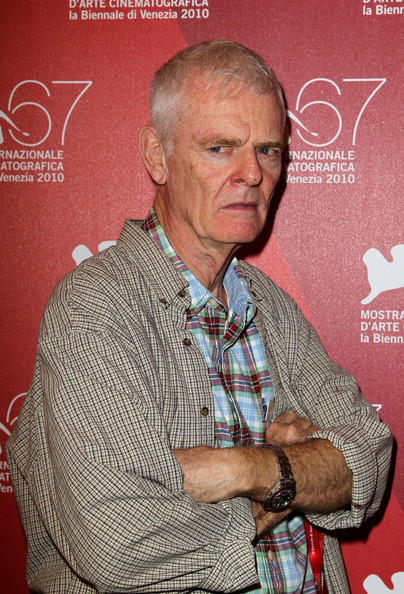

As noted in my interview a few months ago with Paul Morrissey, the 74 year-old director hates any cinematic style that purports to be “underground,” even though his self-financed, bare-bones films (especially the ones he made during his term at the Warhol Factory) often play out that way. He misses the “classic” Hollywood studio dramas of the 1950s (like “On the Waterfront”) and despises the grisliness of contemporary dramas, many of which bore rigorously, with utmost seriousness, into topics like drug addiction and other forms of degradation.

Ironically, Morrissey’s most well-regarded films (the “Flesh”/”Trash”/”Heat” trilogy, “Women in Revolt”) are often interpreted as similarly unflinching, in-depth examinations of empty sex and drug-fueled anomie. Beyond the lingering full-frontal nudity and simulated oral sex, they are larded with bizarre pornographic images: masturbation with Coke bottles, a sex-obsessed wife tying a ribbon around her vacant husband’s penis, a woman slobbering over a gigolo in the middle of a feminism debate. Morrissey’s key themes usually involve: 1) married, self-loathing bisexuals trying, in vain, to be straight; 2) slutty women or transsexuals trying, in vain, to arouse a zonked-out male sex symbol; 3) older men trying to seduce or exploit said male sex symbol; and 4) characters reacting wanly to something disturbing, such as a graphic rape story. His characters speak monotonously, in either mush-mouthed or stringent cadences, about selfish, empty pursuits, and their calculatingly obscene (if mostly improvised) dialogue never lets us forget that we are meant to find them pathetic.

Yet Morrissey regards these films (and most of the ones in his catalogue) as “comedies.” That he’s not above ridiculing the druggies and sex freaks that he feels sorry for injects his films with an unquestionable tone of superiority. But as much as he may have disapproved of his cast members’ lifestyles, Morrissey adored their enthusiasm for being on-camera, and he was very tolerant of gender-bending, as he employed a slew of transsexual performers. He was able, somehow, to be preachy and admiring at the same time.

His casts were aware of these ironies. In a phone interview with Holly Woodlawn, the transsexual Puerto Rican star of “Trash” and “Women in Revolt,” she confirmed that Morrissey, despite his firm Republican beliefs, never lectured her about her habits. She added that Morrissey had ample reason to make fun of druggies.

“I was one of those pathetic people,” she said. “But to someone that doesn’t know what we went through, we are funny. When I see people in my age group or even a decade younger, doing heavy-duty drugs, it’s wrong, it’s pathetic. But it’s a joke, in a way. I don’t laugh to make fun of them. I laugh, because it’s like, ‘When are you gonna learn? Your teeth are gonna fall out.'”

Joe Dallesandro, the star of several Morrissey films who has also survived years of drug addiction, has similar opinions of Morrissey’s intended vision. “He wanted to show drugs for what they really were,” he told Interview Magazine last year. “I mean, the biggest hope a drug addict could have was to get on welfare, you know? So I think he made his little points in his films.”

But what does a modern-day audience, already well-schooled on the vapidity of 1960s-70s urban hedonism, get out of Morrissey’s films? I watched nearly all of them in a relatively short period of time, and I found the Warhol-produced ones pretty exhausting after awhile. The same static framing persists from film to film, further emphasizing the fruitlessness of the characters’ lives. (Morrissey himself seems to get bored with them at times, interrupting conversations with jerky, fast-forwarding editing tricks). Though there’s more character development and slightly more of a story arc in Morrissey’s collaborations with Warhol than in the latter’s earlier experiments, the films are still rather one-note in their obsession with these performers. The camera loves the libertine characters so much that you feel less like a viewer than an eavesdropper, butting in to a chic, exclusive scene, whose members are far less fabulous or important than they think they are.

Regardless of whether his claims of authorship are entirely legitimate, Morrissey’s imprint on the Warhol Factory’s output should never be overlooked. The films he commandeered are certainly not without wit or insight. They are also nakedly vulgar in impressive ways. Though all of them suffer from at least 20 minutes of dull, meandering material, most contain a few lines or scenarios that can still titillate or shock those with concrete notions of “good taste.” But most of them are soured (and rendered even more dull) by Morrissey’s tiresome disappointment, his snorting disdain, towards his entourage’s tendencies (even if he liked them deep down).

