematic, because there’s no color version of the movie. Distributors always want to know, “Is there a color version, to release it in the foreign market?” And I say no. The black and white films don’t sell, really, so I’ve had a problem with the foreign market. But I made the movie I wanted to make and thought people would enjoy and don’t really apologize for it. It was a learning process and I intend to be better for my next movie.

SW: What markets have you sold into so far?

PB: North America, though I don’t think it’s been released in Canada. I think the rights are held by Strand Releasing, only the video and digital broadcast rights. I held on to the theatrical rights, so I can screen it anywhere theatrically—and I have been.

I’m hoping to make a deal with a company called Arrow Films, sort of the Criterion of the UK. If I do it will come out on Blu-Ray for the first time in the UK and the states. The movie looks absolutely fantastic on high definition.

SW: Having made the film, do you get a fair amount of interest from film stock enthusiasts?

PB: No. People are certainly curious about it. At the end of the day, it’s just a black and white movie, but it’s not like it’s any special looking—I mean, it’s very nicely shot. Some of the scenes look really gorgeous projected on film, when it’s done right. But DCP is an accurate representation of the movie. We scanned the 35mm print and tried to replicate the look of the film as much as possible.

SW: What was the final budget, all told?

PB: I don’t really have that answer for you, to be honest. I never added everything up. I know we put in a little over a million. The imdb says it’s $2 million, I don’t think it’s that high, frankly, but I couldn’t get a realistic number. I think it’s rounded off to $2 million. The way it looks, it should probably be more like a $6 million movie.

SW: What drove the cost up? The expensive film stock?

PB: Well, you know…paying people, post-production, some of the PR that we did. We wanted to get a camera crane, that added a little extra. We ran out of the foil backing for the Damnation’s Hole set. The production designer underestimated what it would take to do that. He had built half of it and needed several thousand dollars more of foil.

-

A climactic scene set at Damnation’s Hole.

I had to pay everyone. Except myself: I did not get a salary. I put in years of work on it and made no money. To this day, certain actors are still getting residual checks, for like $5.74. And I’ve gotten no monetary rewards. Not that I’m expecting it.

Next time, I’ll take a small salary. I worked hard on that movie and sometimes I’m a little disappointed that I didn’t pay myself.

SW: Was there pressure on you to finance it that way?

PB: No, I was doing what I felt was the right thing. I didn’t want to take money from my friends. I consider my “paycheck” to be having a 35mm print of the movie, that I can hold in my hand. I enjoy having those reels of film that represent nine or ten years of my life.

The financing was done by myself and my wife [costume designer and executive producer Kristina West] at the time. Unfortunately, last year [2016] we got divorced. She and I invested $130,000 of our own money to start the shooting in 2004. That was as much as we could do. I was ambitious, I was optimistic, like, “We can make this movie for $200, 300,000.” But it just got too expensive. So then the movie got on hold while we looked for more money. And it wasn’t until six years later when I was thinking I was gonna have to give up—first of all, the actors were getting older, people had moved on. But I had all this footage in the can, I had one-third of a movie that I shot and put a lot of work into. We even borrowed money against our house. And to throw that footage out and waste that money would be a bad idea.

Then, my friend Mark [Willoughby, also an executive producer on “Johnny X”] gave me $1 million to finish the movie, at the last minute. It was funded through movie memorabilia, in a roundabout way. He owned a very well-known book, movie and poster store in Hollywood, they’d been open since the ’60s and they were closing and had a big auction of all their stuff [in 2008], and they got around $4 million. So he decided to take a small chunk of it and invest it in my movie. We had a handshake deal. Bless his heart.

SW: How did you come up with the story? I saw a little “West Side Story” and “Grease” in there, clearly a little “Invasion of the Body Snatchers.” How’d you combine those particular genres?

PB: In the very beginning, it was a totally different story. I started with this crazy idea about a space alien girl that comes to earth and falls in love with an earth boy, and I just wanted to call it “The Ghastly Ones,” based on a “Teenagers from Outer Space” ‘50s thing. Then it went to “Ghastly Love” and then “Ghastly Love of Johnny X.” I brought in a writer on the original script, I wasn’t crazy about it, I brought in a different writer, I was so-so with that, and then a different writer. I basically had four different screenplays and I started piecing them all together to make a coherent story. The original idea was dark and kind of grim, and I changed it to a lighter, happier story.

