King’s origins as a filmmaker are as far removed from the Hollywood action genre as you can imagine. A history major at Stanford who later studied film at MIT with Richard Leacock (the cinéma vérité director most notable for his work on “Monterey Pop”), he spent a chunk of the early 1970s shooting scores of documentary shorts, about drifters, about Chinese poetry, about his friends. Now in his early 60s, King has come full circle, again devoting most of his career to non-fiction works, albeit slicker, higher-budget ones such as “Shark Week” specials for Discovery Channel and biographical films for The History Channel.

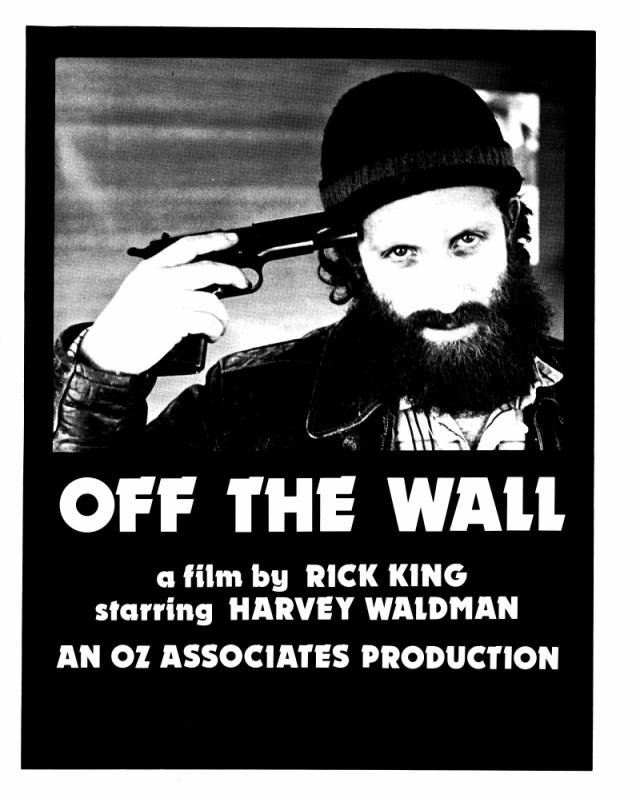

But in between 1975 and 1997, King directed 12 feature films (three of which he co-wrote), whose subject matters are all over the map. Since his 1977 debut, the now impossibly hard-to-find pseudo-documentary “Off the Wall,” his movies have ranged from earnest dramas about juvenile delinquents (“Hard Choices”) to deliberately junky teen exploitation outings (“Prayer of the Rollerboys,” starring the late Corey Haim as a heroic pizza boy who saves post-apocalyptic Los Angeles from droves of Neo-Nazi rollerbladers). He lends the same steady hand to fast-paced erotic thrillers (“A Passion to Kill,” “Quick”) as he does to more thoughtful, ambitious works like “Forced March,” in which a B-movie actor tackles his first serious role as a real-life Hungarian Jewish poet and Holocaust victim.

King cites Akira Kurosawa, Frederick Wiseman, François Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard as chief influences, but none of his films could be called homages to these artists. What one can certainly detect is an impressive straightforwardness, a knack for telling a story cleanly, a calmness that projects his confidence in the audience to interpret his films in their own way.

King always had a fondness for documentaries, and of his fiction films, he still favors the ones that hew most closely to reality. The main inspiration for “Hard Choices,” for instance, was photojournalist Stephen Shames’ account of minors jailed in an adult Tennessee prison. “Off the Wall’s” comic high points are derived from its star Harvey Waldman’s juicy real-life anecdotes.

