I’m starting a new section on this blog called “New York Times Slights,” honoring filmmakers whose movies–most of them small-scale–were unfairly given short shrift by the legendary paper.

Bad reviews come and go, but vague bad reviews are another thing altogether. To date, the paper’s most dismissive/snobbish reviews came from the late Vincent Canby, who reigned as chief critic from 1969 to 1994 (unsurprisingly, many second and third-string critics during his tenure followed suit). It is not uncommon to read a one-paragraph, barely 100-word Canby review in which not a single performer is mentioned, in which no plot is discussed or–most perplexing of all–in which no specific reason for finding the film bad is listed. This is a what a typical Canby-esque short pan might sound like (with only slight exaggeration): “XYZ is a film of monumental ineptitude. It is as listless a film as I can imagine. It features many actors who have been used to better purpose elsewhere. It opens today at ABC Theaters.”

Some might read such a review not as unjust, but as a mere result of space limitations–i.e., more space was devoted to larger, more popular films opening the same day. Others might even read it as merciful: the critic, finding no value in the film, would rather not pontificate in cruel detail on why the film, to him, was such a failure. A Pauline Kael-esque five-column rant might be more damaging to the filmmaker’s ego or the film’s theatrical run.

The undeniable truth, though, is that a long pan makes it clear the film, however poorly regarded, got under the writer’s skin, and was deemed worthy of a point-by-point takedown. A short pan, to me, is impossible to read without picturing the writer’s nose in the air. It is the equivalent of the condescending chuckle, the shooing away of a fly–the quintessence of “you mean nothing to me and my mind has moved on to more important things.” Short pans are a special brand of brutal, and if the film is small/independent and badly in need of any publicity, the brutality is compounded.

When I read such reviews, I am left deprived of so much information that I am all the more curious to see the film and determine what inspired such a cold shrug-off. (Unfortunately, especially regarding small films, this is rarely the mindset of most moviegoers or even most movie review readers, who are often apt to leave such films alone). My reactions to the films themselves have varied–sometimes I really like them and am puzzled by any negativity; sometimes I agree the film is deeply flawed but still worthy of some degree of analysis–but rarely do I agree with the critic that it deserves such a minimum-effort brush-off.

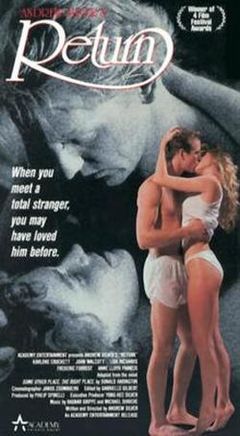

I am starting this series with Andrew Silver’s “Return,” which, like countless other films, received this harsh treatment. It is based on a novel by Donald Harrington called “Some Other Place. The Right Place,” and it is part family melodrama, part romance and part supernatural fantasy. Karlene Crockett plays a young Arkansas woman traveling cross-country with a friend; after her car breaks down in Pennsylvania, she reads a newspaper item about a paranormal medium and her client, a man claiming to be Crockett’s long-dead grandfather. The grandfather was shot to death during one of Crockett’s early childhood outings with him, and she never knew why. She meets the man (John Walcutt), watches–and fully buys–his transformation, under hypnosis, into the grandfather, and then takes him to her grandfather’s hometown in Massachusetts, hoping that key memories will come back to him. Meanwhile, her father (Frederic Forrest) is running for public office and doesn’t want any secrets coming out about her grandfather’s past, which involved her mother and which, apparently, are sordid. Predictably–yet still somewhat creepily–a chaste love affair develops between Crockett and Walcutt, and a strange climactic standoff unfolds at an Arkansas waterfall–the same site of her grandfather’s murder.

Plot-wise, “Return” is a little hard to swallow. This is true of both the theatrical release, which I saw on a VHS version via Amazon, and which includes a rather jarring incest subplot, and the edited-for-TV version that Silver sent me, which excises the incest angle. It is a supernatural film devoid of special effects, as it was made on a shoestring budget, and so the hypnosis sequences mostly consist of Walcutt swirling his head around. Though set in three states that are rather far from each other (Pennsylvania, Massachusetts and Arkansas), characters seem to get from one place to another improbably fast (in one very impressive sequence, though, a long-distance road trip is shown in rainy, sped-up time-lapse, to a jaunty, percussive score).

That said, the film is very pleasant to look at, with almost every scene staged amid a lush, panoramic, autumnal backdrop. The acting, for the most part, is superb. Silver also manages to wring eroticism from what could have been a very squirm-inducing romance.