I will not be further analyzing the “Flesh/Trash/Heat” trilogy; “Women in Revolt”; “Flesh for Frankenstein”; “Blood for Dracula”; “Mixed Blood” or “Hound of the Baskervilles” (Morrissey’s lone, futile stab at mainstream comedy, a lame Sherlock Holmes spoof). All of them are available on Netflix and most have been widely written about. Instead, I will discuss Morrissey’s harder-to-find films–which I watched via YouTube, AVI downloads, foreign bootlegs, appointments at the MoMA screening room and trips to the George Eastman House in Rochester and Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh–in approximate chronological order. (Sadly I was not able to find a copy of Morrissey’s latest films, the 2010 release “News from Nowhere,” starring Warhol Factory star Viva and shot in Montauk, and the the 2005 Veruschka von Lehndorff doc “Verushcka–A Life for the Camera”; or most of his silent films shot between 1962 and 1965. Three 1964 shorts, “Like Sleep,” “All Aboard the Dreamland Choo-Choo” and “About Face,” can be viewed as extras on the “Heat” DVD, with Morrissey’s commentary).

For $25, I was able to book an hour’s worth of time in the reel-to-reel viewing room at Rochester’s George Eastman House, where I watched Morrissey’s 1962 silent shorts “Mary Martin Does It” and “Civilization and Its Discontents.” Like his later feature-length Warhol Factory films, they are about urban disarray, but the perspective seems to be coming from a calmer, more level-headed, more compassionate Paul Morrissey than the hectoring grump we are used to. Despite several cartoonish moments, the tone is predominantly sad.

For $25, I was able to book an hour’s worth of time in the reel-to-reel viewing room at Rochester’s George Eastman House, where I watched Morrissey’s 1962 silent shorts “Mary Martin Does It” and “Civilization and Its Discontents.” Like his later feature-length Warhol Factory films, they are about urban disarray, but the perspective seems to be coming from a calmer, more level-headed, more compassionate Paul Morrissey than the hectoring grump we are used to. Despite several cartoonish moments, the tone is predominantly sad.

“Mary Martin Does It” begins with a display of photo advertisements advocating for a cleaner New York. Celebrities (including Mary Martin) pitch in by not littering, the advertisements say, so why don’t you? We then see a woman dutifully picking up trash, a do-gooder, seemingly. But her mission to get “filth” off the streets extends to homeless people, whom she lures into threadbare shelters by giving them jugs of alcohol. (Since these bums never re-appear, the implication is that the booze she’s feeding them is poisoned). The bag lady spying on the woman dismantles her plan by emptying all the garbage cans she has just filled into the street. A Chaplin-esque, sped-up fight ensues and the two women chase each other frantically around the Lower East Side, emptying and refilling trash cans the whole time. The bag lady eventually triumphs when the other woman is swept off by a street cleaner, literally killed by the same system she’s fanatically trying to uphold. Morrissey recognizes that one person’s “filth” is another’s way of life, and that there is a negative, disrupting side to a campaign purporting to “clean up” the city.

“Civilization” runs a little longer–about 40 minutes–and it’s a piece of perplexing, macabre slapstick, in which several cold, cut-off people try and fail to connect with the equally damaged needy. It doesn’t sanctify the unfortunate characters; with one exception, they are shown to be impulsive and insatiable. The film is full of Catholic-like miracles, but the miracles are temporary and ultimately futile. The first exchange, for instance, is between an elderly bag lady in a wheelchair and a musician; moved by her condition, he touches her head kindly. The gesture enables her to suddenly spring out of her chair, pulling off her sad cloaks and rags and shaking off her disability. But instead of thanking her healer, she attacks him, tackling him into the street; then she tauntingly tosses his guitar into the garbage. Unable to mollify her, the man eventually kicks and punches her, and she goes back to her pathetic begging routine.

The sequence starring Morrissey himself (who has a formidable presence on-screen; he should have employed himself more frequently) has a similar structure, only he plays a scowling sadist who torments pigeons in the park. Saddened, a crippled hobo follows Morrissey; wanting to be alone but also feeling sympathy, he blows on the hobo’s head, an act that (as in the earlier scene with the bag lady) “cures” the hobo of his ailment. The hobo won’t stop pestering Morrissey, who finally beats him with a lead pipe.

Perhaps Morrissey’s point is that no one should try to “save” less fortunate people, only connect with them on a human or spiritual level; trying to save them indicates a superiority, which they will only resent. But the movie also seems to be condemning the irrational, violent behavior of the homeless characters, so for all we know (especially given Morrissey’s politics), the message could be “Don’t help anyone,” in true Ayn Rand fashion. The ambiguity makes this the most haunting film in Morrissey’s catalogue, and it should be more widely available.

According to Steven Watson’s 2003 book “Factory Made: Warhol and the Sixties,” “My Hustler,” shot in Fire Island over Labor Day weekend in 1965 and released nearly two years later, was the “brainchild” of Chuck Wein, one of Warhol’s promoters. The film, which can be viewed in its entirety on YouTube, has been verified by several key people as being the first Warhol Factory project to involve Morrissey. Maurice Yacowar’s 1993 biography on Morrissey claims that he was the “presiding force of creative control” on all the feature-length films Warhol was credited as “director” or co-director on from “My Hustler” through “Lonesome Cowboys.” According to “Factory Made,” it was Morrissey that told Warhol, “It’s easy. Just move the camera back and forth,” when Warhol was stumped on how to capture both Ed Hood and Genevieve Charbon’s conversation on a beach house patio and the posing of model Paul America (pictured above, right) some 100 feet away.