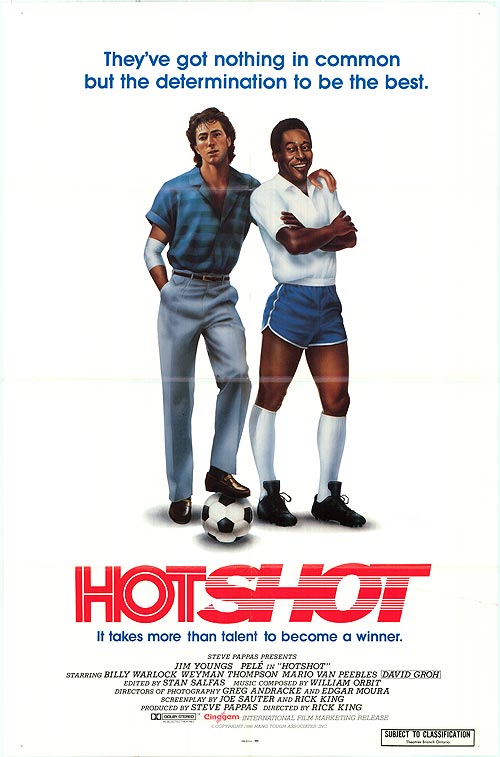

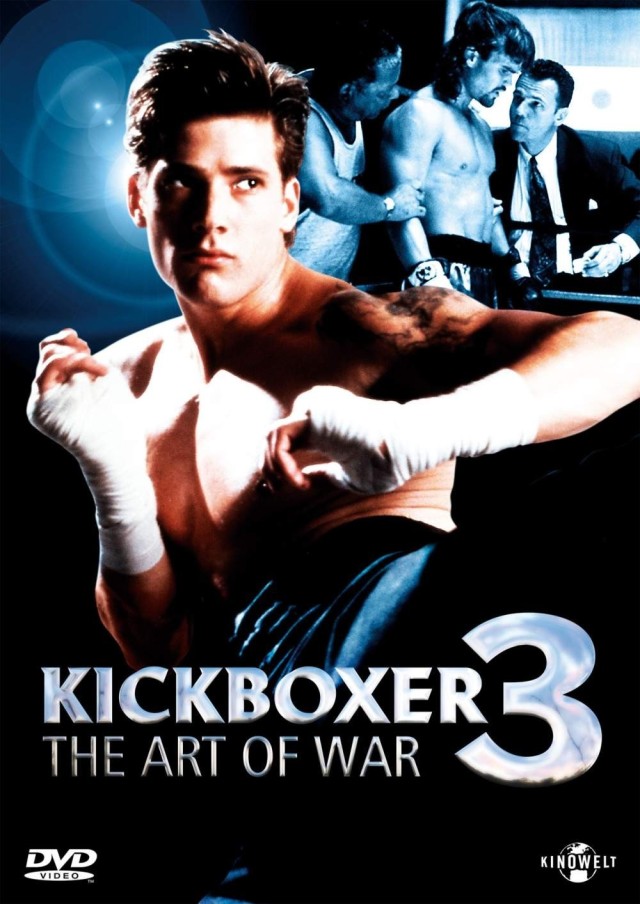

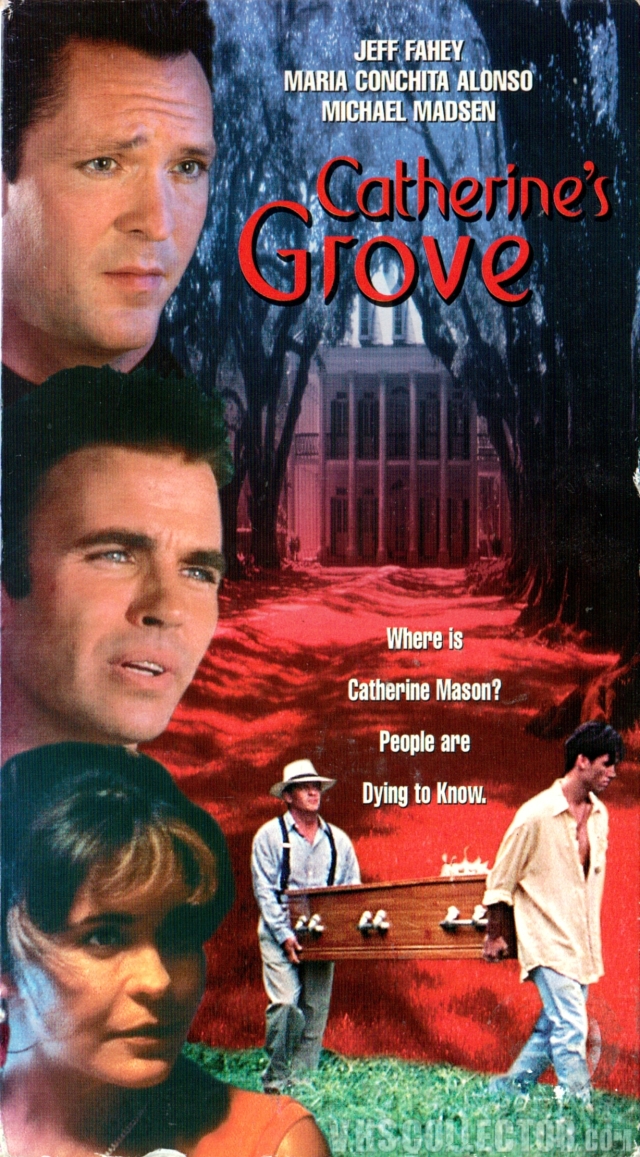

But he’s also been a devoted, practical family man, and he was never too proud to take a job solely to put food on the table (the forgettable 1987 Pelé vehicle “Hotshot,” the second “Kickboxer” sequel starring the irascible Sasha Mitchell). While some of his films have been less well-received than others, none have marred King’s diligent reputation. His last few feature films in the late 1990s (“Catherine’s Grove,” “Road Ends”) went virtually straight-to-cable, but their shoestring budgets allowed King creative control. As a result, they are commendably above-average B-pictures; the latter film is notable for a rare kindhearted role from Dennis Hopper.

King misses feature films sometimes–and still has a few left in him, though little time to develop them. But as a filmmaker who gets flown to New Zealand (for scuba diving shoots) and other exotic stretches of the world (Egypt, The Arctic), he has few complaints.

When I spoke to King over the phone, from his home in Santa Monica, we discussed (among other things) why he decided to make his debut film about–in his words–“the last hippie”; his tumultuous experiences working with Corey Haim, Sasha Mitchell and Bill Paxton; and how, had he served as director, he would have improved the final cut of “Point Break.” (NOTE: Given the nature of this web site, I chose to focus less on King’s films that are available on Netflix, namely “The Killing Time,” “Terminal Justice,” “Road Ends,” “Kickboxer 3” and the documentary on war-related poetry, “Voices in Wartime.” “Voices” and “Road Ends” are the best of this lot.)

Finding a print of “Off the Wall” was the most challenging, fun experience I’ve had so far for Hidden Films. It is King’s only film that can’t be found anywhere on-line or even at cult video stores. Shot sporadically between the summer of 1975 and early 1977, it was shown at Cannes and other European festivals and given brief theatrical runs in San Francisco, Cambridge and New York City’s Whitney Museum and Bleecker Street Cinema. But though it received some stellar reviews (aside from the New York Times’ chief critic Vincent Canby, who panned it), it disappeared after its quick release, never to be distributed on video.

When I first wrote to Rick King several months ago, he said that he only had a 16mm print of the film but was planning to make a digital copy. Months after, I tracked down Marly Swick, credited as “Off the Wall’s” co-screenwriter (she’s now a published novelist and creative writing professor at University of Missouri). She told me that, sadly, she only had an “Off the Wall” t-shirt, that despite her writing credit she did not contribute much to the screenplay, and that if anyone would have a copy, it’d be Rick or lead actor Harvey Waldman. Twenty minutes later, I found an imdb.com user review of the film, with the heading “A time capsule of mid ’70’s California alienation.” The user’s name was hw3074. HW. As in (I guessed correctly) Harvey Waldman!

I wrote to Harvey and a few days later he replied that he did, in fact, have a VHS print of “Off the Wall,” perhaps the only one in existence. In another stroke of luck, it turned out that Waldman works, as a line producer, just down the block from my day job! He said that he would loan me the tape if I agreed to make a DVD copy for him. Scared to break the video in my unreliable VCR, I made a copy for myself as well, and watched the film.

“Off the Wall” profiles John Little (Waldman), a bearded, bisexual, down-on-his-luck California hippie, whose shambling lifestyle and unpredictable temperament endear him to an amateur documentary film crew. Being put under the spotlight only heightens his self-loathing, however, and after a few failed job interviews and struggles with his friends (including a junkie, played by King himself), he begins to snap. One day, the crew follows him to a bank, which he holds up; he also steals the crew’s equipment so he can take over directing duties, as he is resentful at how he was depicted.

The rest of the film tracks John’s aimless wandering around the country, having fleeting, shallow flings–off-camera–with male hitchhikers and poly-amorous women. Mostly, he just grows more and more disenchanted, with America, with his realization that the hippie movement didn’t really change America for the better, with his own alienation. “Off the Wall” ends with John hiding the video camera in a Greyhound station locker. “So long,” he says to the camera, before heading off to God knows where.

As seen today, “Off the Wall” is a indeed a fascinating time capsule. The film was ahead of its time in that it was one of the first to apply the documentary format to fiction. The only obvious predecessor is Jim McBride’s 1967 film “David Holzman’s Diary,” in which a similarly disillusioned, New York City loser struggles to make an involving film out of his dull life. But I found “Off the Wall” more entertaining, maybe because the characters are a loopier brand of distinctly Californian kook. For this reason, it absolutely deserves to be released on DVD, and should be shown to aspiring documentarians.

King’s fly-on-the-wall approach to the material results in some staggeringly powerful scenes, mostly when the camera just watches random disarray happen. Because of its shoestring budget (Waldman estimated that the film cost around $30,000), the film’s visuals are as no-frills as you can imagine (the getaway scene following the robbery is eerily blasted out with actual sunlight). There are tracking shots of dead cows, ugly industrial lots replacing mom and pop stores, and long unemployment lines, often accompanied by radio broadcasts of screaming union organizers and news reports about snipers. (King filmed all this on two separate road trips, one through the Southwest and the other from Virginia to San Francisco, and the movie could use more snippets from these journeys).

Though “Off the Wall” would benefit from a tighter structure, its ambling pace is often what makes it so charming. If John was just a bitter mope, the film would be tiresome, but he has a tendency to shift into playful sprite mode, parading around nude, stealing cheese from a grocery store with a puckish smile on his face. We’re on his side, and it’s sad when it becomes clear that he isn’t going to achieve much.

