New York City run, June 19, 1992. No one is credited for the blurb.

In 2016, I began a column on this blog called “New York Times Slights,” in honor of filmmakers who were fortunate enough to see their movie play in New York City theaters, only to be faced with a vague, dismissive pan on opening day.

The late Vincent Canby, the Times‘ chief film critic from 1968 to 1994, wrote the most notoriously terse negative reviews. He’d take the time to include one or two disparaging adjectives (“inept,” “terrible,” “unfunny,” “witless,” etc.), the briefest of plot or–if he was reviewing a comedy–joke descriptions, and then a blasé metric such as “the direction is as amateurish as the acting.” No further explanation as to why he considered the movie so bad was worth expending precious energy on.

Andrew Yates’ “Life on the Edge,” a farce about an earthquake that ruins an already-chaotic Hollywood Hills party, played New York City’s artsy Quad Theater for a week in June 1992. Canby’s sparse takedown made headlines as far away as Sydney, Australia, where a journalist marveled at its brevity (90 words!)

Over at The Daily News, critic Harry Haun, while scathing in his response, devoted eight paragraphs to discussing the film; Variety’s Lawrence Cohn divulged several plot twists in his more even-handed, but generally unfavorable 11-paragraph review.

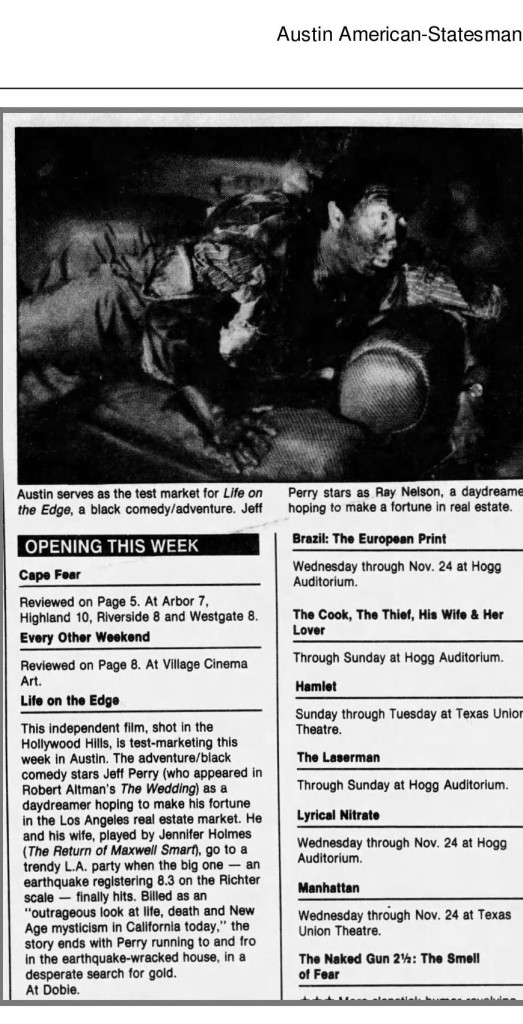

Seven months earlier, in November 1991, the film was released, also for a week-long run, at the similarly artsy Dobie Theater on the University of Texas at Austin campus, where Richard Linklater’s “Slacker” had made waves only a year earlier. Marjorie Baumgarten, reviewing for The Austin Chronicle, called “Life on the Edge” “one of the worst movies I have ever in my life seen” and granted it a BOMB! rating. Her pull-no-punches diatribe amounted to just over 300 words. (The Austin-American Statesman didn’t include a review, opting for a simple film summary):

Canby’s particular method of panning, on the other hand, speaks volumes in what it doesn’t bother saying. While a statement like “worst movie I’ve ever seen” has enough ardor behind it to lure specific viewers–like me, who love “so-bad-they’re-good” movies–Canby can’t be bothered to express any emotion, beyond indifference. “If you care for such gags, help yourself,” he seems to be scoffing, “but this is beneath me. It barely warrants a response.”

Naturally, Canby rarely if ever snubbed a film to this degree if it had any big stars or major directors or heft behind it. Suppose, for instance, if Canby also despised “Batman Returns,” which opened the same day as “Life on the Edge.” He’d excoriate the film, no question, but in a more thorough way. He’d tell you why the movie’s elements, from direction to acting to art design to lighting, didn’t add up, why it was such a disappointment–why it mattered–that big-name talents like these couldn’t collectively generate a good film. The readers would expect no less of an effort.

For a “little” film like “Life on the Edge,” though, how many people were going to see the film anyway? Who’s heard of it? Who the hell is in it, who directed it? Today, for better or worse, simple aggregated scores on Rotten Tomatoes help viewers decide which films to see, at least the ones they weren’t automatically going to see, regardless of the critical reception. But back in the olden days of 1992, it mattered to fans of arthouse cinemas like Quad and Dobie what the chief Times critic thought of an independent movie. His enthusiasm or lack of it could sway them to the theater or keep them at home. A movie like this, with no stars (at least at the time–lead actor and Steppenwolf Theatre founder/regular Jeff Perry eventually gained fame for a prominent role on TV’s “Scandal”) absolutely needed a positive review to get asses in seats. So a review like Canby’s, unless it piqued the interest of film masochists like myself, could only hurt.