It isn’t a particularly memorable film, though it documents Morrissey and Warhol’s appreciation for barbed, salty dialogue between gay men and horny women, as they fight over the same hunk. Here, the homosexual and straight woman in question each want to claim Paul America as a houseguest and sex slave. They call him things like “Sugar Plum Fairy,” and they each use a lot of phallic references as they talk salaciously about him. They’re dismayed when they see him flirting with a bikini-clad younger woman on the beach (though, as with many of the studs in Morrissey’s films, the character is later revealed to be a reticent bisexual). There isn’t much of an outcome to their duel over Paul America; the climax of the film centers on America shaving, with another, less experienced bisexual boy, as he schools him on the art of male hustling.

It is inherently comical that stodgy New York Times critics such as Bosley Crowther reviewed films like “My Hustler” to begin with; only Vincent Canby, who began writing for the paper in the late 1960s, had any appreciation for the Warhol/Morrissey aesthetic, and he eventually tired of it. In his July 11, 1967 review, Crowther calls “My Hustler” a “fetid beach-boy film,” lamenting its “sordid, vicious and contemptuous” dialogue, “careless and amateurish” production values and “freakish but hardly believable” characters. He isn’t entirely wrong, but “My Hustler” established a pattern in the Morrissey/Warhol films to come: a bigger emphasis on dialogue, an end to Warhol’s “film until the stock runs out” mandate, and just a speck of plot structure.

What a poster; if only the movie were that provocative! “The Chelsea Girls,” shot in the summer and fall of 1966 and released at the Film-Makers Cinematheque in September 1966, has been analyzed in countless articles and books, but as it’s not on Netflix I wanted to include it in this post. According to David Bourdon’s 1989 book “Warhol,” it was filmed at the Chelsea Hotel, the Warhol Factory and several apartments, including that of the Velvet Underground.

What a poster; if only the movie were that provocative! “The Chelsea Girls,” shot in the summer and fall of 1966 and released at the Film-Makers Cinematheque in September 1966, has been analyzed in countless articles and books, but as it’s not on Netflix I wanted to include it in this post. According to David Bourdon’s 1989 book “Warhol,” it was filmed at the Chelsea Hotel, the Warhol Factory and several apartments, including that of the Velvet Underground.

The three-and-a-half hour result (which can be viewed here) consisted of twelve scenes (all improvised except for two scripted by Warhol collaborator Ron Tavel), with two at a time unfolding simultaneously on a single screen. There is still debate as to whether Morrissey came up with the double reel idea, as well as how much he participated on the film to begin with. As noted in my earlier post, Mary Woronov (who was the only actress in her scene with Ingrid Superstar, Susan Bottomly, and Angelina “Pepper” Davis to have memorized her lines) didn’t remember Morrissey ever being on set, although she said he may have worked on the scenes with Nico. Regardless of how much creative input he had, Morrissey was surely around for at least one scene, in which the temperamental pseudo-guru known as Ondine explodes (verbally and physically) at Ronna Page, then starts yelling about her to someone named “Paul” off-camera.

The double-screen effect makes the film play out like a particularly tedious acid trip. The pattern is that one scene stays silent while the adjoining one is dialogue-heavy; both depict the expected array of gleeful degenerates and eccentrics. A lonely divorcee spends the entire day reading the telephone book, searching for connection; Ondine, claiming to be an “ex-priest,” meets with several woman and alternately lends them advice and screams at them; drag queens dance for gay men lounging on their bed in a drug-induced stupor. In the most memorable scene, the tall, imposing Woronov, playing Tavel’s interpretation of Vietnam War radio personality Hanoi Hannah, dryly menaces three vulnerable, celebrity-seeking women–she physically prevents one woman from answering a modeling agent’s phone call.

Filled with the droning, abrasive music of the Velvet Underground’s John Cale, “Chelsea Girls” is more interesting as a time capsule than an actual film. Parts are engrossing–Ondine unraveling, a poet stripping in front of fiery images–but it plays out like a soporific orgy we’re not invited to. However, I’m a bit taken aback as to how such a popular, trend-setting piece of art is not on Netflix; surely, this is a more culturally important film than “Hound of the Baskervilles” or even Morrissey’s “Dracula” and “Frankenstein” films. And an audio commentary on the filming process would be most desired by Warhol fanatics.

“Bike Boy” and “I, A Man,” both shot and released in 1967, are virtually indistinguishable from “My Hustler” in storyline and execution. The differences are superficial: there’s no beach scenery, as all the locales are either urban streets or the bedrooms of many loose women; the jabbering dialogue is slightly less constant, pausing now and again for some rather chaste love scenes; and the main character’s bisexuality is a little less certain (though certainly hinted at).

“Bike Boy” and “I, A Man,” both shot and released in 1967, are virtually indistinguishable from “My Hustler” in storyline and execution. The differences are superficial: there’s no beach scenery, as all the locales are either urban streets or the bedrooms of many loose women; the jabbering dialogue is slightly less constant, pausing now and again for some rather chaste love scenes; and the main character’s bisexuality is a little less certain (though certainly hinted at).

“I, A Man,” which was supposed to star Jim Morrison via a request by Nico, instead stars his “drinking buddy,” the late Tom Baker, a very wan, smug performer with none of Morrison’s allure. Despite having a gorgeous French girlfriend (Nico), he cavorts with several less appealing women, whom he isn’t particularly nice to. He forgets most of their names, and after bouts of tongue-kissing that would surely excite most of us, he either exits their bedrooms swiftly or sticks around long enough to insult their breasts. The strongest character, the one woman who gets the upper hand, is played by Valerie Solanas (who later shot Warhol). She is the sole reason to watch the film (which can be viewed in fragmented form here).