The bare-bones, meandering story could be meatier. While the first half presents John as an intense, prankish eccentric, his character becomes more muted and dull following the robbery. Because he is off on his own, his mischievous rapport with the film crew and his housemates comes to an end, and so we’re left with his voice-overs, which are rather tongue-tied (“I’m staying at this house. It’s mellow”; “She left me. What can I say? I asked her not to.”)

King and Waldman wanted “Off the Wall” to be a commentary on the sudden lack of a counterculture movement in California following the Vietnam War. “There was no opposition against the system, and [we showed] an archetypical person who was lost as a result of that,” Waldman said when I spoke to him at his office. King added, “It’s like everything had passed him by and he was still there with long hair, and everyone else had sort of moved on.”

But to evoke that mood of terminal confusion and disassociation, “Off the Wall” needed more scabrous dialogue, more interactions with random stragglers, rather than its recurring scenes of John brooding silently. Or at least more of a sense that John is in danger after his robbery. The film is perhaps a bit too freewheeling to work as commentary on such a heady subject.

Still, “Off the Wall” deserved its plaudits and deserves a revival. In Canby’s lazily dismissive review (which “broke my heart a little,” Waldman admits), he critiqued Waldman for behaving like “a bearded actor improvising aimlessness on film.” But that very aimlessness is fun and infectious. The film seems like a gentler precursor to one of my favorite shows, the Canadian series “Trailer Park Boys,” which also tracks a documentary crew filming small-time, lovable low-lives that resort to petty crime.

After the short US theatrical run, King said, “I was just restless. Universal Studios was gonna look at the prints. We only had two or three, but we needed them for Europe, so I just pulled them. I was very impetuous, and a bit precious, to be honest.” He settled in Paris for awhile, taking odd jobs cutting news reels, and then worked as an editor back in the US for various news and television shows. His next feature film was “Hard Choices,” shot in 1984 and released two years later.

Waldman worked with King around a decade later, as first assistant director and close collaborator on “Forced March,” and they are still great friends to this day. He more or less resigned from acting, except for bit parts in films such as “The Stuff” and “Bleeding Hearts.” He assisted Wim Wenders on “The American Friend” and Allan Moyle on “Times Square,” and later served as assistant director on “Pee-Wee’s Big Adventure,” “The Hard Way,” “Buffy the Vampire Slayer” and many other films. Since the late 1990s he has mostly worked as a line producer and unit production manager, including for the recent “Mildred Pierce” six-hour mini series directed by Todd Haynes. He is now working on “Broadway 4D,” a 3-D film musical of actors performing Broadway numbers, which will be shown at a soon-to-be-renovated movie palace on 42nd Street. He is also developing “The Berkeley Connection,” a nostalgic film in the vein of “The Big Chill,” with screenwriter/director Marshall Brickman.

Looking back, Waldman’s chief complaint about “Off the Wall” is its lack of music. “There’s a moment where John Little is sitting on the couch and there’s a speaker above his head. There should be music there!” he said. “But I’m very proud of the film. It’s a fantastic document of that period.”

I want to meet (and hug and kiss) whoever came up with the second “Hard Choices” poster above, which makes the quiet, sincere drama look like a straight-to-Cinemax shoot-’em-up action thriller (perhaps starring Michael Paré or some other ’80s beefcake). Neither King nor producer/co-writer Robert Mickelson mentioned this astonishingly egregious marketing ploy to me during interviews. But whether they approved the poster or not, it did little to hinder (or perhaps helped) the highly successful theatrical run of “Hard Choices,” the happy result of an exciting (but grueling) two-year effort. Though it has some flaws, “Hard Choices” is easily King’s finest film (though maybe not his most slickly entertaining–that award goes to “Quick”).

Mickelson and King first collaborated on a PBS film about Philadelphia. Throughout the early 1980s, they edited trailers and promotional films for Time Life Films. When renowned photojournalist Stephen Shames invited Mickelson down to Tennessee, to watch him interview teenagers jailed at an adult prison, Mickelson brought King along. The interviews wound up forming part of the plot for “Hard Choices.” The other part was based on the true-life story of Mary Evans, a 27 year-old lawyer who, in 1984, busted her 36 year-old client/lover out of prison and escaped authorities for five months. For the film, King and Mickelson changed the female lawyer to the character of social worker Laura (played by Margaret Klenck), and turned the prisoner/love interest into a 15 year-old boy named Bobby (Gary McCleery), accused of aiding and abetting his older brothers in a drug store robbery-turned-murder.

King and Mickelson brought “Hard Choices” to Sundance in January 1985. Though the Coen Brothers’ “Blood Simple” won first prize at the festival, Mickelson recalled, many judges hailed “Hard Choices” as the more deserving film. The movie then entered Los Angeles’ Filmex festival, and after the LA Times’ critic Sheila Benson wrote a flattering profile, 800 people showed up to the initial screening. That led to a flurry of calls from studios, and Mickelson and King ultimately chose Lorimar.

The resulting experience was far from smooth. “Lorimar had no idea what to do with it,” said King. “People had seen it around Hollywood, but nothing was happening. Robert, to his eternal credit, dug up some clause in the Screen Actors Guild contract, that if the film was released theatrically, the residuals from the video sales would be reduced. So it was in Lorimar’s interest to release the film theatrically. They said that would cost money and we said we would put up the money.”

As with “Off the Wall,” the release of “Hard Choices” was largely financed through private fundraising, though it cost a sizable amount more, around $500,000.

“Robert raised money, and I think my father put in three or four grand,” King remembered. (One of the key financiers Mickelson found was also responsible for “Liquid Sky,” the cult 1983 film about chic, miserable aliens taking drugs and having sex in New York’s then-debaucherous East Village.) With pre-paid ticket machines yet to be invented, block-long theater lines were still a common sight, and Mickelson and King seized every opportunity, upon their film’s New York City release in the spring of 1986, to promote “Hard Choices” face-to-face.

“We went to the independent films that had the biggest lines, like ‘My Beautiful Laundrette,'” said Mickelson. “We’d hand out flyers, shaking hands with everyone, telling them about our film. Once the film got great reviews, we’d go to the lines with our reviews. By the fifth or sixth week, we [grossed] about $16,000 per screen. Then we started getting calls from all over the country.”

Reviews for “Hard Choices” were overwhelmingly positive, particularly from the late Roger Ebert, who placed it on his year-end Top Ten list. Even the less enthused reviews–from Canby as well as The Washington Post’s Paul Attanasio–had plenty of laudatory remarks on the production values and acting. Canby, who was infatuated with both Klenck’s performance and her character, was decidedly less taken with the central teenage boy, who “is never once capable of eliciting surprise.” Conversely, Attanasio, while generally dismissing “Hard Choices” as a “humdrum problem drama,” hailed McCleery for having “the charisma of a person utterly without adornment, and whatever the faults of ‘Hard Choices,’ you can’t keep your eyes off him.”