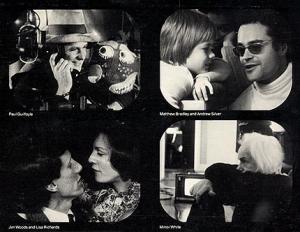

I tracked down Silver and he sent me the edited “Return” on DVD, which also included two of his 1970s made-for-public-television films: “The Murderer,” a surreal, anti-technology rant adapted from Ray Bradbury’s short story; and Kurt Vonnegut’s “Next Door,” featuring a young James Woods, about a kid who eavesdrops in horror on his neighbors’ violent domestic argument. (Some of Silver’s other television films are available online or at public libraries; some are sadly out of print).

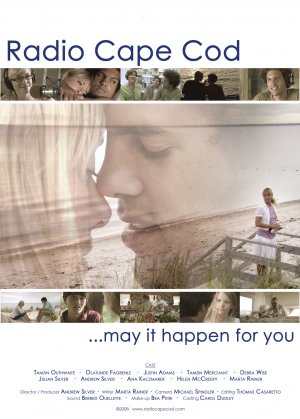

He also sent me a Vimeo link to his recent film “May it Happen for You,” an omnibus of short films about several generations of the same Massachusetts and UK-based family. Silver decided to edit his last feature-length film, the dreamy 2008 Cape Cod yarn “Radio Cape Cod,” into a single chapter in this anthology. I have seen both the full-length and truncated versions, and with the exception of a few poignant scenes between a nervous, betrothed couple, most of what’s missing are sappy music montages and countless shots of the many promontories and beaches that line Cape Cod. Silver also cut a subplot featuring him, as a New Age-y slow food chef; how’s that for modesty? (For the record, this film, and other sections of “May it Happen,” stars two rather popular British actresses, both named Tazmin! What are the odds?)

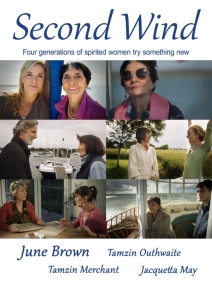

My personal favorite chapter in “May it Happen” is “Second Wind,” which is mostly about an elderly woman reconciling with her daughter and befriending a younger, aspiring writer. I also enjoyed the DVD he lent me of “Profiles in Aspiration,” a short documentary about female athletes, ranging from aspiring Olympians to Irish folk and tarantella dancers.

Silver’s fiction films are not, by any stretch of the imagination, for everybody. Silver hails from the theater, and prefers two and three-character scenes, with mostly warm–as opposed to conflict-laden–outcomes. He certainly has a knack for visuals–his bucolic or seaside settings, while curiously uninhabited, look rich and inviting on-screen, and he’s working on a virtual reality film at the moment–but the content can feel frustratingly cut off from reality, at times. For instance: in “Radio Cape Cod,” though several of the oceanographer and scientist characters talk of how swamped they are at work, they seem to constantly be taking idyllic walks on the beach or nuzzling with equally attractive, equally effusive partners. Everyone talks constantly of love, be it requited, unrequited or spiritual. And everyone talks in a sort of zen, eco-friendly patois: a wedding officiant delivers a paean to the glories of mud, a woman consoles her lovesick daughter by comparing men to mollusks, etc.

Silver’s fiction films are not, by any stretch of the imagination, for everybody. Silver hails from the theater, and prefers two and three-character scenes, with mostly warm–as opposed to conflict-laden–outcomes. He certainly has a knack for visuals–his bucolic or seaside settings, while curiously uninhabited, look rich and inviting on-screen, and he’s working on a virtual reality film at the moment–but the content can feel frustratingly cut off from reality, at times. For instance: in “Radio Cape Cod,” though several of the oceanographer and scientist characters talk of how swamped they are at work, they seem to constantly be taking idyllic walks on the beach or nuzzling with equally attractive, equally effusive partners. Everyone talks constantly of love, be it requited, unrequited or spiritual. And everyone talks in a sort of zen, eco-friendly patois: a wedding officiant delivers a paean to the glories of mud, a woman consoles her lovesick daughter by comparing men to mollusks, etc.

But like Silver himself, the movies are so gentle, so positive, they’re pretty much impossible to dislike. And they’re so filled with good will that you can ignore the often nagging soundtrack (lots of synth fretless bass and synth tuba and flute). It would not be surprising to find a collection of Silver’s films at, say, a cozy bed-and-breakfast or a seaside inn. They are movies whose settings are so pretty and whose messages are so pristine that, watching them, you wouldn’t feel like some cynical couch potato, shrugging off outdoor living. He transports you to a place of spiritual fulfillment.