And it did. As stated before, in both Austin and New York, the movie lasted only a week, disappearing without a trace. (I’m apparently not the only one curious about what happened to it: check out Mike Justice’s entry on his excellent movie detective web site, A Scream in the Streets.)

The movie, previously titled “The Big One,” never received a VHS or DVD release. In fact, for that reason alone, I was considering placing “Life on the Edge” in another Hidden Films category, that of “They Ought To Be on DVD,” concerning films that get a theatrical run but no ancillary market distribution. But a) in this case, the Times review was so glaringly curt that the film fits more snugly into the “Slights” category and b) after watching the film, while I would totally support a DVD release, I’m not sure it ought to be on DVD. It will be most of interest to those wondering how a young Jeff Perry carried a film; “Life on the Edge” was his first lead movie role.

It did not even appear on late-night cable (there is a rather explicit lesbian sex scene and a racy post-coital sequence, with just enough skin on display to place the film into the screwball-sex-comedy-on-Skinemax genre). Most peculiarly, though, the film does boast a TV Guide review that called it “amusing if predictable”; the review, which spoils the entire plot, does not have a publication date nor byline, and no one I contacted who worked at TV Guide back then had any recollection as to why the magazine covered the film or where they viewed it, let alone who wrote the piece. [NOTE: Upon further research, I realized the review, by Leonard Rubenstein, was culled from “The Motion Picture Guide: 1993 annual (The Films of 1992).“]

Also weirdly, TV Guide is the only site to identify 1988 as “Life on the Edge’s” release date. That happens to be the year the film was shot, but it was not shown publicly until April 1990, when it was selected for screening at the Houston International Film Festival (later known as WorldFest) and received no theatrical showings until the 1991 Austin release.

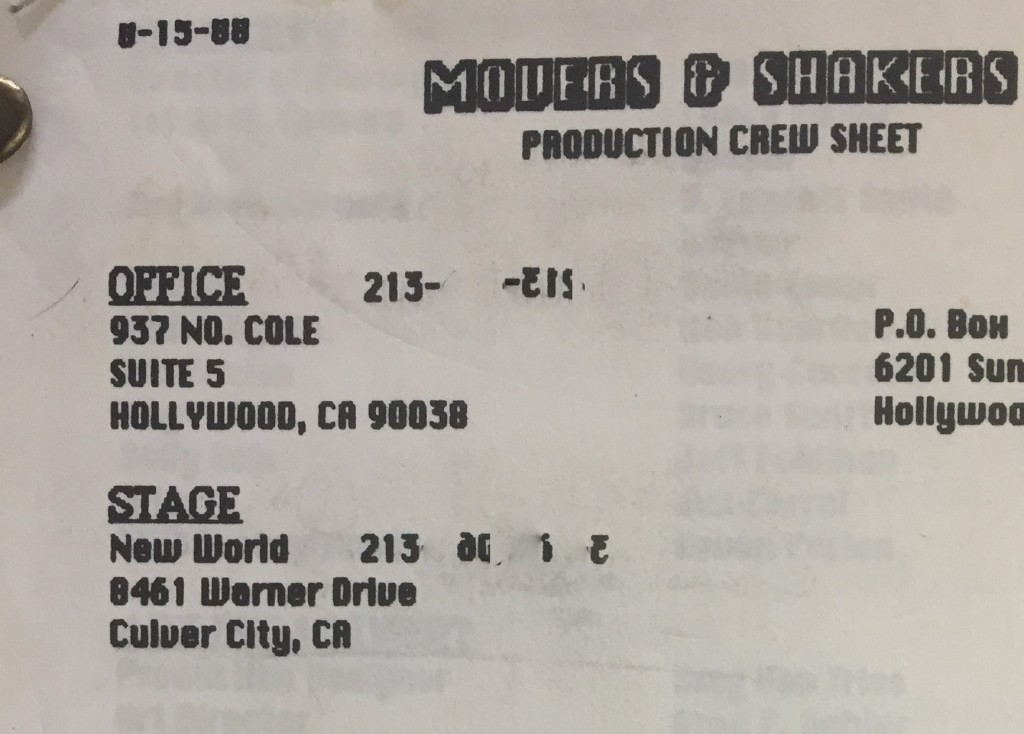

“Movers & Shakers” was Yates’ entity through which he handled and distributed “The Big One”/”Life on the Edge”; it’s listed on the aforementioned call sheets and newspaper ads. But, in the Austin American-Statesman ad for the film, Cabriolet Films, a small outfit out of New York that distributed several films theatrically during the early to mid 1990s, is also mentioned.