As for me, I was impressed with all of the performances, several of them quite offbeat. Director John Sayles (who coincidentally had cast McCleery in “Baby It’s You”) plays an alternately sleazy and sympathetic cocaine dealer who harbors the outlaws at his clandestine Florida lair (it’s a mystery why he doesn’t act more often). One of my favorite character actors, the late J.T. Walsh, pops up as a deputy, and the normally garrulous Spalding Gray plays a mopey, hapless defense attorney, who mangles Bobby’s case. Klenck is the real spitfire here, though, and she turns Laura into one of the more memorable female characters of the 1980s.

Unless it’s handled with a great deal of conviction (as in “Ordinary People”), there are few subject matters more boring than that of the kindly shrink helping a traumatized boy come out of his shell. Except, perhaps, for the John Grisham-esque plot of a social worker or lawyer calling for the retrial of a wrongly convicted innocent. “Hard Choices” threatens, at times, to become a sorry amalgam of both storylines; some of Laura’s speeches are didactic and obvious.

But what makes “Hard Choices” a triumph is that Laura is so unpredictable. One minute she is bawling out a halfway house aide for mistreating her client; the next, she’s snorting cocaine with college buddy Sayles, who coolly reminds her that her acts of social justice get kids “back on the street” to buy his narcotics. Her sexual attraction to the barely pubescent Bobby might seem totally implausible, but it’s supposed to be–only a crazed soul, after all, would hold a prison warden at gunpoint to spring a convict from jail, a convict she’d been publicly fighting to exonerate.

On the surface, “Hard Choices” is a familiar lamentation against a certain corruption often attributed to the rural South–widespread drug use, incompetent legal figures, unjust trials. But while it evokes both the bucolic, outdoorsmanlike spirit of the region (the trio of brothers is shown spear-fishing and hiking in the opening sequence) as well as its seedy, dreary side (the older boys engage in much dilaudid abuse, and they’re both gun nuts), it deftly sidesteps cliches. Bobby’s relatives may speak in an uneducated drawl, and some of his cell mates are the usual sordid figures (a ranting preacher, a pedophile). But King and Mickelson never turn these people into caricatures. Even the most impulsive characters have a pensiveness and intelligence about them, and the film trusts the audience to slowly take in their various flaws; it never beats you over the head with its agenda.

Those strengths compensate for some of the film’s TV movie-esque qualities (an uninspired rock music score, aside from the Richie Havens number, and some lackluster editing). It’s criminal that “Hard Choices” hasn’t received any DVD distribution.

“That’s a matter of rights, unfortunately,” said King. “Robert and I have the negative, but I don’t think we have the legal wherewithal to [release it].”

“Lorimar is no longer in business, so [the film] has gone to Warner Brothers,” said Mickelson. “It’s in their library but kind of hiding there. Unfortunately, in those days, we ended up signing away in perpetuity. The foreign rights will come back to us but not domestic, which is unfortunate.”

In the meantime, “Hard Choices” can be viewed on Amazon Instant.

Long before Pelé’s involvement with “Hotshot,” King was called in by his friend, who had worked on “Hard Choices,” to polish up the first draft of the script.

“It was financed by a Greek real estate guy, Steve Pappas,” King remembered. “I sat down with Steve and his director and my friend and another producer. I said, ‘I can polish this script, but that’d be like polishing the silver while the house burns down. This is just an awful script.'”

“Steve looks at me and says, ‘Well, what do you mean?’ And I said, “It’s about a nice kid who does a lot of nice things. That’s not a very interesting story on any level. I mean, I think it’s just atrocious. But I’ll do whatever you want.’ He said, ‘What would you do?’ I said, ‘Well, I would make the kid into an asshole. It’s not the most original idea, but…to achieve his potential, he has to learn how to love, he has to learn how to give. He has to bottom out. He starts out arrogant, he gets knocked down and then he has to rebuild himself.'”

“So Steve says to my friend, ‘I thought the script was pretty good, what did you think, Mark?’ Mark said, ‘No, I think Rick’s right, this would help the project.’ And the director says, ‘Yeah, I think Rick’s making a lot of sense.’ Steve looks at them and says ‘Well, why didn’t you tell me?’ In my own mind, I’m thinking, ‘Because you’re paying them, Steve!'”

“So they put me in a hotel,” King continued, “and I started churning out pages. Pelé wasn’t even in the script yet. They hired a director who got fired, then another one got fired, and then they got Pelé, and then they called me to finish the film. It was definitely not one of the greatest films in the world. But for some reason it was very popular in China.”

The shoot was still frenetic and disorganized when King stepped in. His first day on set, he was assigned a diner scene…that hadn’t been written yet! “I sat down with a yellow legal form and I wrote the scene, with 40 people watching,” he laughed.

But there were some perks to the project. King enjoyed being flown later on to Brazil, to shoot the (rather offensive) storyline of Pelé, playing a retired version of himself, living a hermetic life in the jungle (oh, those primitive South Americans!)

As requested, the lead character was changed from nice to cocky. As played by Jim Youngs, he is just about unbearably cocky, the spoiled brat son of a shipping magnate who yearns to play professional soccer, against his snooty father’s wishes that he attend college and join the family business. Yes, there’s also a snooty girl (the daughter of another magnate) that his parents want him to marry. In the funniest scene, Youngs snubs the girl, his parents lecture him (“You’re going to college, and that’s final!”), he mouths off (“I’m playing ball, and that’s final!”) and, with pounding hard rock in the background, gets a cold hard slap to the face from Dad.

Anyway, Youngs travels to Brazil to find his idol (Pelé), and spends a lot of time pleading to be trained by him in all things soccer. In Mr. Miyagi-like fashion, Pelé at first refuses, but it isn’t long before the two are jogging through Brazilian jungles and beaches, with Youngs giddily straddling Pele’s able back (I’m not sure how that particular exercise helped Youngs get into shape, but never mind).

Back at home, Youngs goes through the usual sports movie highs and lows. He’s too proud and cowardly to admit he comes from money, so he lies that he’s poor, to fit in with the tougher, mostly Rastafarian teammates. He spars with the coach, who berates him for his bad attitude. When he gets declared an all-star, he gets even more arrogant, buying hideous polyester suits and flirting with the press. Then he has a dark moment of the soul when his best friend ends up in a wheelchair.

Punctuating all this is a romantic subplot with then-upstart Penelope Ann Miller, which is all but forgotten in the second half (possibly because, according to King, Miller and Youngs hated each other) and lots and lots of soccer. If you’re a die-hard soccer fan who likes your sports films very formulaic, “Hotshot” is the movie for you; for everyone else, it’s almost worth it just to watch Youngs get slapped.

“Hotshot” can be found on Amazon.com, but beware of third-rate bootlegs; the title on mine was misspelled as “Hotshots.”

After the Fall 1987 release of King’s “The Killing Time,” a decent tale of double-crosses and piled up bodies in small-town California, starring Beau Bridges, King was presented with “Forced March.” The production mirrored reality in several ways.

After the Fall 1987 release of King’s “The Killing Time,” a decent tale of double-crosses and piled up bodies in small-town California, starring Beau Bridges, King was presented with “Forced March.” The production mirrored reality in several ways.

