“They Ought to Be on DVD” is a recurring Hidden Films series dedicated to movies that received a New York City theatrical run—and thus a New York Times review—but no subsequent release in ancillary markets. Through interviews with cast and crew, we attempt to answer why.

“I’m the first filmmaker to make a movie about a heterosexual getting AIDS, and about date rape. I’m very proud of that. I did a good thing.”

—Producer/writer Fred Carpenter

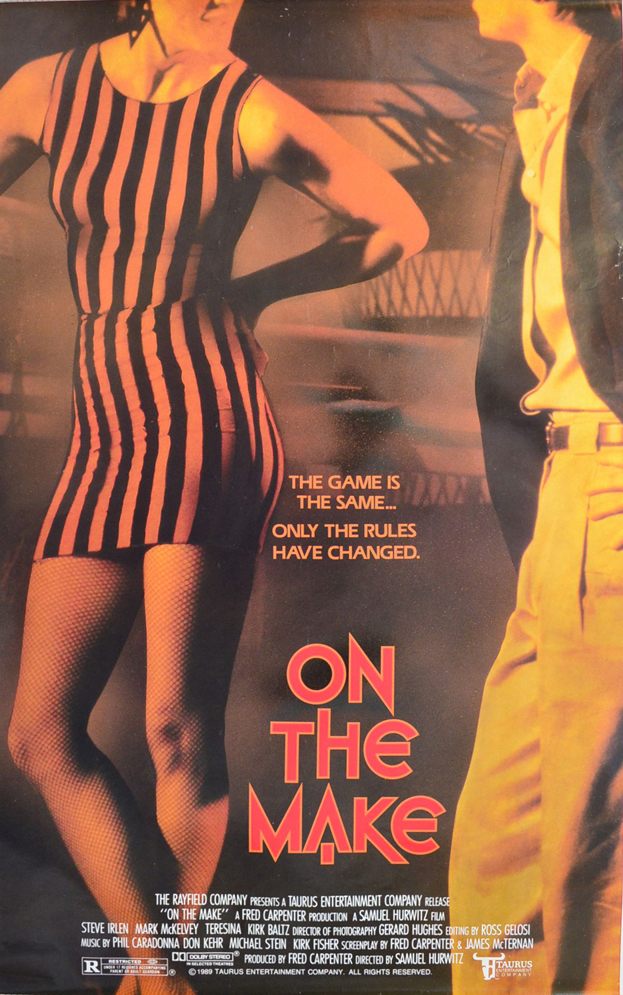

In April 1989, “On the Make,” a minuscule-budget cautionary tale about promiscuous clubgoers, opened at the legendary, now-defunct Boyd/Sameric movie palace in Philadelphia. It was the start of a five-month run at United Artists-operated theaters in various cities, including New Orleans, Tulsa and Miami, culminating in a brief New York City release. According to an April 1989 New York Daily News article, the distributors, Taurus Entertainment, wanted to test how the movie performed among the college crowds in smaller markets before unleashing it on The Big Apple.

Taurus’ caution was understandable, for reasons beyond the film’s meager production values. (Accounts of the film’s budget have varied; a 1989 Newsday feature on “On the Make” pegged it at $120,000; a 1991 Newsday article said it was $280,000; and several insiders interviewed for this story cited figures within that range). There were no stars in the picture (although Kirk Baltz, playing a loathsome, predatory disco denizen, would later mesmerize audiences as the tortured police officer in “Reservoir Dogs”). It had, more or less, only one setting, having been shot almost exclusively at the East Meadow, Long Island nightclub Zachary’s, for roughly two weeks in February 1988. And it wasn’t even part of an easily marketable genre, such as action-adventure or teen comedy. In fact, despite several amusing sequences, the film was overall downbeat.

Furthermore, all of “On the Make’s” chief creators were very green. It was the first full-length outing for screenwriter/producer Fred Carpenter, a Long Island lifer and Stony Brook University film school graduate; 24-year-old director Sam Hurwitz, son of the late filmmaker Harry Hurwitz, who helmed the 1971 classic “The Projectionist”; associate producer (and Hurwitz’s close friend) John Melfi, later of “Sex and the City” and “House of Cards” fame; and co-writer James McTernan, a former Naval aviator and P-3 fighter jet pilot, and a longtime pal of Carpenter’s.

His dad’s cinematic influence aside, Hurwitz, a School of Visual Arts graduate, had the most filmmaking experience, having already directed and/or produced several short projects with Rob and Chad Lowe, Robert Downey Jr., Charlie Sheen, Martha Plimpton and Johnny Depp, just before they hit the big time. (Hurwitz had befriended most of them during junior high and high school, in Santa Monica and Malibu). These shorts, however, had never been released—and still haven’t, mostly due to music licensing issues—so Hurwitz, despite his enviable group of friends and considerable skills, was hardly a name talent at the time.