No one affiliated with Cabriolet that I reached out to recalled the film, and none of the actors interviewed said they were present at this Austin screening, despite the ad’s assurance. (I was only able to speak briefly with Jeff Perry, who said he hardly remembered the whole experience, and with actor Andrew Prine, who said more or less the same thing, and whose wife Heather assured me he was not at the Austin event). Yates, with whom I exchanged a few emails, didn’t respond to questions about the movie’s screening history. So it’s left to the sands of time how Cabriolet got their name on the picture, and why a cast and director in-attendance showing was promised.

Just for kicks, here’s the full ad, which has the best tagline of all time (especially considering the film is not, in any way, about harassment):

A former owner of the Dobie had held on to materials confirming that Cabriolet rented the theater for the Austin showing, a process known as “four-walling,” in which distributors pay to play their film so that it can be reviewed by local papers. My hunch is that Yates repeated this process for the Quad showing, but I could not confirm this from Yates, nor from current or prior managers of the Quad.

What I could confirm about the history of “Life on the Edge,” from producer Eric Lewald, screenwriter Mark Edward Edens, and assorted cast and crew members, was none too happy. (Considerably happier: Edens’ recent short novel, “Death Be Not Pwned,” is totally worth purchasing in Kindle or paperback form, on Amazon. It’s a clever, gory tale about an aspiring collegian, already plagued with job, girl and application essay woes, who undergoes a hit-and-run with–literally–Death, and is obligated to chauffeur the Grim Reaper to various gruesome appointments).

During his undergraduate years–1972-1976–at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville, Lewald, a film studies major, worked on a committee that selected and screened movies for students. “There were no video stores at the time, so if you wanted to see an interesting movie, or cult movie, you had to see it on campus,” he said. “We booked about 180 movies a year and you got to see them all free.” Edens worked on the same committee.

Lewald spent a semester at NYU’s film program, because “they didn’t have much in the way of film classes at UT,” and that’s where he first met Andrew Yates, whose family ran–and still runs–a lucrative construction business in Mississippi. Lewald, a Tennessee native, bonded with his fellow fish-out-of-water, or as he put it, “We were kind of thrown together and a friendship started.”

In the fall of 1976, a full year before “National Lampoon’s Animal House” went into production, Lewald and his UT buddy Glenn Morgan began directing a raunchy but overall gentle sex comedy called “Incoming Freshmen,” which they also wrote. Yates came to Knoxville to do sound work on the picture, but, as Lewald recalled, “He got mononucleosis, so someone had to take over.”

The loosely-plotted film tracks the gradual blossoming of a naive, virginal college freshman (the late Mary Moon), as she’s taken under the wing of her promiscuous yet good-natured roommate (the late Leslie Blalock). The cast was predominantly students, with a few cameos from actual UT professors, as well as Lewald and Morgan themselves (playing a lecherous suitor and a lecherous professor, respectively). Local TV personality Carl Warner–later a constable, now retired–plays a poly-sci prof who fantasizes about some of the comelier co-eds mid-lecture. High-jinks include a beachside chalet party, a peeping tom session, a cheery sorority pledge meeting with a hilarious re-enactment of “Little Red Riding Hood,” and an even funnier self-actualization seminar. There is a peppering of T&A–the filmmakers admitted they were targeting late-night drive-ins as far as initial screening venues–but nothing too graphic.

In a recent email to me, Morgan said the principal photography budget came out to around $13,000 and pick-up shots cost an additional $8,000. In 1978, the notoriously sleazy Cannon Group–a year or so before the Israeli cousins Menahem Golan and Yoram Globus took over/catapulted the studio–ended up paying the boys $10,000 up front to distribute the film. Before they did, they chopped up much of Lewald and Morgan’s footage, and director Joseph Zito was recruited to shoot additional scenes, with heaps more gratuitous nudity (Warner’s prof was replaced with a fat, drooling prof who now pictures his female students buck naked, for instance) and New York actors attempting Southern accents. The film played drive-ins and subsequently indoor theaters in 1979, but it was another two years before Lewald and Morgan received any more money from Cannon–about $3,500 in foreign sales, according to Morgan.

They have yet to receive any more proceeds, making them just two of thousands of filmmakers hornswoggled by Cannon. But the film has enjoyed enough cult appeal for Lewald and Morgan’s original version to be screened every so often (for a more in-depth profile of “Incoming Freshmen,” check out this fascinating Fred’s Garage article from 2012, an extension/re-edit of a 1999 article in former Knoxville weekly Metro Pulse.)

Meanwhile, back in Mississippi, Yates had completed a documentary called “Class of ’64,” about the 1964 murders of civil rights workers Michael Schwerner, Andrew Goodman, and James Chaney in Philadelphia, Mississippi.