Its star, Chris Sarandon, had been mostly relegated to smirking villain roles, like the arrogant romantic foil in “The Princess Bride” and the dashing vampire in “Fright Night.” By 1988, he wanted to sink his teeth into more serious parts, and so King assigned him to play…an actor yearning to sink his teeth into more serious parts! The opening scene of “Forced March” seems to imply that the film will be an uproarious comedy. Sarandon is the lead on a schlocky TV action show; his contract stipulates that the character must explode at the end of the season but miraculously be put back together at the start of the next one. That’s a whole other movie waiting to happen! But in the somber “Forced March,” Sarandon, fed up with such foolishness, signs up to play Miklós Radnóti, a Hungarian Jewish poet and eventual prisoner killed during the Holocaust.

While researching the role, Sarandon’s character, a Jewish American, finds out that his father was a Holocaust survivor but that his mother was not so lucky. King related to the story because of his own revelation–albeit a much less shocking one–that he was a quarter Jewish, which he discovered when he was 21. “I come from the most rigorously WASP background you can imagine,” King told the New York Times in October 1989, when “Forced March” began a short New York City theatrical run. “I’m not really Jewish, but Jewish enough that I could have been shot during World War II.”

Shot on location in Budapest, “Forced March” switches between two narratives. Radnóti’s story is told, rather straightforwardly, in the film within the film. He refused to leave Hungary even during a time of great peril. He continued, bravely, to write poetry about the dissolution of his beloved country. When hatred against Jews reached a turning point in Hungary, he and his wife converted to Catholicism. His identity was still known, though, and he was forced to join an inferior, unarmed battalion, which, upon Hungary’s defeat in 1944, was transferred to a mining camp in Serbia. When Yugoslavian Partisans approached, he and thousands of other Jews in his battalion were force-marched back to Hungary; Radnóti was killed during the journey.

The other part of “Forced March” concerns Sarandon’s straining to understand this complex man. He pores obsessively over Radnóti’s poetry, and meets with his wife, but still can’t comprehend why Radnóti didn’t actively fight the Nazis when he had the chance. When he tries to play the character as more violently heroic, the apoplectic director (John Seitz) barks at him. Whenever Sarandon isn’t brooding, he’s romancing his pretty co-star (Renée Soutendijk) in attention-getting settings (Budapest’s stunning Gellért Hill, overlooking the Danube; a steamy Turkish bath; a New Wave rock club with topless dancers).

“Forced March” is a good-looking film, and parts are powerful. The normally bland Sarandon gives a wrenching performance. But towards the second half, Sarandon and Seitz’s head-butting becomes a little repetitive. And the script is on the taciturn side. As Vincent Canby noted in his review, the film “meditates upon a number of topics but is never very articulate.”

That said, the film is notable for being King’s most ambitious work, likely the one that inspired his later documentary on war and poetry. It certainly should be distributed on DVD (as of yet, it is only available on VHS).

King himself has mixed feelings about “Forced March.” “Some of the present-day story is not that strong, but some of the stuff in the past is very powerful and I’m really proud of it,” he said.

Shooting in Communist-controlled Budapest, a year before the fall of the Berlin Wall, was far from easy, but King wasn’t put off by the experience.

“There was a lot of bureaucracy and a certain amount of disorganization and corruption,” King remembered. “The party guys knew things were coming to a halt and they were very smart. I remember talking to one of the costume people, and she said, ‘Rick, they’re stealing so much!’ I said, “If you take how much the producers are spending here, and add to that the amount being stolen, it’s still [costing] much less than it would in the US or France.'”

He recalled one darkly amusing story from the shoot. “We had gotten these tanks, the real German tanks. We shot a scene where they were coming down the street. The same day, we shot in this apartment building, and there was an old tenant named, I think, Mrs. Schwartz, and Jews still get discriminated in Hungary. She thought the Nazis were back! She was standing at her bus stop with her suitcases, and the location manager said, ‘What’s going on?’ And she said ‘They’re back!’ She didn’t fuck around! She packed her bags and hightailed it out of there.”

What genius substance was Rick King snorting when he came up with the following simple, easy-to-pitch idea for a summer blockbuster: Johnny Utah, a highly unlikely, bonehead Los Angeles FBI agent, is investigating a series of robberies, perpetrated by four or five men who call themselves the Ex-Presidents (they wear exaggerated face masks of Carter, Reagan, etc.) On a whim, he suspects these robbers are surfers. He goes undercover. To pass as a legitimate surfer, he gets trained by a pretty girl who sort of looks like him (only not quite as pretty). He finds out the lead surfer is a shaggy-haired Buddhist named Bodhi, who despite his proclaimed “hatred of violence,” is a lean, mean martial arts expert and a skilled marksman, to boot. The agent becomes enamored of this group of outlaws, as they turn him on to the adrenaline rush of surfing, sky diving and, yes, bank robbing. (Along the way, there’s a fun little fight wherein Red Hot Chili Peppers frontman Anthony Kiedis gets shot in the foot). But things get ugly when Utah’s older, more cynical partner, a Vietnam vet who’s on (you guessed it) his last case before retirement, takes a fatal shot to the heart. Now it’s revenge time!

Despite what us “Point Break” enthusiasts might think, the genesis for the story idea was rather commonplace. Sometime during the late 1980s, King read a newspaper article about bank robberies.

“Los Angeles at that time was sort of Bank Robbery Central, because you could rob a bank and then jump on the freeway,” he said. “So there was a huge bank robbing problem, which is of course an FBI thing. And then I was sitting on a beach in Malibu, learning how to surf, and I’d just gotten out of the water. And I thought, ‘Surfers who rob banks. And a FBI agent that’s a good athlete that goes undercover among those surfers.’ It just made a lot of sense and everything just flowed from that. It wasn’t that original an idea, there’s only like ten ideas. The guy undercover ends up liking the guys he’s trying to bust more than who he’s working for. I always thought of it as ‘Tom Cruise Joins the FBI.'”

King shared the idea with Peter Iliff, who received screenwriting credit. It was not King’s idea, he admits, to have the robbers dress like presidents, nor for their leader to be a practicing Buddhist, but he did write the final scene (some of its dialogue is cited in the photo captions above). The film sat for some time and was then “yanked” by Ridley Scott.

“He spent as much in pre-production as I spend on a film, and then decided not to do it,” said King. “It languished for two or three years, and then James Cameron loved the script and wanted to sponsor Kathryn Bigelow, who was either his wife or girlfriend back then.” It was released in the summer of 1991 with Keanu Reeves as the agent, Patrick Swayze as Bodhi, Gary Busey as the snarling older partner and Lori Petty as the cute Reeves lookalike.

“Bigelow is obviously a really good director, but not that strong with character, so that could have been a little better,” King said. “And I thought the surfing sequences were not that good. They could have really knocked it out of the park. It was obviously made by someone who wasn’t a surfer.”

Surfing details weren’t the only original script qualities that got lost in the shuffle.

“The Gary Busey character was supposed to be Greek,” said King. “There was all this stuff about his cooking. I wish that had been played through a little more, but it’s hard to sell Gary Busey as a Greek!”

Though less than thrilled with the final product, King made out pretty damn well financially from “Point Break,” especially given that he only received story credit.