Solanas is clearly attracted to Baker–her insistence that she’s a lesbian who just wants to “beat her meat” seems spurious–but she rebuffs him, calling him a “fink with the squishiest male ass.” He takes his shirt off to impress her and she says she doesn’t like his “tits” (a funny if obvious bit of retribution). Asking him if he’s queer, Baker responds: “Not since I was young.” (That self-denying concept is repeated in many Morrissey films). The film ends shortly after that, with zero catharsis.

Like “Bike Boy,” “I, A Man” was originally part of Warhol/Morrissey’s 25-hour film (simply titled “****”) and then, according to the web site WarholStars.org, released separately at the Hudson Theater, whose owner called for a sexually explicit film similar to “Hustler.” It wasn’t provocative enough to sway the critics, though. Said the New York Times’ Howard Thompson in his August 25, 1967 review: “And on and on and on the talk drones — getting nowhere, saying absolutely nothing.” (Six weeks later, when “Bike Boy” was released at the Hudson, Thompson’s review dismissed it as “another of those super-bores” that “belongs in the Hudson River.”)

“Bike Boy,” which can be downloaded in AVI format here, is about as interesting as the reason, according to “Factory Made,” for its existence: Morrissey met lead Joe Spencer in the East Village, found him attractive, and told him to call the Factory to invite himself into the movie.

Like “Hustler” and “I, A Man,” “Bike Boy” is about a beautiful but intellectually stunted male sex symbol, who charms gay men and women alike. In this case, he’s a slightly macho but pretty motorbike dude rather than a male model. He’s also a windbag, prone to pretentiously analyzing the romantic loner appeal of the motorbiker.

The film is marginally less dull than “Hustler” only because of the larger cast and slightly sleazier aesthetics. The seven-minute intro scene in the version I watched (which was actually the final scene when the film was first released) merely shows Spencer taking a shower, staring blankly at the camera. There are many more gratuitous ass shots to come. Characters in clothing stores and flower shops talk about opium, sex hotlines, bestiality, with typical Warholian nonchalance. More than one woman calls Bike Boy a “faggot,” often while flirting with him. The jump cuts, choppy edits and whirring noises could induce migraines. The film is most notable for being slinky, sardonic Warhol superstar Viva’s debut; she has a nice disappointed reaction to Bike Boy after he confesses he’s never had sex “at high speeds” on the back of a motorbike.

I would not call any of these films “good”; they’re experiments, and it isn’t surprising that no one was credited as “director” upon their release (the credits were applied later on sites like imdb.com). But “My Hustler,” “I, A Man” and “Bike Boy” should nonetheless be put out on DVD, perhaps in a single box set because of their thematic similarities.

The two films in Morrissey’s repertoire that I most enjoyed watching were “Imitation of Christ” and “The Loves of Ondine,” for entirely subjective reasons (certainly not because of any stylistic improvements). Yes, in both films the camera is jerky, the editing purposefully amateurish, the dialogue annoyingly self-referential, the acting stiff (the late Andrea Feldman, whose screechy Valley Girl voice in “Heat” and “Trash” gave me heartburn, makes her debut appearance in “Christ.”)

But in both films (which were originally part of Warhol/Morrissey’s 25-hour film), there’s a playfulness to the characters’ interactions, not to mention bursts of random decadence, that enhance the rather thin plot. Though both films condescend to the characters at times, there’s a more palpable sense of Morrissey’s secret delight at, even celebration of, their antics, their inspired buffoonery. He temporarily halts his dismay at the effects of drug use; we sense that he feels left out from the scenes in which Ondine indulges in a naked food fight with several gay lovers (“Ondine”) or where the jolly, red-faced Taylor Mead dances through San Francisco with his crotch exposed (“Christ.”) Just for a fleeting moment, he wishes he could revel along with them.

Both films were shot in 1967 but never released in mainstream theaters, only shown at special events. The original version of “Christ” ran eight hours long and was edited (thank God) into a 105-minute version in 1969. I watched both in MoMA’s theater-sized screening room.

Bob Dylan’s “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” plays in three different speeds at the outset of “Christ.” (Perhaps Morrissey finds Bob Dylan as silly as I do; he’s more tolerable in Chipmunk mode). The lead character, played by Patrick Tilden, is more ungainly and sympathetic than in past Warhol/Morrissey outings. Right off the bat we know he’s unstable, as he tells his girlfriend Nico about his near-rape during a stint in a mental hospital. This couple (gasp!) actually cares about each other!

In the next scene, we see Brigid Berlin and Ondine as lethargic married lovers in bed, shooting up heroin (Berlin requests an injection in her rear). As with many couples in these outings, there is talk of the husband being secretly gay (“You’re the only thing keeping me straight,” he says) and there is less love between them than a mutual reliance on heroin.

Then we discover that Tilden is their son. Though they worry somewhat about his maladjusted tendencies (he talks to himself with others in earshot), they are ultimately more bewildered by his overall clean-cut nature; he’s not an addict like them, despite the fact that, as Ondine points out, “He was born so high!” They tease him for being a “proper,” pretentious son, coyly threaten to send him to an effete “French school,” talk about him in the third person as if he’s not in the same room. It’s a shame that Morrissey eventually resorts to implications of incest; the mother is allegedly having an affair with the kid, an unnecessarily gross subplot (though it’s left undeveloped and, happily, never shown).