SW: What was grim?

PB: Well, these kids were a gang of outer space performance artists and they’d go to different planets and they’d steal bodies of recently deceased celebrities. And they’d hook [the corpse] up to a rig and have an underground sort of show. “Once again, for the last time, the late, great Dean Martin, ladies and gentleman!” And you’d have this weird corpse doing things with pulleys and tubes. That idea stayed in the movie but more as fantasy, not so realistic. I didn’t want to make a movie about death and ugliness. My dad had just died and 9-11 had just happened, the world was in a bad way at the time. I wanted to make it more fun.

I added one more music number, besides the concert scenes, where the gang comes in to the diner and all of a sudden they’re singing. We added another musical number, and then another and another. I would take a scene out that was boring and put a song in there. I wanted them written in a Broadway musical sense, where the story was being told through song and not being stopped.

SW: How’d you write the songs?

PB: I had good ideas in my head about music and rhythm. I hired a choreographer recommended to me [Carolanne Marano] who had only done musical theater, never a film. For me, it was really cool, because I’d show her the set and she’d come up with the dance moves, and all I had to do was figure out how to shoot it. I didn’t want it to be too over the top or crazy, because most of the actors were not professional dancers. I wanted it simple but clever. We’d rehearse the numbers and I’d videotape it.

It was actually easier to shoot the dance numbers than the other stuff! The concert scene with Mickey O’Flynn [Creed Bratton] was gonna be way more sophisticated originally, but my line producer only allowed me one day to shoot the concert and two days to shoot Damnation’s Hole. I decided to do a split screen to make the concert scene a little more exciting.

SW: Did you write the music?

PB: No, that was all written by Scott Martin, based on the scenes in the script that I gave him. Ego Plum did the score and the musical arrangement of Scott’s songs.

SW: Are you or the songwriter a fan of the band Ween? I noticed a “bah-shee-wah-nee-wah-nee” in there, which is from a Ween song [“Up on the Hill.”]

PB: Never heard of them. I think “bah-she-wah-nee-wah-nee” is nothing new. In the diner musical number, Scott Martin was writing an homage to all these classic Broadway tunes. We actually filmed part of it that never got into the movie. Some of that is in the deleted scenes.

SW: How did you develop that musical number, where the camera keeps landing on different people, saying one word each, like “Rich” (cut) “Bitch” (cut)?

PB: Scott wrote the song and I approved it. I got the actors to record it, we had the playback tracks, and then I had to figure out how to film everything. And the editor Russ [Harnden] and I figured out a clever way to edit it. We were quite pleased with it. It was very tricky. Scott did a great job in the first place, writing the song with overlapping dialogue. I think it’s one of the catchier songs in the movie.

SW: What musicals inspired you the most?

PB: I’ve always been a fan of “West Side Story.” Originally I was trying to get George Chakiris, who played Bernardo, Natalie Wood’s brother, in the movie; he won an Oscar. He was a friend of mine and I wanted him to play Mickey O’Flynn. But ultimately he passed on it. I went a different direction with Mickey anyway, a little more comical. George would have been more serious and laid back. It would have been cool to have him in the movie, people haven’t seen him in years. And I love “Singin’ in the Rain.” Standard Hollywood musicals. I’ve never been a big fan of “Rocky Horror,” believe it or not, which a lot of people compare this to.

I wasn’t really copying anything. I wanted to make a contemporary movie with a ‘50s sensibility. The original version of “Invaders from Mars,” things like that, I love all those kinds of movies. They were pretty cheesy but there are some good ones. “The Day the Earth Stood Still,” the original “Body Snatchers”—those hold up.

The movie is not set in the ‘50s. It takes place today, but in an alternate universe. The Reggie Bannister character is more like a ‘70s character, Kate Maberly is more ‘60s. I homaged a lot of different genres. It’s very scattered and it works better if you’ve seen it more than once.

I was inspired by lots of things Brian De Palma did in “Phantom of the Paradise.” There’s a lot of homages to that film. Having Paul Williams, of course. He was supposed to play Mickey O’Flynn, but then he changed to playing the host.

SW: How’d you get Paul Williams [in clip above]?