“The first few years after the film was made, that would sometimes result in $30-40,000 a year in residuals,” he said. “I’m sitting right now in a house that it paid for.”

An insanely over-the-top hybrid of “Children of the Corn” and “Blade Runner,” centered around the early-1990s fad of rollerblading, “Prayer of the Rollerboys” is one of the most deliciously campy films I’ve ever seen. Despite being somewhat of a cult phenomenon, it is not available on Netflix, though it can be viewed in its entirety on YouTube.

An insanely over-the-top hybrid of “Children of the Corn” and “Blade Runner,” centered around the early-1990s fad of rollerblading, “Prayer of the Rollerboys” is one of the most deliciously campy films I’ve ever seen. Despite being somewhat of a cult phenomenon, it is not available on Netflix, though it can be viewed in its entirety on YouTube.

Set in the distant future, “Rollerboys” presents a dystopian Los Angeles that’s been overrun by the title gang, a pack of fascist rollerblading youths in grey overcoats with patched-on crosses (a nod to the Ku Klux Klan?) who tend to skate in swishy, slow-motion unison. Their leader, Gary (played by Christopher Collet, a normally matter-of-fact actor who here sports a ridiculous mop of blond jheri curls and sneers at the camera), makes regular TV appearances where he beckons, in true evangelist style, for people to join his Cause.

As in many films aimed at teens, parents are nowhere to be found. That’s because, as Gary explains it, they lost their foreclosed-upon homes after their greedy investments sank them into massive debt, and died in futility. Now the country is run by “alien races,” specifically the Japanese, who have, among other dastardly deeds, bought Harvard and shipped it to the Far East. (The film was, oddly enough, financed by three large Japanese companies, despite their country being portrayed as an evil superpower; maybe they were secretly happy that America was portrayed as weak).

As in many films aimed at teens, parents are nowhere to be found. That’s because, as Gary explains it, they lost their foreclosed-upon homes after their greedy investments sank them into massive debt, and died in futility. Now the country is run by “alien races,” specifically the Japanese, who have, among other dastardly deeds, bought Harvard and shipped it to the Far East. (The film was, oddly enough, financed by three large Japanese companies, despite their country being portrayed as an evil superpower; maybe they were secretly happy that America was portrayed as weak).

Meanwhile, Los Angeles is a squalid wasteland where scores of homeless druggies camp out in abandoned, fenced-off industrial lots, and where the only employed folks–besides the drug dealers, who peddle an extremely potent substance called Mist, and a few incompetent, corrupt police officers–are pizza delivery boys.

One such pizza boy is Griffin (Corey Haim), a kick-ass rollerblader whom the Rollerboys try, in vain, to recruit. The Rollerboys are far angrier at the (mostly black) junkies on the street than the “alien races” they purport to be offering salvation from (in fact, they work covertly with the Japanese to produce a deadly poison, disguise it as Mist, and kill off the druggies). Their smirking, often racist rhetoric doesn’t work on Griffin, who’s loyal to the obligatory Wise Old Black Man character (here named Speedbagger), but it does seduce his thoroughly obnoxious, pony-tailed little brother into joining the gang.

To save his sibling, Griffin is forced to go undercover, aided by Patricia Arquette as a pretty blonde undercover cop/rollerblader, with whom he engages in plenty of finger-sucking foreplay but no sex. It turns out that, despite their “Just Say No” diatribes against drugs and hedonism, the Rollerboys throw some pretty wicked parties. In the funniest scene, Griffin and his brother attend one such bash in a warehouse outfitted with a kiddie pool (in which two half-naked women oil-wrestle), a macabre merry-go-round and several prostitutes in cabaret regalia. (This scene also introduced audiences to Nine Inch Nails’ “Head Like a Hole.”)

Things get decidedly uglier when Griffin is subjected to the Rollerboys’ “initiation” process. He and a few other rollerblading pledges race, illegally, through a private industrial parking lot, narrowly escaping all sorts of gunfire. First, teams of security guards chase and shoot at them for trespassing; if they survive, Gary and his cronies, waiting at the finish line, fire rocket launchers at them from the back of an open truck. Haim somehow dodges these obstacles and reaches Collet’s truck first; the sole remaining skater survives but loses the race. Collet promptly shoots the other racer in the head as they drive off. “Rules are rules,” he chuckles.

“Rollerboys” is loaded with similarly absurd sequences. My personal favorite: during the climactic battle between Collet and Haim (who, coincidentally, played brothers years earlier in the drama “Firstborn”), a gas barrel explosion sends Haim somersaulting through the air, in slow motion. He emerges completely unharmed seconds later, spry enough to swing around a pole–on rollerblades–and fly-kick Collet in the face.

There are plenty of thriller cliches (the villain menacingly stroking an iguana, the villain menacingly cooing the hero’s name to get him out of hiding in a warehouse). But “Rollerboys” is never boring. It is a decadently moronic piece of trash–surely how King and crew intended it to be–and its Netflix debut is much warranted.

King’s on-set stories about “Rollerboys” are almost as entertaining as the film itself. Though Haim, then 19, could be a dedicated performer–King confirmed industry reports that he did most of his own stunts in “Rollerboys”–the star was quite drug-dependent during filming, which led to some maddening altercations. Still, King retained a protective fondness for him.

“During Chris’ death scene, he suddenly decided he had a stomachache and said ‘I gotta go,'” King remembered. “I said, ‘No, you can’t leave someone during their death scene. We started the scene.’ He said, ‘You can finish it without me,’ and I said, ‘No, you’re gonna stay, you’re gonna do this goddamn scene!'”

“So we had [screenwriter] Peter Iliff drive out, and he blocked Corey’s car. Corey was furious, and he storms into the production office, and he calls his doctor. He talks to him and says, ‘So you think I’m OK?!’ and slams the phone down. He says, ‘Get me another doctor!’ So he and his bodyguard call another doctor who says Corey has a stomachache, and I said, ‘Corey, you know we’re just gonna wait this out, buddy. Your little tummy’s gonna get out of here faster if you get back out on the set.’ So he did the scene and was fine.”

The hypochondria didn’t end there.

“One time he said he had a heart attack, and it was just an anxiety attack,” said Robert Mickelson, who co-produced “Rollerboys.” “If someone says they’re sick, even if you aren’t sure, you have to take them at their word. The last thing you want is to have someone die on the set. But in the end he came through for us.”

“Corey would always say, ‘Rick is the only person that says no to me,'” King continued. “We had that kind of relationship. I always wanted the best for him. I always thought he was talented. He had a shitty upbringing. His parents were very manipulative. A friend of mine was one of the camera guys on ‘The Lost Boys,’ and he used to let Corey sleep in his room sometimes because Corey’s dad was using Corey’s room to bang a groupie.”

“He wasn’t, honestly, that accomplished,” said King. “He wasn’t that deep a person. And he could hardly read. He was reading books in rehab that were for seventh graders. But he was a sweetheart, when he wasn’t being kind of bratty.”

Haim and King’s friendship continued up through the darkest days of his addiction.

“The last time I saw him, it was terrible, he must have been 50, 75 pounds overweight,” King recalled. “He was thinking of doing a sequel to ‘Rollerboys’ and at that point he was in his thirties!”