But despite the expected moments of monotony, “Christ” is a better-paced, better-written (or better-improvised?) film; there’s even some memorable visual details, such as Andrea Feldman’s filthy feet during a bedroom quarrel. Most importantly, when Tilden talks about his tortured past, we care about him; when he tells Nico about his shock treatment, his pain is palpable.

As for “Ondine,” it’s mostly known for being Joe Dallesandro’s debut; he stuck his head in during the shoot and was invited personally by a very smitten Morrissey to join in. But it’s more than that; it’s Morrissey’s funniest, sharpest film. It’s a Warhol Factory film through and through, arbitrary and sloppy, but this one is jazzy and surprisingly fast-paced, an out-and-out comedy. While heavily improvised, the scenes are timed to the rhythms of Ondine’s tart-tongued patter with a coterie of women who dissatisfy him, and (at least for the first hour) never seem to drag on too long. Watching it, you regret that Morrissey did not make Ondine the central figure in more of his films.

As for “Ondine,” it’s mostly known for being Joe Dallesandro’s debut; he stuck his head in during the shoot and was invited personally by a very smitten Morrissey to join in. But it’s more than that; it’s Morrissey’s funniest, sharpest film. It’s a Warhol Factory film through and through, arbitrary and sloppy, but this one is jazzy and surprisingly fast-paced, an out-and-out comedy. While heavily improvised, the scenes are timed to the rhythms of Ondine’s tart-tongued patter with a coterie of women who dissatisfy him, and (at least for the first hour) never seem to drag on too long. Watching it, you regret that Morrissey did not make Ondine the central figure in more of his films.

In the first scene, Ondine tells a female conquest that he doesn’t like “homosexual society” and views her as his “knob to tune into heterosexuality.” He chews her hair, insults her breasts (what is with that recurring theme??) and calls her a “bloody dumb bloody bore–that makes four of you.” As in “Chelsea Girls,” it is very hard to discern whether Ondine is play-acting or is genuinely furious and/or bored with these ingenues.

In a hysterical sequence with Ondine and Viva (pictured above), there is much arguing over how much he should pay her, a call girl, to remove the tape from her breasts. After paying a handsome sum for her to uncover one breast, she charges $400 for the other; his response: “Why should I pay for something I’ve just seen?”; hers: “What if it’s a different color?” (The women generally give as good as they get in this film). The effete, nagging priss Ondine calls Viva “underdeveloped,” then “too far developed,” and finally “overunderdeveloped.” He doesn’t like her smart, he doesn’t like her stupid; he’s appalled when she’s sultry and bored to tears when she’s chaste. He’s a man of his time.

Ondine then has a slightly less angry encounter with a third girl. After telling her, “I like to torture women, including my mother,” the film abruptly cuts to the aforementioned food fight orgy. Words do not do it justice, but I’ll try: several naked and half-naked men hurl milk and flour and pizza at each other and then gyrate around in the sludge, with The Beatles’ “A Day in the Life” and “When I’m 64” humming in the background. It is certainly the film’s high point.

The rest is, disappointingly, like a lot of weaker entries in Morrissey’s portfolio. There are pseudo-provocative rape stories, endless shots of Ondine fondling younger men, a homoerotic flaunting of Dallesandro’s prowess as he and Ondine wrestle. The film kicks up a notch when Brigid Berlin barges in, revealing herself to be Ondine’s wife (they are evidently the same characters from “Christ.”) She’s furious that her husband gets to romp around with pretty boys while she’s stayed faithful, but her resentment doesn’t last long; soon she’s wrestling with Dallesandro too! There are motifs about this couple’s arrested development (they play with their son’s talking toy parrot, and their blankets display Disney characters). There’s even a flubbed line left in, when Berlin says “This is where our only son was consumed” instead of “conceived.” Then the film just ends. It’s a mess, but a very enjoyable one, and it should, along with any other films culled from “****,” be placed on a retrospective DVD.

I ordered a Region 2 Italian import of “Lonesome Cowboys” off Amazon.com, and I’d have to say I agree with Vincent Canby’s May 6, 1969 New York Times review that it is the “least interesting, most banal” of the Warhol/Morrissey films. Shot on a ranch near Tucson (the same area where several John Wayne flicks were filmed) in early 1968, it is supposed to be a homoerotic Western version of “Romeo and Juliet.”

Though the central couple is still straight (played by Viva and Tom Hompertz), this “Romeo and Juliet” are upstaged by the more colorful subsidiary characters, a pack of predatory gay cowboys who want to take over Viva’s ranch and boy-toy. There’s one nice twist: when the couple plans to commit suicide, they buy a sleeping pill from a gay apothecary clad only in a spangled Speedo. But generally, “Cowboys” flaunts the same tired theme of forthright females versus forthright gays, with some chaste sex and cavorting to rock music (in this case, The Beatles’ “Magical Mystery Tour”) thrown in. Even for a Warhol/Morrissey film, the camerawork and sound is horribly amateurish, with gusts of wind often drowning out the dialogue. And occasionally the film is downright cruel, as when the cowboys tackle and disrobe Viva, laughing at her screams.