“Andy grew up in Philadelphia, he was 13 when all that happened, and it really burned itself into his memory and he felt he had to make a movie about it,” said Lewald. “I thought he really did a nice job of it. He showed it to some black churches and he got quite an ovation. I don’t think it was ever screened commercially.” [NOTE: the documentary was cited in Charles M. Dollar’s 2015 essay, “Florence Latimer Mars: A Courageous Voice Against Racial Injustice in Neshoba County, Mississippi (1923-2006),” as: “Andrew Yates, “Class of 64,” (Los Angeles: Unpublished Historical Documentary Video, 1974). Copy in possession of the author.“]

In 1978, Yates expressed a desire to shoot his own narrative feature, which Lewald described as a character-driven drama set at a computer science school. “I helped him get a cast and crew together, throughout Louisiana and Mississippi. We shot all that summer, and it just wasn’t holding together. The movie shut down before he had something he could cut together. It was very tough on everybody. I felt awful, I felt I let him down. We’d had our movie and it sold and we felt we could do this for Andy, and maybe he got a little too ambitious. He shot in 35mm instead of 16mm, which we had. And he wasn’t nearly as confident as a writer as Glenn Morgan and I were with ‘Incoming Freshmen.’ It was a simple character-driven comedy, and we kept it as simple as possible because we knew we weren’t experienced, and it worked for that reason. Character dramas are hard for [even] experienced writers to get right. And I think Andy never quite knew what the story was. As we shot more scenes, that became more evident.”

“Andy had hired some low-end professional crew that knew what they were doing, and didn’t like [the film],” Morgan said. “The secret to ‘Incoming Freshmen’ was that no one knew what they were doing, but everyone was treated with respect, and we all got along. But whatever the mix was in Mississippi, it was not good.” Lewald said he and Yates didn’t talk all that much for the next decade.

Two years later, Lewald and Edens were called to New York by none other than Joseph Zito, who’d mucked up their first film, to do a complete re-write on a horror outing he was directing, called “The Prowler.”

“We stayed at this hotel off Times Square, back when Times Square was still seedy,” Edens remembered. “We’d type pages all day on my manual typewriter, and then take them at night over to [Zito].”

“There’s things in it that don’t make sense, because of the lack of visuals,” he continued. “The first murder is supposed to take place right after WWII. A soldier comes home and his girl is cheating and he kills the guy. So [in the script], he had all this military stuff on. He’s wearing a gas mask as a disguise, killing people with bayonets. But for some reason [in the film], he’s using a pitchfork!”

“Our proudest moment was, we had this ‘Psycho’ [reference], where a woman is in a shower, she thinks her boyfriend is coming in, but in fact he’s been killed. We had it written in the script, I don’t know if it made it in, where you see the shadow of what looks like a large erection on the shower door, and then the door slides open and it’s a bayonet. We were trying to mix up sex and horror, and Joe was saying ‘No, no. Horror movie audiences don’t like sex in there.'”[NOTE: two years later, Zito made “Friday the 13th: The Final Chapter.”]

In a coincidence that could serve as the plot of another horror film, Lewald landed his first industry job in late 1984 at animation giant Hanna-Barbera, and bumped into Neal Barbera, son of co-founder Joseph Barbera, and original scribe of–yep, you guessed it–“The Prowler!” (“There was of course an awkward moment, like, ‘Oh, you’re the guy who rewrote our movie!’ But he was a nice guy. His dad was really a character.”)

“From early 1985 on, I was working steadily [in Los Angeles] in animation, and almost immediately I brought Mark out,” said Lewald. “And then Andy came out, maybe in 1987. By then, Mark and I had really established careers out here. I was a few months into a staff position at Walt Disney, when Andy got the money together [from his family] to try to get a movie made. I asked Disney for a six-month leave of absence to help my buddy, and it was amazing: they said yes. They extended my contract.”

“Andy wanted Eric to be involved as producer, and I offered to write the script for him,” said Edens. “It was written really quickly, right before we went into production.”

The loose plot involves the following individuals trapped at an elevated hillside Hollywood house party during a colossal earthquake: the rather timid, passive “hero” (Jeff Perry), a frazzled real-estate agent trying to land a lucrative deal, not only to pay off two thuggish loan sharks (Curtis Taylor and Roger Callard) but to save his relationship with ever-distant wife Jennifer Holmes; a plastic surgeon (character actor Andrew Prine, who played the lead in several cult 1970s horror films), owner of the gaudy monstrosity where the party is held, who is having an affair with Holmes; his trophy wife (Greta Blackburn), who spends much of the party lusting after Perry; an arrogant hack writer (Tom Henschel), most known for a dreadful sitcom called “Here’s Spunky!”; a New Agey mystic (Jennifer Edwards, daughter of Blake) who entices the guests to embrace the new trend of “skywalking,” or bungee jumping; an embittered anchorwoman (Kat Sawyer-Young) who ends up in a lesbian dalliance with velvet-voiced, Laurie Anderson-esque performance artist Liz Sagal (sister of Katey Sagal from “Married… with Children”); two missionaries (Ken Stoddard and Michael Tulin), one of whom is a closeted homosexual; a bulimic (Denny Dillon of the hilarious 1990s HBO series “Dream On” as well as the ill-fated sixth season of “Saturday Night Live”); a militant survivalist (the late Thalmus Rasulala), and a habitual cocaine user (Martine Beswicke, a model/actress honored with two James Bond film roles, in “From Russia with Love” and “Thunderball.”)