I had a chance to meet with Silver a few weeks ago in New York City, near his favorite midtown theater on East 59th Street. Following are excerpts from that conversation:

Sam Weisberg: I just saw Karlene Crockett, the lead actress in “Return,” in “Eyes of Fire,” on the big screen, which I thought was incredible. That film’s director, Avery Crounse, is mentioned in the credits for “Return,” as is his company, Elysian. What was his role in “Return”? Did he help finance it?

Andrew Silver: No. Avery had an office at the same time, in L.A. Philip Spinelli, who was the line producer of Avery’s film, also produced mine. Very spiritual guy, very vague. Avery and I thought very highly of each other.

SW: Is that how you found Karlene?

AS: Yes.

SW: How’d you find Frederic Forrest?

AS: Like all independent filmmakers, we wanted to have some name value to get any play in the VHS market. So the first [part we tried to cast was] the hypnotist role. We went to Shirley MacClaine, because she believes in this stuff. And she said, “I like it, but it’s not for me at this time.” That would have put it on a different level.

Anyway, I always thought Frederic was a fantastic actor, and I thought his career would have taken off if “One From the Heart” [succeeded], because he was the star. Coppola loved him. He was great. I wish we had more time and space. Looking back, maybe we would have developed the Frederic Forrest character’s relationship with his wife even more. I’d have made the part about the parents more significant, rather than the kids. That was a huge mistake. But you don’t know this until after.

SW: What inspired the whole story idea of “Return”?

AS: There was a great book called “Some Other Place. The Right Place,” and it was very location-grounded and it was very, very long. I met the author and his wife, who was devoted to him because he couldn’t hear. He’s kind of the Faulkner of Arkansas. The author said we made a poem of his book, at the end. I liked the theme of forgiveness, of letting go. The movie has a controversial theme, and there are times in our culture when we like to punish as opposed to forgive. I loved the location, I liked these characters, I liked that they could imagine themselves in other places and lifetimes.

SW: Were you into hypnosis?

AS: I was always curious about it, and I did a documentary called “Prophetic Voices,” which profiles people that had near-death experiences. It was distributed by The American Journal of Nursing and won awards. It was a real simple doc. The journal used it in hospitals, because people would report in hospitals that they’d had these experiences. Usually the doctors dismissed this, but the nurses knew that, whether it was true or not, it didn’t matter, because these were positive experiences for the patients, and they should be honored. So we tried to support the positive actions and feelings of the nurses, and to recognize how important it was for the patients that everyone not think they were crazy. From that, I got interested in these supernormal [experiences].

At the same time, I thought, what was the dominant independent film at that time? It was a film of the paranormal based on fear. It’s called a horror film. So I thought, what if we have a paranormal film based on love? It’s a paranormal romance.

SW: Did part of you believe that you can contact the dead?

AS: I don’t know. I don’t think you can measure it in science. But I think love itself is a paranormal mystery.

SW: I detected elements of the macabre in the movie, because there’s a sexual tension between the woman and this guy claiming to be her grandfather.

AS: But the sexual thing is not physical.

SW: Until the waterfall scene.

AS: Well, they take a shower together. It’s ambiguous. Maybe they decided to go one way, maybe they didn’t go all the way. They’re attracted, but they think it’s an obstacle.

SW: How did you go about getting the film financed?

AS: It was very low budget. Family and friends financed it. It played on ABC, and before that, it had a limited theatrical run. Then it had a very good ancillary market run. We sold 15 or 20 thousand copies to the Navy. I asked the distributor if I could talk to whoever was in charge of dealing with the military. It turned out to be a woman in charge of buying entertainment. It turns out the Navy has so many submarines, boats, little boats—if you buy even one unit per vessel, that’s a lot of VHS tapes. She said, “These men, they see all these violent things, and your movie is very positive, and I thought we should have some different kinds of movies on these submarines, and give them positive energy.”

Anyway, we went to Los Angeles for casting. We thought we’d maybe shoot the movie in Massachusetts, Pennsylvania and Arkansas. But then we started meeting everybody and realized that once you’re there you can find locations for everything. You can get more deals there, there’s more infrastructure.

SW: How’d you find that fall foliage in California?

AS: The art director was great. That was shot about an hour north of L.A. We did one week of shooting in Massachusetts for the lake scenes.

SW: How long was the shoot?