The movie is even worse than Alex Cox’s 1987 comic western “Straight to Hell,” a similarly self-indulgent film in which hip non-actors gathered in a dusty town and made merry, to the delight of no one but the director. The behind-the-scenes stories about it are far more interesting. Viva refers to Andy Warhol by name during the simulated rape scene, begging him to stop the shoot; she was reportedly injured, though some cast members, like Taylor Mead, have avowed she was being overly dramatic. The film was later seized by authorities before being screened in several cities, as they had heard of the infamous rape scene and believed it to be real. Brigid Berlin and Ondine were invited to join the cast but reportedly refused because they worried about the paltry supply of amphetamines in the Southwest (if only they’d been around for the crystal meth craze). Legend has it that Warhol edited the film while recovering from his gunshot wounds, which could account for the anemic pacing.

Far more enjoyable is “San Diego Surf,” which featured many of the same cast members from “Lonesome Cowboys.” Filmed in May 1968 in La Jolla, California, shortly before Warhol was shot, it was shelved for decades before Morrissey finalized the editing, in 1996. I was fortunate enough to catch MoMA’s NYC premiere of the film in October, where Taylor Mead gave a rambling if funny introduction.

Far more enjoyable is “San Diego Surf,” which featured many of the same cast members from “Lonesome Cowboys.” Filmed in May 1968 in La Jolla, California, shortly before Warhol was shot, it was shelved for decades before Morrissey finalized the editing, in 1996. I was fortunate enough to catch MoMA’s NYC premiere of the film in October, where Taylor Mead gave a rambling if funny introduction.

In December 2011, Morrissey told Interview Magazine that Warhol had “nothing to do with [the film], except his terrible camera work, which I even had to take over most of the time.” As mentioned in my earlier post, the short behind-the-scenes documentary of the “San Diego Surf” shoot, called “Andy Makes a Movie,” clearly shows both Morrissey and Warhol operating cameras. When Warhol is asked by an interviewer which one of them does most of the technical work, he skirts the question to answer the doorbell. But there’s a lot of Morrissey-esque wit in “Surf,” so it’s pretty definite that he oversaw the actors’ improvisations.

Morrissey noted in the same Interview piece that the film “didn’t work,” as “there just wasn’t enough there to edit. You can’t edit something that’s not good to begin with.” To lend the film a tinge of shock appeal, he tacked on an ending, shot in New York, in which Taylor Mead begs a laconic surfer to urinate on him, as a sort of “initiation” into the surfing lifestyle (what golden showers have to do with the sport of surfing, I’ll never know). After 20 minutes of Mead’s wheedling (which is upstaged by the camera’s fascination with his exposed, flaccid penis), the surfer complies, and we get a delicious close-up of the (simulated) act just before fade-out. (Viva has said she hated the ending).

Perhaps the empty hedonism on display here feels more at home in the relaxed beach-house setting. Viva and Mead are a bored couple who (surprise, surprise) both lust after surfers. They have a 20-something daughter (Ingrid Superstar) and a baby daughter (whom Viva, in real life, almost drops at one point; Dallesandro saves the day!) Viva tries to convince Superstar to have an abortion; she also wants to set her up with a surfer husband. Sensing his wife’s unhappiness, Mead suggests an open relationship so she can sleep with surfers and he with both the surfers and an exotic black woman (an exploitative, racist addition to an otherwise innocuous film). The surfers are for the most part appropriately dim, but one of them–I think the one with the moustache–occasionally waxes intellectual about the advantages of polyamory: “Why not have one guy for a minute or an hour or whatever? He’s yours for the present.”

“San Diego Surf” would probably have bored me more if I hadn’t watched it with a live audience. To my delight, some people stormed out angrily while others gasped in amused horror at stunts like the piss scene. I’m thankful that Morrissey committed to finishing the movie, and he should negotiate with the Warhol Foundation for it to be released on DVD.

In 1971, Morrissey took part in an improvisatory film project assigned at the Belgrade Film Festival. He and fellow directors Karpo Acimovic-Godina, Tinto Brass, Mladomir Djordjevic, Milos Forman, Buck Henry, Dusan Makavejev and Frederick Wiseman each shot three minutes worth of material dedicated to Sonja Henie, the Norwegian figure skater and movie star, who died in 1969. The 15 minute final film, which can be watched on YouTube, was called “I Miss Sonia Henie.”

The production is certainly slipshod. False starts and bad takes are left intact. Scenes shot by different directors yet containing the same cast members and locations are randomly thrown together, making it hard to know what’s going on or who should be credited for what (though Morrissey’s scene is easy to detect because of the nonstop mock fellatio). Certain Morrissey themes prevail, such as empty sex and cuckolding. The only “story” that seems to be followed through from beginning to end involves a constipated man and a lustful woman with a (literal and figurative) itch. “I Miss Sonia Henie” is a rather dull affair whether you’re familiar with Henie or not.

Shot in Paris a little while after completing his “Flesh/Trash/Heat” trilogy, Morrissey’s “L’Amour” is frivolous, slaphappy fun–if you can get around star Michael Sklar’s squawking, horse-laugh delivery. (“L’Amour” is the only Warhol Factory film I watched that features a total nerd–albeit one that swings both ways–as the central figure).

I traveled all the way to Pittsburgh’s Warhol Museum to watch a VHS copy of “L’Amour,” possibly the sole remaining copy (the film is extremely difficult to find). It is certainly not great art, but I see no reason why this film can’t be released on DVD. If nothing else, it is an interesting anomaly in the Warhol/Morrissey catalogue in that other figures in the Warhol Factory were as responsible for the film as either man. According to Bob Colacello’s 1990 book “Holy Terror: Andy Warhol Close Up,” it was Warhol’s manager Fred Hughes that financed the film, and investors insisted on an official script. Though credited to Warhol and Morrissey, Hughes reportedly interfered with a lot of creative decisions during the shoot, demanding certain locales. Furthermore, Warhol’s then-boyfriend Jed Johnson handled much of the camerawork.