Sagal’s Laurie Anderson impression is spot-on, as is Edwards’ sweet, sunny take on the hippie guru; there is one truly dark joke that elicits a chuckle (the child actress playing the titular Spunky sitcom role is crushed to death by a felled building, with her little feet sticking out, Wicked Witch of the East-style); and the scene in which the ululations from the lesbian encounter overlap with the screams of pain from a neighboring childbirth is impressively edited.

But most of the humor is in the slapstick vein. The entire second half of the 70-minute picture follows Perry, who’s desperate for cash and who’s learned that Prine has a stash of gold hidden somewhere in the house, bumbling from room to room, hiding under beds, bathroom cabinets and desks, slamming into doors and falling into pools as he searches for the treasure. Occasionally, a lame double-entendre pops up: while Perry searches for the gold in the closet, he’s interrupted by the aforementioned homosexual, who goes into a long monologue, steeling himself to come out; exasperated, Perry eventually shouts: “Get the fuck out of the closet!” The homosexual thinks that voice came from God and, indeed, announces his secret to the party guests, who couldn’t care less. After all, there’s a huge earthquake and the world–or at least Los Angeles–appears to be ending.

Transplanted from Tennessee, Edens was particularly amused with the kooky mid-80s Hollywood show-biz types he’d met.

“It was a reaction to what Hollywood and Los Angeles was at the time, the type of people you’d run into, the Laurie Anderson-type performance artist, and the low-rent Jane Fonda and Tom Hayden. And the bad sitcom writer was like every writer you’d run into in L.A. They always wanted to write the great novel but they’re writing for something like ‘Here’s Spunky!'”

Yates, equally out of his element in Hollywood, was a “real libertarian-type guy,” said Edens. “I think all the social satire making fun of the Hollywood types really appealed to him. That was one reason I put that in there. I thought he’d find it funny.”

But by the time the script was finished, Edens had doubts that Yates could pull off the job, and did not want Yates to waste his family’s money on it.

“Andy liked comedy, he’s got a sense of humor, but he doesn’t really understand how to be funny, or make something funny,” said Edens. “So before he went into production, I tried to talk him out of doing it. It had gotten too complicated. The idea started out much smaller, but often when you start writing something, you think, ‘It would be funny if this guy was there, and that guy was there,’ and it just got bigger and bigger. And I realized, for your first movie, if you’re doing a low-budget movie, it should be something simpler. I said, ‘What you really should do is ‘My Dinner with Andy.’ Two characters at a table. And then do something more complicated later.'”

“I had written a little script about a guy who comes into town and his buddy gets kidnapped by someone he owes money to, and I was trying to talk him into something like that,” Edens continued. “It’s not like a comedy, where it’s really easy to fall flat. But he kind of had his mind set up, so I couldn’t talk him out of it.”

Jean Childs, who cast the film, remembered that Bill Maher read for Perry’s part.

“My sense was that Bill really didn’t want to do it, that his agent made him go,” she said. “It wasn’t his kind of comedy. I didn’t sense great enthusiasm.”

“Jeff was fairly fresh, he was up against people with a lot bigger names,” she added. “I think the comedic actors with names were out of our range. It certainly wasn’t a large budget. The producers were brand new but were caring and diligent and worked hard to find a good cast. Eric Lewald was a dear.”

“Jeff Perry was a really good actor, he just didn’t have the leading man’s look,” said Edens. “He was like Steve Buscemi—a little funny-looking.”

It was Jesse Long, a script supervisor and college buddy of Lewald and Morgan’s who served as key grip on “Incoming Freshmen,” who suggested Jennifer Edwards for “The Big One.”

“I’d worked on a film called ‘The Perfect Match’ with her in 1987 and we’d become real good friends, so when Eric and Mark approached me about ‘The Big One,’ I thought of her. I got her involved.”

“Jeff and I were the only two people cast at the beginning,” said Edwards. “I remember sitting with Andy, and they didn’t have a full screenplay at the time. They told me the basic concept. I thought it was really funny. I’d never played a channeler or a psychic or anything like that. And we basically shook hands and they said, ‘We’ll see you in a few weeks.'”

Long, by then an indie film veteran, recommended a lot of crew members as well, many of whom had worked on Roger Corman productions. He himself was supposed to work on the film, but got assigned at the last minute to “Pet Sematary” up in Maine. He ended up with an associate producer credit on “The Big One”/”Life on the Edge.” (Earlier that year, he’d worked on a nutty, underrated sci-fi comedy called “Meet the Hollowheads,” featuring a then-unknown Juliette Lewis, that, coincidentally, had the original title of “Life on the Edge!”)

Jennifer Holmes wrote her scant recollections of joining the cast, whom she got along well with, via email: “I think we were all just making a little money with zero expectations of the film doing much. I recall my agent mentioning that they were going to have a theatrical release, but the script and actual scenes didn’t convince me of that expectation. The script was not particularly well-written, more like a low-budget overseas script. I was grateful to be on a set–any set–enjoying work, especially with two [young] kids at home.”