Haim died from pneumonia on March 10, 2010, at the age of 38.

While working with Corey Haim may not have been a walk in the park, it was heavenly compared to King’s experience with Sasha Mitchell on the Brazilian set of “Kickboxer 3: The Art of War.” The film (which is available on Netflix) is pretty much exactly what you’d expect; the behind-the-scenes stories are far more interesting.

“The guy was a nutjob,” King said plainly. “The crew hated him and liked me. One of the grips was a cop, and he said, ‘If that guy ever touches you, I’m gonna arrest his ass and throw him in the nastiest Brazilian jail you’ve ever seen.'”

“He would just lose it,” King continued. “It sounded familial, because he told me his father would be sitting at the table one minute, the next he’d say ‘I don’t like this’ and throw his plate against the wall.”

“One day, he was so mad at me, and he’s a pretty big guy and I’m small, I’m under 5’7. He said, ‘I just feel like punching you the fuck in the face,’ with his fist right next to me. And I said, ‘Do it, man. Right here on the cheek. That’ll be a million dollars. Hit me twice, that’s two million dollars.’ You just have to try and have a sense of humor.”

“Another time, I’d just had it with him. He said ‘This is a stupid line!’ And I said, ‘Sasha, you wouldn’t know a good line if it was right in front of you.’ He was so hurt. He said, ‘How could you say that in front of the crew?’ I was like, wasn’t it a couple of days ago you were threatening to knock my head off?”

Mitchell (whom I unsuccessfully tried to interview a few months ago about his experience working with Paul Morrissey) reportedly did his own kickboxing in the film, which King said resulted in several nerve-racking situations.

“We had some sequences where you don’t have to really kick the guy,” said King. “And he kicked the crap out of this guy. I said, ‘What are you doing? It’s not gonna be any more real, because we’re shooting from behind. We’re not seeing where the kick hits.’”

I asked King if perhaps Mitchell was acting out to shed the squeaky-clean persona he’d obtained from starring in the cutesy sitcom “Step by Step.”

“I think he thought people thought he was stupid, which was true,” King replied. “And he was also violent, and so he used his position of privilege as the star in a very negative way.”

“Quick,” which undeservedly went straight to cable in 1993, is King’s slickest film, and probably his most entertaining from start to finish. It’s a convoluted thriller in the vein of “La Femme Nikita” (female assassin with a heart of gold goes through many costume and wig changes) and “Something Wild” (unhinged woman liberates uptight man). But Teri Polo’s knockout performance as this tough-talking pixie makes up for the story’s lack of freshness, and she’s the perfect romantic foil for Martin Donovan, playing a stuffy accountant whom she takes hostage. It’s also nice to see an action heroine who does look disheveled after a death-defying fight, rather than all made-up and well-coiffed (in fact, Polo looks sexiest when disheveled).

“Quick,” which undeservedly went straight to cable in 1993, is King’s slickest film, and probably his most entertaining from start to finish. It’s a convoluted thriller in the vein of “La Femme Nikita” (female assassin with a heart of gold goes through many costume and wig changes) and “Something Wild” (unhinged woman liberates uptight man). But Teri Polo’s knockout performance as this tough-talking pixie makes up for the story’s lack of freshness, and she’s the perfect romantic foil for Martin Donovan, playing a stuffy accountant whom she takes hostage. It’s also nice to see an action heroine who does look disheveled after a death-defying fight, rather than all made-up and well-coiffed (in fact, Polo looks sexiest when disheveled).

Donovan is in debt to some mafiosos/crystal meth peddlers. Quick (Polo) is their key hitwoman. On the side, she’s dating a vicious, bent cop (Jeff Fahey), who puts Donovan under witness protection after he steals $3 million from the dealers. Quick is hired to bring the accountant back to the mafiosos; the cop, who knows the accountant’s whereabouts, wants her to secretly retrieve the stolen money and take off with him. Instead, she takes Donovan hostage, initially to get the cash but eventually (when she, of course, turns soft on the big lug) to protect him from the bloodthirsty dealers and the cop. The double-crosses and bodies pile up. Tia Carrere shows up and gets shot. There’s a cute scene where Polo feeds KFC to a handcuffed Donovan.

“Quick” wouldn’t work if the sparks didn’t fly between Donovan and Polo and miraculously they do, even though, according to King, the two actors did not get along very well.

“Martin is very methodical, whereas Teri Polo…she’ll be making a joke about two chickens at the bar, you shout ‘Action,’ and she just turns around and is right into character,” King explained.

“Quick,” which is a perfect popcorn flick for a rainy night, is available on DVD but not on Netflix.

While the “Basic Instinct” knock-off “A Passion to Kill” plays like a straight-to-Cinemax cheesefest (hunky doctors, beautiful women turned on by knives, sex scenes in sprawling mansions), it actually received a brief, nationwide theatrical run in late 1994. There must have still been high demand for “Quantum Leap” star Scott Bakula.

While the “Basic Instinct” knock-off “A Passion to Kill” plays like a straight-to-Cinemax cheesefest (hunky doctors, beautiful women turned on by knives, sex scenes in sprawling mansions), it actually received a brief, nationwide theatrical run in late 1994. There must have still been high demand for “Quantum Leap” star Scott Bakula.

He plays a shrink who’s smitten with his best friend’s new, sultry wife (Chelsea Field), who, we know from the opening sequence, stabbed her mean former husband after a quarrel years ago. Ignoring the advice of his still-hurting ex (Sheila Kelley, the strongest performer here), he embarks on an affair. Then one night his friend turns up dead, of an apparent stab wound. Field swears she is innocent. He wants to call the police. “No,” she responds. “I was involved in a stabbing long ago.” A few minutes later, Bakula and Field are pawing at each other in her car, as she tantalizingly runs a knife over his hairy chest.

More bodies pile up, but whodunit? Field? Bakula’s jealous ex, trying to frame Field? Field’s vengeful ex-husband, still bitter about that stabbing episode? Bakula finds out when he hides from the killer in his bedroom; the killer, thinking he is in the bed, stabs it repeatedly with a knife. Feathers fly.

Despite many scathing reviews, “Passion” isn’t bad enough to be unintentionally funny. It’s pretty run-of-the-mill, probably because, no matter how boneheaded the script gets, King’s direction stays competent. (He is not one to condescend to the material). There is one foreshadowing howler, though, that will go down in history. When Bakula meets Field, and coyly tells her to quit cigarettes, she says, “There are a lot worse ways to die than smoking.”

King wasn’t crazy about the film himself. “Of any of the films I made, that was the one where I felt a disconnect with the script, which we [tried to] sail over. I don’t think it completely works. I never quite got a handle on Chelsea’s character. Her character felt like a movie character. Hmm, why is she doing that? Because it works for the movie!”

“Passion’s” sex scenes are fairly erotic, which makes sense since Bakula and Field struck up an off-set relationship and are still together today, with two children. The near-sex scene with the stunning Kelley is even more enticing. King informed me that Kelley is now teaching professional pole dancing!

The film is available on VHS, and a no-doubt bootlegged DVD is now sold on ioffer.com.