AS: Four weeks. Everybody loved it, everyone wanted to work together again. John Walcutt is still working in Hollywood. Karleme said, “I like working with Avery, I like working with you,” and she did some episodic television. She was living in San Francisco and she’d come down and everybody liked her. But she didn’t like the culture. She went back to teaching and stayed in San Francisco. She said, “I’m gonna have a nourishing life, because the mood and life of this industry is not something I want to embrace.”

SW: You have characters traveling very far distances in a short period of time. I’m guessing that led to the time lapse scene on the highway.

AS: At that time, the look of that scene was innovative. They’re driving from Massachusetts to Arkansas, it’s a day and a night and a day. I was in the car, I was driving with the Hungarian cinematographer [János Zsombolyai], who was like a brother [to me], he just died a year and a half ago [NOTE: “Return” was his last movie.] We had the camera in the passenger seat. We went through the George Washington Bridge down to Washington and we kind of quit in Washington. We kept going over these bridges, which are symbolic of going to the other side.

SW: It’s a really good shot. It got lots of praise even in some of the harsher critical reviews.

[SPOILER ALERT! RESUME READING AT “Were you stung by the reviews?” to avoid spoilers.]

AS: I think what they didn’t like about the film is the idea that you would forgive such a heinous crime. It was that moment in time where people were—

SW: Well, the mother killed him, so in a way, she didn’t forgive him, at least while he was alive. Of course she can forgive him over time, and of course she has to be forgiven for killing him.

AS: And the grandfather, he nurtured a daughter/granddaughter, he took care of her mother, even though it was [incestuous]. The point is to take a positive view towards these things that are horrible. There’s no point in amplifying it. It never goes anywhere if you amplify the conflict.

SW: In the television version, the incest part is entirely excised. Why?

AS: Part of that was length, but what I wanted to get rid of was the part that didn’t fit plot-wise. All the plot was still there. You don’t really need the incest part.

SW: But you understand more why the mother would be so angry. I guess without that, she’d be mad the grandfather abducted the daughter—

AS: That’s enough.

SW: Was that a tough choice?

AS: If it’s voluntary, but if someone says you gotta cut out minutes, that’s what you gotta do.

SW: Were you stung by the theatrical reviews?

AS: Oh, it was crushing.

SW: I’ve never seen a reviewer quite like Vincent Canby. His negative reviews are so short—

AS: –and so dismissive!

SW: And I kind of wanted to do a whole series of interviews with people that I think got unfairly—

AS: You know Vincent was an alcoholic, right? Everyone knows that. So if he comes into it hungover, and then he goes to sleep through half of it, and then he writes a review…we were praying for one of the B [critics], like Janet Maslin, at the time. We just didn’t want Vincent because we know he likes big films and that he feels he’s being insulted to even have to write about a small one. So to have him review any small film—he takes that [negative] energy that he then projects out. He was so powerful in those days. It crushed me. I think it crushed everyone he gave a negative review to. At the time, that was the stamp of approval. It wasn’t film festivals.

SW: But it got a good turnout in New York nonetheless, right?

AS: Yes, because it was at the Film Forum, which has its own positive image. And it played in Boston and the Midwest. The happiest reception was in Boston.

SW: Was your plan to keep making feature after feature?

AS: I prefer chapters. Features take so much time. The idea of making an album seems more growth-oriented, more organic.

SW: I’ve interviewed so many directors that hate cutting any of their work.

AS: I think the whole idea of short stories, magazine stories, is you have the opportunity to be poetic.

SW: Do you prefer the shorter TV version of “Return”?

AS: I absolutely do.

SW: Your two early short films were a little darker, in comparison. In “Next Door,” the kid finds out his neighbors are cheating—

AS: But he grows up and puts a positive spin on it. “The Murderer” was more dark.

SW: How did you find James Woods, for “Next Door”?

AS: Well, I knew him because I was an intern on a movie called “Night Moves.” Gene Hackman was in that, too. James and I became friends. He had gone to MIT, didn’t graduate, and I went there. That movie played on Masterpiece Theater, so did “The Murderer.” “Next Door” got a great review from John J. O’Connor in the New York Times. And in those days, if you got a great review, you got 6% [of the profits] or something. Everything was contingent on reviews, there was no advertising.

As for “The Murderer,” I think it [now seems like] a pre-Internet movie, because it shows people on the phone all the time. We lit it like German expressionist [theater].

SW: Are there films of yours available in between those and “Return”?

AS: No, they’re on formats like VHS that are no longer supported. We did a children’s series, a lot of stuff on photography, we did a series for PBS about famous photographers, like Harry Callahan. I was always doing many things. I did consulting. I’m trained as an organizational psychologist, that was my degree. I did that, and some teaching.