“I wasn’t too fond of the casting of [Holmes],” said Edens. “I just thought that actress came off sort of cold. Of course she’s angry at her husband and has a reason to be cold, but you’re still supposed to like her. I thought someone like Jennifer Edwards might have been better. She was really funny.”

“I thought the actors that played the newspeople were really funny,” he continued. “Thalmus Rasulala, who played the survivalist, had been in ‘Blacula,’ and William Marshall, who actually played Blacula, came and read for that part. He was a terrific actor, with a great presence, but by that point, they thought he was too old for the part. He seemed a little frail.”

Denny Dillon was the first cast member to inform me, over email, that the film was shot during the Los Angeles writers’ strike, which she believed was the reason “so many actors were available.”

“I feel like we all did it for the same reason—that there wasn’t any work around,” Dillon said during a later phone interview. “The script was OK initially, the idea that all these people [get together] and there’s an earthquake and everyone changes, and they do the worst thing [possible.] Like, I’m trying to diet, and then I eat too much, and—what can I say? It was a terrible experience. Not with the actors. We all banded together like children that know they’re in a dysfunctional situation. It’s very hard when the person at the helm doesn’t seem to be accomplished. That’s basically all I wanna say about it. I can’t even remember his name. I just sort of tried to get it out of my mind. You win some, you lose some.”

Martine Beswicke shared Dillon’s horror with the whole experience and–like many cast and crew members interviewed–also forgot Andrew Yates’ name.

“It’s an appalling film,” she burst out laughing. “For me, it’s the worst film ever.”

“Let me tell you something. All of us—we were jobbing actors and we all had some kind of a name, and we were all out of work. So when this came along, we thought, ‘Oh, what the hell, let’s do it.’ We knew it was a crap film, but we didn’t realize to what extent, until the day we all arrived at this set [at a Culver City warehouse, where the interiors were shot]. The director arrived in a limo on his first day! As far as we were concerned, that spelled absolute rubbish. This is someone who’s never directed before! The writing was on the wall. All of us kind of knew that this was not gonna be our best work. We weren’t going to be proud of it.”

Limos aside, another of Yates’ quirks, as Lewald recalled, was his needing to refer to a thick book of notes–“like 400 pages”–on how to get emotional reactions out of the actors.

“He’d gone through Mark’s script and [written], ‘This line means that she’s unhappy with him. This line means he’s responding to her and not quite understanding why she’s that way.’ They’d run a scene and the actors would say, ‘Is that OK?’ and Andy would have to check his book. He lacked the dramatic instinct, he lacked the storyteller’s instinct, just the sense of interacting with the cast and saying, ‘Oh, wait a minute, she needs an extra moment here to glare at him,’ or ‘She’s not responding strongly enough.’ He just was not getting it.”

“One of the actors pulled me aside, I don’t remember which one, a couple of weeks in,” Lewald continued. “We’d maybe shot a quarter of the scenes. And they said, ‘I’m worried about Andy, can you talk to him? I’m an experienced actor and we all signed in because we like Mark’s script so much, but we’re not getting any direction out there. I can protect my performance, but things seem to be drifting.’ And by that time, I kind of sensed that he had become overwhelmed, and I had to look the actor in the eye and say, ‘I’ll try. But honestly, protect your performance, self-direct, [because] I don’t know if there’s anything I can do to improve the situation.’ And that’s a daunting thing to tell an actor. It was depressing and anxiety-causing for me, because we had this big cast and crew and everyone’s working overtime to try to make a half-million dollar movie look like a three-million dollar movie. And I just had this sense that Andy wouldn’t be able to handle it, just like the one in 1978 that fell apart.”

“I was watching him spend his inheritance at the same time [he was struggling]. I was really concerned for him. I really wanted to make this work for Andy. If he failed, he wouldn’t get a chance to do this [again], ever.”

Lewald added that he mostly stayed away from the set, and, due to stress, lost roughly 20 pounds during the experience, but in his mind, that was a rare high point.

Edens also avoided the set, but unfortunately his wife, production designer Amy Van Tries, was there the entire time.

“Andy just shot the script, he didn’t have any flexibility,” she remembered. “It got progressively worse. Andy started to hide from people.” Since some of the actors, like Prine, were seasoned professionals, “they knew more about certain aspects than he did, and that made him insecure.”

Not everyone had such a terrible time, however. Actor Vaughan Armstrong said, “The more [directors] leave me alone, the more I like it.” (Not that he had a blast, either: he, like several others interviewed, admitted to me that, until my phone call, he’d forgotten he’d done it!)

Greta Blackburn acknowledged Yates’ lack of experience, but said that nonetheless meant he listened to suggestions from her and other cast members. She also said working with Jeff Perry was great fun, as did others interviewed who knew and respected his theatrical work. (Conversely, Tom Henschel recalled getting frustrated with how long it took Perry to prepare for scenes, given his method acting/theatrical background.)

Most of the interviewees, whether or not they had a pleasant time with Yates, could scarcely remember him.