Generally, “L’Amour” has more mainstream elements than in other Morrissey/Warhol films, such as a legitimate opening credits sequence and a theme song (by Cass Elliot). While the familiar theme of gay men and straight women lusting after the same playboy continues, the women in this picture are more innocent, less lascivious; they talk more about missing American hamburgers and soap operas than their past trysts. Still, “L’Amour” retains the loose, meandering feel of past Warhol/Morrissey outings.

Two vapid, hippie models (Jane Forth and Donna Jordan) visit their friend (Patti D’Arbanville) in Paris. She’s married a rich man and wants them to do the same. An extended make-over scene follows, in which we get many glimpses of the stunning D’Arbanville naked in the tub, her face dripping mascara. Before getting dressed, the girls engage in much topless horsing around: belly rolls, ass-slapping, giggly leg-waxing. Pretty soon D’Arbanville drops out of the film. (As she told Interview Magazine in 1973, “when I’m in improvised films I just tend to overact because there’s no real direction. There’s such freedom in something like ‘L’Amour’ that I just run wild. I mean, at times I was just foaming at the mouth.”

The main plot involves a handsome French gigolo named Max (Max Delys); his sugar daddy Michael (Sklar), a whistling, crocheting, klutzy buffoon who’s taken over his father’s deodorant company; and their plan for Michael to marry one of the visiting women so they can legally “adopt” Max as a son (a ridiculous subplot, as Max is clearly not a minor). Michael is smitten with Max and has somehow tuned out his promiscuous ways; he wails like a bleeding banshee when he discovers Max’s infidelity, but Max insists that he never loved Michael. Instead, Max pines ineptly for Jane; his idea of sweet-talking is “I would like to sleep with you, not do anything, just sleep. Just to smell you beside me, to feel you.” Max is so pretty that Jane does eventually join him in bed, but the sex is pathetic, ruined by her demands to keep her shoes on and her whining about missing American culture.

Meanwhile, Michael behaves like a total jackass with Donna, who is oblivious to his gay tendencies even after he loudly proclaims them. After writing up an inane high school musical and casting the ladies in it, he chuckles, “I didn’t know girls were so much fun. I guess I’m missing out!” Later, when he’s in bed with Donna, he says, “I got a surprise for you…it’s long and hard and big,” and then pulls out a giant baguette. Grapes, fruit, cheese and Max are all Michael desires, but Donna marries him anyway (presumably for his money). Jane ultimately rejects Max, returning to the US to get her high school diploma and watch her talk shows. The ending is wistful and surprisingly poignant, as the miserably married Michael watches his unrequited love skip away with a younger man.

Vincent Canby’s 1973 New York Times review of “L’Amour” indicates that he had long run out of patience for Warhol/Morrissey experiments. “These things simply are not funny or important enough to compete with late-night talk shows, a new album by the Carpenters, the Watergate scandal, kung-fu movies, dining at Blimpie’s, and a number-one best seller by Jacqueline Susann,” he wrote. Inconsequential as it is, I find “L’Amour” to be more important as a cultural touchstone than any of those things (except Watergate, of course).

Disregard Warhol’s name at the top of this poster. After shooting “Flesh for Frankenstein” and “Blood for Dracula” (which bore Warhol’s name as producer/distributor), Morrissey permanently parted ways with Warhol, sometime during the late 1970s. By the 1980s, he was financing his own films, the first of which was the 1981 comedy “Madame Wang’s.”

Disregard Warhol’s name at the top of this poster. After shooting “Flesh for Frankenstein” and “Blood for Dracula” (which bore Warhol’s name as producer/distributor), Morrissey permanently parted ways with Warhol, sometime during the late 1970s. By the 1980s, he was financing his own films, the first of which was the 1981 comedy “Madame Wang’s.”

I ordered a bootleg of the film off the auction site iOffer.com. It was probably taped off of European television; as Morrissey told the Los Angeles Times in 1986, the film was never distributed in the US, “just in places like Belgium and Holland and Australia. You don’t get rich from that.”

The star of “Madame Wang’s” was a real-life German medical student (now, to the best of my knowledge, an orthopedist and trauma specialist in Berlin) named Patrick Schoene. With his unkempt hair, sternly handsome face and habitual scowl, Schoene is a shoo-in for the young Morrissey. Fresh off the boat from Germany, he ends up in Redondo Beach, California, and his first order of business is to slash his legs with a pocket knife (what led to this masochism is never explained).

Then he meets a prostitute who invites him to crash at an abandoned Masonic temple, filled with the expected cornucopia of Morrissey-approved outcasts. There are bums peddling ridiculous objects such as doorknobs and jars of mustard; a fat, Shelley Winters-esque pimpette (played by a transsexual), who put her own daughter on the street to “meet a higher class of people”; and an assortment of gay and straight punk rockers who are slavishly devoted to Madame Wang’s, a punk rock club/Chinese restaurant owned by another fat woman (and obviously a parody of the 1970s Chinese restaurant/showroom Madame Wong’s).