PB: I met him at a “Phantom” screening and I asked him if he still acted and he said yes. He liked the production teaser I had, and the script. I talked him into playing the part. Then it took me a while to get the money together and by the time I did he was president of ASCAP and had no time. I talked to his manager and we found one day he was available for the talk show scene. It was my very first day back shooting, with one of my heroes. I was a little nervous but it went very well.

SW: And how’d you get an aging legend like Kevin McCarthy?

PB: I met him at a film festival called Cinecon that I’m at every year. He was a guest there and I told him I was doing a movie. That’s usually how it happens: I approach people in person and they see I’m a likable guy and serious. He waffled on it. He gave me some excuses—he did an Anthony Hopkins movie called “Slipstream.” He said yes, then no, then yes, then no, and finally yes. I would come back with an offer for a little bit more money.

I was thrilled to get Kevin on board. He was 90 years old when he did that. He said at the end it was the hardest thing he ever did. All he had to do was stand there, but that’s very tiring. He was just a real professional. And we had camera problems that day. The camera would start for 10 seconds and then shut off. We were able to get another camera body but it was an hours drive away.

These little problems happened all throughout the movie. When we did the drive-in scene, the first day was sunny and beautiful, the second day it was rainy and ultimately started to snow. And we had to stop. That was very discouraging. This was hours away from where we lived, Barstow, California, at this drive-in. That’s when we ended that segment of the film. And then six years later we went back to that drive-in. The actors are totally unchanged. When they get out of the car, that’s six years later. You’d never know it. We had makeup footage and tried to match that and the hair. And everyone luckily looked pretty much the same, and I think black and white helped.

SW: How have you attracted other name actors to your films, like in “That Little Monster” (1994)?

PB: It’s persistence. With each new film, I try to make it a little bit better, try to get it more into the mainstream. One of the tricks is to try to get a few names in there, to get you more exposure. I got Reggie Bannister, at the time he was popular. And Forrest Ackerman helped to promote it, and there was a cameo from Bob Hope. It was cool to have him in there.

SW: I know you said that “Johnny X” is no longer on Netflix. But I believe “That Little Monster” is available on the rental portion.

PB: Really? I didn’t even get paid for that. I originally wrote it as a TV episode for a half-hour show in the ‘80s called “Monsters.” And my producer connection died and this other producer was lukewarm on it. So I just made the movie myself and expanded it into an artsier version, black and white, and it was shot on Plus-X also. That was 16mm, though, not 35mm.

It was another one of a series of movies I’ve been making since I was 11 years old.

SW: Some of your early directing work, from the early 1980s, is on YouTube. But I wanted to talk a little bit about your acting work. There was a decent ‘80s film I saw you credited for called “Paradise Motel.”

PB: Oh my God, you saw that movie? [laughs]

SW: With Gary Herschberger, who’s now a priest.

PB: He’s what, a priest? The “Twin Peaks” guy?! I worked with him on a Warner Brothers show, I don’t remember the name, and almost wanted to go up to him and say “I did your first movie.” I was basically a background guy in that movie, I was very young looking and it’s shot at a high school. I had one line [at the 9minute58second point]. Someone’s showing Gary around the school, and they’re walking down the hallway, and he’s seeing these different groups of people and the guide says “Punks.” And it cuts to the two punks, and then the last thing he says is, there’s a shot of me looking right at the camera and I say, “How’s it going?” And the guy says “Assholes.”

The [director] said to me, “Your voice isn’t gonna be heard,” this was 1984, 1985, and then someone said they saw me at the drive-in, in the movie. I have a VHS of it somewhere. I was in a soap opera in 1982 but that thing disappeared, it’s little known.

SW: “Shadow of the Dragon”? [NOTE: This is, to date, one of the funniest so-bad-it’s-good movies I’ve ever seen, and I highly recommend it. Character actor and musician Bill Mills posted the film to YouTube and boasted that he overdubbed about 20 speaking parts for the movie in post-production; according to his web site, he also contributed a title song that was rejected!]

PB: That was very low budget. It was 35mm but it made “Paradise Motel” look like “Gone with the Wind.” My friend Bill Mills–I put him in “That Little Monster”–one of his friends was making that movie, and he ended up casting everyone in it, including the guy with the big jaw who died a few years ago [Robert Z’Dar]. He got me in there, I had a few lines.