“I couldn’t pick him out in a lineup,” said Michael Tulin, who now does mortgage lending but still acts in the occasional play. He remembered the shoot as “funky and fun.”

“He was not very tall and he had a reddish beard and I can picture him sort of walking around in this not very commanding way,” said script supervisor Rachel Atkinson.

“He was a quiet, intense kind of guy, bald and bearded, not that friendly, kind of a sour look on his face,” recalled production coordinator Steve Lustgarten, who recently directed the horror film “American Scarecrow.”

“Reserved” was the most commonly used adjective about Yates. Other adjectives that came up were “mousy,” “pouty,” “quiet,” “non-communicative” and “overwhelmed.” Several agreed that he deferred to the actors, cinematographers and assistant directors at many points, when it came to decisions.

Generally, people’s most vivid memories of the shoot involved behind-the-scenes incidents. Blackburn, for example, recalled posing naked for her character’s Plaster of Paris bust–a prop she still wants returned to her.

“My face [on the bust] clearly is very unhappy,” she said. “I was doing everything I could not to go, ‘Ugh, I hate this.'”

Edwards underwent a far more traumatic ordeal–a miscarriage!

“By the time we were ready to shoot, I was 16 1/2 weeks pregnant, and I didn’t tell anyone but the costume people. I knew I was gonna be needing some adjustments. One day during lunch I went to the restroom and I was bleeding, and I told the director and he said ‘Do whatever you need to do.’ We had shot like three weeks. I came back and finished, I think I had another week of shooting. That was a weird time for me. I went on to have another baby in 1992. I have two children.”

Later on, Edwards underwent a minor injury during an Uzi shoot-em-up sequence. “The special effects [guys] put all the blanks and the caps on the wall, and I accidentally got shot in the ass, with one of the caps. It wasn’t horrible, but I did have a burn mark on my butt for a few weeks. It wasn’t the most professional set that I’ve been on.”

Many cast and crew members recalled the super-long hours and dog-days-of-summer temperatures. Armstrong remembered the “communal dressing area, a large room, and a couple of us had mattresses on the floor if we wanted to take a rest.”

Second assistant director Tom Koel remembered a three-hour, late-night hunt to kill a pesky cricket, hiding way up in the high beams. Art director Greg Oehler remembered waving a pipe at a would-be burglar, who’d broken into the warehouse bathroom. Oehler also chuckled over the shoddy special effects.

“You had a shaky cam, you had holes drilled in the set and things tied around speakers and shelves and whatever you could find, and as many P.As as you could find shaking things. I remember being on the roof boring a bunch of holes, and I put drywall compound up there and then shifted the cracks so dust would fall. It was hilarious.”

During the big earthquake scene, Kat Sawyer-Young is supposed to be having sex with Liz Sagal, and, she said, “I remember having to pretend like the whole [bed] was shaking. I was a little uncomfortable shooting that scene.”

Another technical hurdle was that the scenes were, as Lewald and others recalled, taking too long to light. As a result, the film went over budget.

“We were running out of money about three-quarters of the way through,” said Lewald. “And Andy’s brother Bill came by and said, ‘Look, we gotta tighten things up, speed things up. Do we know someone that can light more quickly?'” Hence, director of photography Tom Fraser was replaced by Nicholas von Sternberg, son of director Josef von Sternberg. “He’d throw up a couple of lights and say ‘Go!’ and he worked about twice as fast.” (Sternberg said he remembered virtually nothing from the shoot, except that the cast seemed antsy. Fraser, reached by email, also said he barely remembered the movie, except that it went over schedule and he was obliged to start work on another film.)

“I liked Tom Fraser a lot, but he wasn’t fast,” said Oehler. “I took a photo of a 3K light, with like 15 cutters [to block the light] around it. It was the funniest thing I ever saw, I’ve never seen so much done to a tiny little light!”

Bill Yates put in a little extra money and “helped with organization and facilities. It was what was needed to get us through the end,” said Lewald.

Except that the film didn’t “end” for a long time after the shoot ended.

Michelle Pazer, one of a team of sound editors doing post-production work on “The Big One,” said, “I spent a good three-quarters of a year in post with Andy. I know we worked on it into the summer of 1989. I remember working 20-hour days just to get 10 mixes. His tenacity–he would just drive everyone crazy. He was just certain it was gonna be his break. I just felt really badly for him.”

The schlocky special effects continued in post. Pazer said she and the others cracked leather, for instance, to simulate the earthquake.

Glenn Morgan, who was friends with both Lewald and Yates, rented an editors’ room out to this crew, in the same building where he did his own editing work. He also recommended and hired crackerjack editor Armen Minasian for the film. Minasian, sadly, was in poor health by the time I reached out to him; his wife, Linda, remembered “The Big One” being a laborious experience overall for Minasian.

At some point during the editing process, Lewald and Edens, expecting a roughly 100-minute film, were presented with a 70-minute cut. Edens was particularly furious.