The greatest joys of “Madame Wang’s” come from the performances at the title punk venue. Morrissey is clearly no fan of punk, and if he admired these performers the same way he admired the transsexual casts of his Warhol years–or bothered to learn about the actual punk genre–the film would pale in comparison with, say, the true-blue punk documentary “The Decline of Western Civilization.” But his disgust gives these sequences a certain berserk energy, as if the film was a documentary on gangsta rap made by Bill O’Reilly. Naivete and disdain can breed wonderful results; Morrissey’s skewed version of punk is hilariously bad and easy to hate. Most of the bands, for instance, lack a drummer. A lesbian poet named Frank plays folky, arrhythmic love songs (sample: “People call her ‘junkie,’ but she was in a methadone clinic and I respect that.”) One band has a singer dressed in a giant bumblebee outfit.

The only notable (and decent) band on display here is the Mentors, whose members played in executioner’s masks and sang deliberately misogynistic lyrics such as “Good lady on the street/your ass looks so sweet/you don’t have to sleep outside anymore!” (In one of my favorite on-screen interviews of all time, in “Kurt and Courtney,” Mentors’ frontman El Duce tries to disprove Kurt Cobain’s suicide, claiming he knows who Courtney Love paid to “whack” Cobain; at one point he seems to out his own friend as the murderer, which may or may not have led to Duce’s sudden death weeks later; the dubious explanation is that he was run over by a train). I wrote to Mentors bassist/founding member Steve Broy (whom I’d written to in 2005 with a question about the band) and sent him my copy of “Wang’s,” which he enjoyed, but he had no recollection of being in the movie.

The rest of “Madame Wang’s” is low-wattage camp. The sound is horrible, with much echo-chamber shrieking. The acting is uniformly wooden, especially from the man playing a yuppie husband, whom his slutty housewife hires the German to kill. The German is surly to everyone, not just the whores trying to sleep with him and the weirdos trying to bring him in on illicit business, but people housing and feeding him, too. Every liberal he meets, regardless of temperament, is seen as part of the overall hedonistic disease that’s eating away at America.

The character is supposed to embody Morrissey’s personal respect for the so-called tidy, civil ways of East Germany and Russia at the time (a confusing viewpoint given his public outcries against Commies). When the character is revealed to be a spy working for Russia, to school the Russians on America’s ways so they are better prepared to infiltrate and “take over” the country, that clearly represents Morrissey’s secret wish that someone (if not Russian officials) would barge in and sanitize America. (It’s a sort-of backwards “Red Dawn.” Paul Morrissey hates our freedom).

When the German’s masochism is discovered, of course the punks consider him a natural and invite him to perform in their club. But he’s too pristine and solemn to make a career out of it, so he heads back to his homeland, with Roaring Twenties jazz in the background. “Madame Wang’s” is sour and stupid, but it’s funnier than a lot of the Warhol-era films and should certainly be on Netflix.

Shot in the early 1980s but not theatrically released until a 1996 Morrissey Retrospective program in New York City, “Forty Deuce” is an insanely over-the-top portrait of Mayor Koch-era Times Square gigolos and drug pushers. Featuring Kevin Bacon (who also appeared in Alan Bowne’s play of the same name), Esai Morales and Orson Bean (who played the kindly, eccentric old employer in “Being John Malkovich), it is notable mainly for its homemade brand of what Tom Wolfe would call “fuck patois.” Nowhere else will you hear the words “shit” and “fuck” used in such ways as “What you shit what I do?” or “Shut your fuck!”

There’s also an ample barrage of racist and homophobic put-downs, some of them quite clever. “All those greasy wops in Brooklyn, how come it don’t slide into the ocean?” inquires one pusher. When Bacon and Keyloun meet with some black dealers, negotiating who gets reign over which stretch of the city, Bacon gives the following sales pitch: “You want a piece of the fags, you can’t find a better outlet.” The obligatory pimp character calls his boys “testicles.”

Steven Puchalski of Shock Cinema Magazine kindly sent me a French import copy of “Forty Deuce,” and I got a perverse kick out of the English-to-French translators’ grappling with all the slang. Example: the various terms for homosexuals are sometimes translated as “pédé” (short for “pédéraste”) and sometimes simply as “gay”; the term “horse,” slang for heroin, is translated as “cheval,” as in the actual animal.

The plot is minimal and stagy. In the gruesome opening scene, a 12 year-old “customer” is found dead from OD’ing in the pimp’s hotel room. The first half of the film shows the gigolos hustling, pushing, swearing and panicking as they figure out how to cover up the crime. They decide to pin it on their middle-aged, perverted rival (Bean) by getting him knocked out on junk, moving the little boy’s corpse to his bedroom, and making him believe that he is responsible for the kid’s death. That plan is orchestrated in the needlessly lengthy second half, with Morrissey reusing his showy dual-screen device from “Chelsea Girls.”

Stephen Holden panned the film in his New York Times review, saying it “aspires to be a hard-boiled David Mamet-like fusillade and misses by a mile.” Morrissey himself called it “the most horrific thing I’ve ever done” in a 1988 Globe and Mail profile. When I interviewed him, he denied having said this, calling the film and his cast “wonderful.” I believe he meant that it was the closest visual approximation he could muster of New York City as a “toilet world,” one of his favorite descriptions. “Forty Deuce” is a dreary outing, but there’s likely a few sordid Netflix subscribers that want to watch Kevin Bacon turn tricks in the Port Authority Bus Terminal men’s room.

Pretty part of content. I just stumbled upon your weblog and in accession capital to say

that I acquire actually enjoyed account your

weblog posts. Anyway I will be subscribing to your augment and even I

achievement you get admission to constantly fast.