SW: How’d you learn moviemaking in general?

AS: From “Night Moves.” Arthur [Penn] has one system: seven set-ups for scenes, and he could create a new rhythm from that.

SW: Did you shoot that way?

AS: No, I did the opposite. I think it’s a great way if you’re a Hollywood player, but if you’re a low budget player and you trust the performances and you don’t want it too cut-up…I like it to be more like theater.

SW: Jumping ahead, how did you get the idea to make a sports documentary? [“Profiles in Aspiration,” 2005]

AS: I have two sons, they were 10 and 13 at the time. And I’m a teacher and a researcher, and I noticed that [kids in that age group] were very aspirational about some things, very ambivalent about some things, and very apathetic about some things. So I was thinking, how do you move people from apathetic to ambivalent or from ambivalent to aspirational? How do you give people the tools of inspiration? You do it with sports. So I decided to make documentaries about sports.

I went out and found that the women [we interviewed] were more articulate. And I wanted to do offbeat sports, independent sports. All the rest of them were already being done by ESPN. I decided on women in special sports, where you have to be intrinsically motivated. No one’s gonna go to the pole vault or Irish dancing [if they’re not motivated]. I did 20 [short] films in eight countries. They’re all well-spoken young women.

It was always meant to be 40-something minutes long, and the market was high school libraries and sport teams. On a rainy day, the coach could put on the film.

Then I was invited to UNESCO’s [Youth Forum], in Paris, this past October. Everyone was there and they saw this film and loved it. They said, “Why don’t you come and present your film?” And [we’re planning] to show the film worldwide. We’ll figure out a way to get this out to 150 countries.

Radio Cape Cod is an aspirational film, too, about love and work. It poses the conflicts of love vs. work in a five-day period in Cape Cod, at Wood’s Hole, where people have to go to a conference. And at the same time, they fall in love. This presents time management problems. The answer is, philosophically, work your love and love your work. That was the message of that film, and at the same time it was celebrating nature.

“Second Wind” was about an 87 year-old, and that’s also asking, how do you be aspirational in that stage of your life, how do you adapt? That’s a five-chapter story, showing her relationships with the members of her family. The other methodology of this series is, maybe instead of concentrating on amplifying conflict, we have conflict resolution.

We’re doing a future chapter in virtual reality, which will reunite some of these characters.

SW: How did you get the idea to cut down the 70-minute “Radio Cape Cod” and fold it in to “May it Happen to You”?

AS: When I started doing the new chapters, I wanted to put them together with “Radio Cape Cod,” but it would have been too long. I got rid of the C and D stories, plus some of the musical montages. That brought it down to 43 minutes, and putting that together with “Second Wind” and “Surprise Engagement”—rather than thinking of it as a feature film in minutes, you can think of it as an album.

SW: How’d you get the idea to shoot in Cape Cod?

AS: Since the theme was environmental and the other theme was science, that part of Cape Cod, where the oceanographic institute is—it made sense, because they’re MIT people. And then it made sense to make [Tazmin Outhwaite’s character] English, because we always think of English interviewers as more experienced.

SW: Tell me about the virtual reality project.

AS: It was shot but we have to redo the sound, and re-record the dialogue. The problem with VR–the constraints are, you can’t be in the frame. The sound guy is around the corner, the radio frequency can’t go past the wall, so the volume dropped and we couldn’t get the right dialogue quality. You have to reexamine all of the working methodologies you’re used to. You have to be really far away from the actors. It’s not ideal. Next time I’m gonna do the flat versions first and then do it again in VR, so you have two different things you can cut between. In VR, you’re missing the frames and the cutting, and you’re missing certain rhythms.

SW: How’d you learn about that type of photography?

AS: In 1995, a colleague and I were experimenting with VR at the Coolidge [Corner Theater, in Brookline, Massachusetts], which I was one of the co-founders of. It didn’t work in those days, there was no internet and no cell phones, so the idea was you’d do VR in a theater, so everyone is sitting there in a 100-seat theater wearing this mask, and that was kind of dumb. And people didn’t like not being in reality. Their purses could be pickpocketed, people could be looking at them without them wanting to, etc. So we kind of gave that up.

Now we’re coming together again. He’s head of VR at Harvard. He’s been in it full-time since then, he’s an expert, and I’ve been in and out of it.

SW: Do you think you’ll ever do another feature-length film?

AS: I’d be happy to do just small ones.