SW: He told me your name was Mack in the movie, because your last name was Mack at the time.

PB: Yeah, it used to be Mack. I changed it to Bunnell. He was doing that to be clever, calling me Mack. I was born Mack but legally changed it in the early ’90s.

I became friends with Mills through telephone entertainment. Before podcasts, you could call up joke lines, entertainment numbers. I ran one of those in the early ’80s. I was very well known in the underground world. I gave Bill an opportunity to do his own line. He was an actor as a kid, in the Disney film with Fred MacMurray, “Follow Me, Boys!”

I called Bill up and asked him for a few funny lines that I put in “Johnny X.” “The juggler has balls,” he came up with that one.

SW: You have been in several films directed by cult filmmaker Mark Pirro. Which is your favorite?

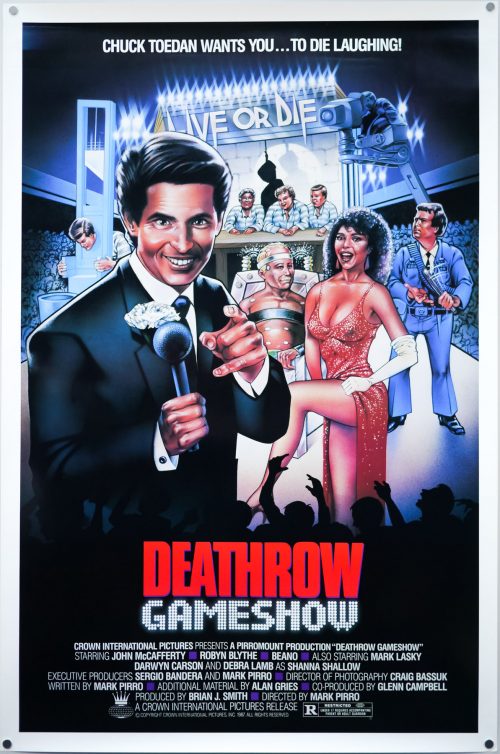

PB: “Deathrow Gameshow” (1987) is the one I met him on. I got to play a convict. Mark was a Super8 filmmaker like myself, he’s a little older than me. He’d only done Super8 up to that point. My friend told me he’d be doing the movie in 35mm, which was a big deal in 1987. It had a very small theatrical release.

It was a Crown International picture, a $200,000 budget. He made a deal with them somehow. They stayed out of the creative process.

SW: It is hard to think, tonally, of two more different films than “Johnny X” and “Deathrow Gameshow.”

PB: Mark was in his 30s when he made that movie. When I started shooting “Johnny X,” I was in my late 30s, then there was a six-year gap. But we’ve both been making movies since we were kids. We have similar backgrounds and both live in this area and made movies with our friends on the weekends.

”Deathrow” made a ton of money for Crown, when they sold the foreign rights. So they offered Mark “My Mom’s a Werewolf” (1989). Mark had written a script, Crown funded it, and he was getting ready to direct it. And the next thing you know he was fired [over salary conditions] and they got Michael Fischa. I was on the set of that movie, I was a boom operator, and I quit during the middle because I was fed up with the production. The sound guy and I were not getting along.

Mark came on the set one day, just checking it out. The guy who directed it didn’t do a very good job, did not get his style of humor. It’s just not very good. But I met Forry Ackerman [uncredited] on that set. He created the magazine Famous Monsters of Filmland and invented the term “Sci-fi.” He was in “That Little Monster,” he opens the film. I was so excited to be meeting him. Forry was walking through a convention scene, and I asked if I could please walk with him in that scene, so I have an uncredited cameo.

Speaking of Mark Pirro, I’m going to the premiere cast/crew screening in July [2017], of his film “Celluloid Soul.” I have some small, small scenes. [Note: over email, Bunnell said he has a role in Pirro’s forthcoming “The Deceased Won’t Desist.”]

I was in a few of his films, “The God Complex” (2009), “Buford’s Beach Bunnies” (1993). I have a lot of bits in “God Complex.” The guy who played God [Gust Alexander] was very funny, a very talented guy. I considered putting him in “Johnny X” but I didn’t find anything for him. He was always sweating a lot, I remember.