“What really made me mad was the way he cut the ending. It was supposed to be kind of sweet and happy, where the estranged married couple trapped in the fallout shelter [after the apocalypse] have to spend a month getting to know each other again, and they’re gonna solve their problems and get back together. But he made it look like one of those ‘Ha, ha, everybody dies’ endings, which I thought was dark and grim and miserable. I got really mad at him. So it went back to the original.”

“Mark and I had sat through a lot of the early rushes, and we were laughing a lot,” said Lewald. “There were some nice production values and we thought the actors were doing fine. We were getting what was funny about the characters. And then that first screening was quite a shock.”

“He cut out a lot of what Mark thought was funny or important in the writing. He may have kept most of the [dialogue] in there, but it just felt like he moved the scenes as fast as possible. I didn’t see humanity in the characters. It wasn’t funny or mysterious. I think he kept on watching these scenes and not getting why certain characters were doing what they were doing, so he cut it down to the bare [minimum], just moving the plot forward. He thought the character stuff was weighing the story down.”

“I said, ‘I hate to say this to you, and I may not be much of a producer, and I know how much wanting to be a moviemaker means to you, it’s all we talked about in college. But I just think you’re ill-suited for it. You’re just gonna make yourself and the people around you miserable if you keep trying to do this. Take some time off. Reflect. Find another way to contribute to making movies. But being the auteur, the writer/director/editor of movies, is not something that you seem cut out for.’ And that was the last he spoke to me. That’s not an easy thing to tell someone, especially if they’re a friend.”

Before I get into what happened to “The Big One”/”Life on the Edge” after that sad day, I must thank Mark Edward Edens for sending me his VHS copy of the film, which was still called “The Big One” and had a 1990 copyright date. He also sent me the original script, which did more or less match all the dialogue on the screen, but I agreed: many of the characters’ interactions/facial reactions seemed alternately stiff and cut short. (“When I show it to people, I always stop it, and say, ‘Here’s what’s supposed to be happening here,'” said Edens).

As for Yates, I never got to interview him, but after I sent several emails, he responded with a Vimeo link to his final version of the film, now called “Life on the Edge.” It had four copyright dates in the credits–the last two were 1996 and 1999. And other than some rescoring here and there, the only changes were some slapstick bits involving caterers goofing off at the party (in footage filmed with new actors, sometime during the mid-90s, after the film’s theatrical run) and some exterior shots of houses and beaches. The link was only valid for a few days before expiring.

When I reached out to Yates again to speak about his experiences on the film, his response, via email, was: “That film was shot over 30 years ago. Eric Lewald and I had become friends at NYU but the friendship ended after that film. I’m not going to comment on their [Edens and Lewald’s] writing or producing skills. I haven’t had contact with these people in 30 years.” He also expressed bafflement as to why I was so interested in the film; my response–that I have a strange fascination with films that play theaters and then disappear entirely, as there’s usually a good story behind them–did not yield a reply.

I spoke to a few of the newer cast and crew members, whose memories were also scant because, they said, the ’90s shoots were so short.

“It was only two or three days of work,” said Robert Heaster, who plays one of the caterers. “I had friends with little parts, so it was light and fun. He wasn’t happy with the film, and he opened it up to a group of L.A. actors and improvisors to audition for parts. He was going for that Peter Sellers vibe, like ‘The Party.’ It felt like it was the only thing he ever did and he wasn’t gonna rest until there was something more that he wanted out of it.”

Actress Mira Wilder said her neighbor at the time was line producer Alessa Carlino, who brought Andy to Wilder’s improv class. The shoot, she remembered, was in Ojai, in a big dining room area of a mansion-sized house. She worked about one day on the picture, with no script to go on, just “in-the-moment shooting. We’re serving [food] in the kitchen and we have to act as if everything is swaying and moving.” Neither she nor Heaster ever saw the completed version, nor heard anything more about it.

Composer Mike Garson, who has performed with David Bowie and Smashing Pumpkins, among many other acts, was hired to score both “The Big One” and the later reshoots.

“I think it opened in the Village and it was a very fast run,” he recalled. “Andy was in shock he didn’t do everything [right] the first time, so he thought maybe he could do it better, maybe the music could be better. I remember making it sound like those “Pink Panther” movies, where they’re sneaking around. I’m playing panflutes and bass parts and stuff. You get very nonjudgmental if you’re sitting with a film every day and you’re writing to it. Even if it’s horrible, you’ll find something horrible to play. Or comical.”

Like many others interviewed, Garson said he wanted Yates to find some success, “at least get it out on VHS or DVD.”

To my knowledge, no further attempt has been made to release the film. It’s been established that the film is far from great, but I believe its stellar cast of character actors, as well as its potential for cult appeal, warrants a small DVD release. As I wrote earlier, I’m not the only one (though I may be one of the only ones) who wondered what happened to it.

Meanwhile, let us hope that the third entry in the “New York Times Slights” series is a sunnier affair!

And stay tuned for a few stand-alone interviews I did with some “Life on the Edge” cast members, reflecting on some of their other obscure/under-the-radar films!