King’s last three fiction films were “Terminal Justice,” a throwaway 1995 thriller about cybersex-related murders; the Florida-set 1997 murder-mystery “Catherine’s Grove,” starring Jeff Fahey and Maria Conchita Alonso; and “Road Ends,” released the same year, about an escaped but innocent convict hiding out in a small town. Of these three, only “Catherine’s Grove” is unavailable on Netflix; it has yet to even be released on DVD.

The film was written by two married Florida real estate lawyers, Tony and Robyn DiTocco. Tony told me via e-mail that they intended to finance it with their life savings of $250,000. After meeting actor James Hong at a local seminar, the couple was introduced to King, who suggested the budget be raised to attract well-known talent. That budget eventually climbed to $2.2 million after the DiToccos privately raised $750,000 and hooked up with a distributor and investment bank. By the time of the film’s completion, the distributor had gone out of business, “so Robyn and I made 12 prints, convinced the local movie houses to rent us some screens and sponsored our own theatrical release, which finished second in the South Florida market opening weekend. After that, we ran out of steam and money, and because we had no way to generate enough revenue to pay back the bank, we gave them back the film.” (The DiToccos’ only project since was the little-known Dylan Walsh comedy “Chapter Zero,” released in 1999, though they have considered getting back into film production.)

“Catherine’s Grove” is a decent thriller, if a bit over-the-top with plot twists. Part of the film has to do with unsolved murders, mostly of transvestites. A ball peen hammer-wielding hand is shown reaching towards the victims, but mercifully, most of the gore is kept off-camera. The rest of the plot involves the disappearance of a woman named Catherine. The sleazy, cigar-smoking, Hawaiian shirt-wearing police officer (Fahey) and his sassy partner/girlfriend (Alonso) are assigned to both cases, and keep hearing conflicting stories about Catherine. Her creepy brother, who likes to cross-dress, thinks Catherine was buried alive by their supposedly sadistic uncle (Michael Madsen). The uncle says Catherine died years ago, after falling from a tree-house. (I won’t ruin the ending, but let’s just say that if you’ve seen “Color of Night,” you’ve essentially seen “Catherine’s Grove.”)

King said he originally offered Corey Haim the role of the cross-dressing brother. “He would have looked really good as a girl,” he said. “We brought him down for a test and he just flipped. He was so drug-dependent at that point. The role freaked him out.”

In an excellent April 2011 Sound on Sight article partially profiling King, he said he loved the creative freedom he received when making direct-to-TV films like “Grove.” That industry, he bemoaned, began to dry up by the late 1990s, when large studios started to build their own independent wings, which direct-to-TV distributors could not compete with.

As with most artists, King has had his share of bad breaks. But the only moment during our discussion where he seemed even remotely distraught is when I brought up “Traveller,” the 1997 crime drama originally slated to be directed by King and then taken over by star/producer Bill Paxton.

As with most artists, King has had his share of bad breaks. But the only moment during our discussion where he seemed even remotely distraught is when I brought up “Traveller,” the 1997 crime drama originally slated to be directed by King and then taken over by star/producer Bill Paxton.

“Robert Mickelson and I had gone after Bill Paxton, and then Robert really liked the idea of [casting] Val Kilmer and dropped Paxton,” King recalled. “When Paxton got some heat and came back into the project, I think he was pissed at us. He wanted Jack Green to direct, who’s a good cameraman but, frankly, not a very good director. So he replaced me. There wasn’t much I could do. They treated me very well financially.”

Losing control of the project wasn’t what rankled King. It was a key change in the storyline that had most interested him about Jim McGlynn’s script in the first place.

“The original script is about the relationship between the traveler, Bill Paxton, and the girl he meets. There was this whole thing where, when the badguys come, the guys he’s double-crossed, he’s helpless, and she faces the guys down and saves his life. It really makes it clear that he totally owes her and also makes her character strong. It was a great scene. And Paxton changed it because he had some buddy, Luke Askew, that he wanted to have involved. So he just brings this guy in to save the day. I said, ‘I know he’s your buddy, but that cuts the whole point of the film out.’ It was a really good woman character and now she’s just sort of there. Linda Hamilton was gonna play it and then when they made that change, she said ‘Fuck you!’”

Paxton attempted to keep relations with King friendly, but King, as well as Mickelson, felt it best to walk away from the project, though both were credited as executive producers.

“I understand why Paxton acted the way he did, but I just didn’t feel like being his pal,” King explained. “If I think things have gone south, I prefer to disassociate. I like Paxton. I think he’s a good actor and a good guy. That’s just my reaction to things. If it’s a film I want to develop and direct, I don’t want to be around as a producer and offer advice and smooth over problems with the actors. I’m just not interested. I like to make movies. I’d rather make five movies in two or three years than sit around and wait to make the perfect one.”

Since 1997, King has worked mainly in television, directing and producing history films and nature shows. But he still has a few fiction ideas he’d like to get off the ground.

“I wrote a script, around 1994, about Sherlock Holmes in the present day. He’s a surfer who lives in Venice Beach, and Watson is a Latino nursing student, and they live together. Holmes has a serious crack addiction problem. I tried to sell it as a feature and it was a little raw and hard-edged, and Peter [Iliff] was able to engineer a sale to ABC for a television series. We did a pilot and then they didn’t pick it up. And now we have ‘Elementary,’ which is kicking butt.”

The interview, happily, inspired King to attempt to get some of his prized older films released digitally. Asked why he hasn’t launched that effort already, King replied, “I haven’t been terribly good about keeping track of these things. I’ve sort of dropped the ball because I’m running around chasing sharks.”

Sensational, as I expected, Sam! I always wondered how come PRAYER…got the green light, since some four years earlier another sci-fi actioner with kids in rollers sunk at the box office (the Mel Brooks-produced SOLARBABIES).

-I always wondered if the PAPPAS character in POINT BREAK was some sort of ´jab´ at the real-life producer of HOT SHOT (by the way, though I haven´t seen the Pelé vehicle in ages, I do not recall anything closer to a jungle in the movie than some sorte of bushy New Orleans-like area).

-GROVE´s is a cool southern gothic neonoir indeed…cool you got the talented Rick King to talk a bit about the movie.

-By the way, I´m stealing your ´sex scenes in srawling mansions´ comment someday.

Just watched ROAD ENDS, enjoyed it very much.

Pingback: Comida para peixes: Os filmes desconhecidos de Pelé | O Poderoso Chofer

I don’t care about this, i quit my day job and earn money online, around $2800/month, how?

Just search google for – rilkim’s tips

Hello Rick, Jeffrey Postel here, of “Jeffrey”, 1971. Can we talk? 978 309 8531. Thanks, Jeffrey

Kickboxer 3 is on TV in Rio de Janeiro this week. I play the man who sells them guns, and look quite in control doing it.

Pingback: These 23 Secrets About Point Break Are a Total State of Mind - Times Of Digit USA

Pingback: These 23 Secrets About Point Break Are a Total State of Mind – E! NEWS – USA SPOTLIGHT

Pingback: Is Point Break Based On A True Story? - Techtwiddle

Pingback: USA UP ALL NIGHT MONTH: Kickboxer 3 (1992) – B&S About Movies