I think it was probably one of Mark’s best-looking productions, although I think “Rage of Innocence” (2014), that’s his best one to date, it’s a really good suspense thriller. And in the fight scene, there’s a framed poster of “Johnny X.” So I get a sort-of cameo. Mark asked for permission to do this. That was kind of cool.

SW: I heard a rumor that Tom Hanks was considered for “Buford” but his brother Jim did it.

PB: I don’t think so. Jim used a different name under the interview process, because he didn’t want to get in [based on his last name]. I never really watched the movie. It just wasn’t available. Mark showed me my scene at his place. I got a kick out of it. That was his only other 35mm feature.

Mark is now in his early 60s and he’s still making movies, so what does that tell you? He loves it, he doesn’t make any money on it. I give him credit.

SW: What is Larry Blamire’s [“Trail of the Screaming Forehead” (2007)] directing style?

PB: The best-looking films he did were “Trail,” and “Dark and Stormy Night.” The costumes were nice—my ex-wife designed some of them. I had seen his “Lost Skeleton of Cadavra” before it was released, and I just loved it, I had to meet him, so a mutual friend arranged for us to go to lunch together. And Larry was a fan of “That Little Monster.” And we became friends and he gave me some cameos in his movie. His wife Jennifer Blair was supposed to be in my movie, but she got pregnant right at that time and they were moving out of state. I’m glad I got who I got, though. She’s really good.

SW: Tell me about Ramzi Abed’s directing style.

PB: I was in “Black Dahlia,” [AKA “The Devil’s Muse” (2007)], “In a Spiral State” (2009) and “Noirland” [shot in 2010 but not released yet.] He was in Texas and contacted me and asked if he could screen “That Little Monster.” Then he came to California and got involved and he knew a lot of people that I didn’t, and he gave me some great suggestions about casting, like Will Keenan. He showed me Will’s “Tromeo and Juliet” movie, which I thought was atrocious. [laughs]

All the scenes I’ve ever done with him are improvised. I’m a ham, so I ad-lib. Lucky for him. Fred Olen Ray, with his “Bikini Airways” (2003), [my scene] was all improvised as well.

SW: Was your silly wine joke in “Spiral State” improvised?

PB: Ah yes, my scene partner said “Pinot Noir,” and I’m not a drinker, so I thought she said “Piano wire.” Ramzi thought that was really funny.

In “Noirland,” I played a funny character. It was shot in early 2010 and still hasn’t been released.

Right now, I’m mainly interested in “Johnny X” and my next movie called “Rocket Girl,” which I’m trying to get going right now.

SW: Tell me about “Rocket Girl.”

PB: It’s a fantasy about a young girl who has this adventure on Earth, in the futuristic year of 1967. I know that sounds a little weird. It’s gonna be a very cool set piece, a ‘60s vibe. It’s science fiction, a very fun movie, it’s got all my little sensibilities. It’s a more ambitious film than “Johnny X,” in a way. It’s like a stepsister to “Johnny X.” It’s not as crazy as “Johnny X,” as far as all the different characters; it really focuses on just a few characters.

I don’t know what kind of money I’m gonna put together right now. I’ve got my producer, we’ve got some money available to us, we’re gonna try to get some investors to kick in. And I can’t do the movie unless a few name actors are in there.

SW: What do you do for work in between gigs?

PB: I sold a car, I’ve been using a friend’s car. My car was seen in the Netflix Paul Reubens special. I gave him a copy of “Johnny X,” I’ve known him a few years. I just worked on a show with Alicia Silverstone, I worked on a Seth Rogen film called “Futureman.” Just for a paycheck. And I do post-production work too. I got the divorce last year. I just sold my house in Burbank. I’ve been living out of my suitcase the past year [2017].

SW: In the meantime, what is your ultimate goal for “Johnny X”?

PB: I want it to have a fan base. Unfortunately, the movie is sort of buried. Not that many people know about it. It’s never been super well-promoted. We had no advertising budget whenever we’d screen it. It was a word-of-mouth type thing. I predict it will find a fan base, that this movie has a destiny. Ultimately, beyond people discovering it, I want to get it broadcast on cable TV, and also released on Blu-Ray. And on the Criterion Collection.