Nonetheless, Taurus’ late chairman Stanley Dudelson—a fellow Long Islander who appreciated “On the Make’s” timely message—decided to take a chance on the film. Not knowing what to expect, Carpenter, Hurwitz, Melfi and McTernan journeyed to Philadelphia on opening day.

“The place was packed,” Carpenter remembered. “We’re on line, and Melfi’s looking at Sam, like, ‘I can’t believe this film fucking sold out.’ We get into the theater, the trailers come up…and then ‘Rain Man’ starts playing. It was the wrong fucking theater! The theater next to it was playing ‘On the Make.’ We go in, and God’s honest truth, a guy in the back was getting a blowjob, and a guy in the front was vomiting. It killed me. I went from the ecstasy of ‘I think I’m gonna buy a BMW,’ to ‘This movie just bombed,’ you know?”

(NOTE: In a September 1989 Newsday profile on Carpenter, just before “On the Make’s” New York premiere, Carpenter told a far less sordid—and less bleak—version of the same story, saying that the “On the Make” Philly audience, while still paling in comparison to that of its Academy Award-winning neighbor, nonetheless totaled around 100.)

“Maybe I said that so it wouldn’t look that bad,” Carpenter chuckled.

The film’s slump continued in Philly and similar-sized cities, but performed marginally better during its New York run in September 1989, receiving decent reviews in Playboy, The New York Times and The Village Voice. Ultimately, however, “On the Make” only pulled in—according to Carpenter—around $55,000 total at the box office.

Taurus—which eventually became Blairwood Entertainment, now run by Dudelson’s son James—later arranged for Overseas FilmGroup to handle foreign distribution for the film, but “On the Make” was never granted a television broadcast or VHS release, in any market. Overseas FilmGroup went through many new owners over the next three decades; the latest one, Alchemy, filed for bankruptcy last summer. It remains unclear which company even holds the film’s original negative. James Dudelson, reached for comment, said he could not confirm if the “On the Make” negative is still in the Blairwood library; nor could a trustee for Alchemy. And when I first reached out to Carpenter and Hurwitz early this year, neither had a viewable copy of their own film.

Incidentally, in 2014, a curator/archivist from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Ed Carter, reached out to Hurwitz, saying he retrieved a duplicate negative of “On the Make” from the recently shuttered film processing outfit DuArt. (Carter, reached by email, said that according to paperwork included with the negative, revisions were made to the print between October 1988 and March 1989, by DuArt as well as negative cutter company J.G. Films). Carpenter recently told Carter to restore the negative at the Academy, rather than return it to him.

“I just want to make it so that when I drop dead, people can watch my films,” said Carpenter. “If someone doesn’t see a movie, it doesn’t exist.”

Asked why “On the Make” was never distributed on VHS, Carpenter’s theory is that “United Artists were basically picking up a couple of movies to play in their theaters to lose money, so they’d get tax breaks. They took a couple of [newspaper] ads out for ‘On the Make,’ but there was no push.”

Despite this and other soul-crushing setbacks over the last 28 years, Carpenter, a garrulous, kindhearted dynamo who still lives with and tends to his mother in Shirley, Long Island, never lost his zeal for the craft. (A longer Q&A with Carpenter will follow soon on Hidden Films).

In conversation, Carpenter zooms rapidly from charming self-aggrandizing (“I’m a fucking warrior, man”) to heartwarming self-abasement (“Life has passed me by, my friend. I never had kids. Every Christmas gets lonelier. Doing what I do, I gotta be out of my fucking mind.”) Looking back, there are several things he’d change about “On the Make,” were he to make it today. (In fact, two years ago, Carpenter wrote and directed a 1970s-set film very similar to—but less memorable than—”On the Make,” entitled “Disco!” and available for viewing on Vimeo). But he remains especially pleased with the original film’s primary distinction.

“I’m the first filmmaker to make a movie about a heterosexual getting AIDS, and about date rape,” said Carpenter. “I’m very proud of that. I did a good thing.”

That the film got granted any sort of mainstream release was not only a point of pride for Carpenter, as I learned via phone interviews with various cast and crew members, conducted between May and September 2017. Regardless of its ultimate fate, it is still remembered as a happily naive, seat-of-the-pants experience by most of its participants, many of whom remain—or had a long career—in the industry. The shoot resembled a college reunion, as several bit players and crew people were buddies of the filmmakers. And few of them have lost touch for personal or upsetting reasons; it was just a consequence of careers moving in different directions.

Carpenter continues to make movies in his beloved Long Island, or occasionally Queens— even if his film is set as far away as Alabama. He has a knack for shooting fast and cheap, even when his cast includes such notable talent as Sean Young, Armand Assante and Eric Roberts. After “On the Make,” he variously wrote, produced, directed and even starred in 13 feature films (with a 14th, “Dinosaur,” wrapping up soon). While no other movie of his has been granted a theatrical run, a great many made a profit via cable, VHS, DVD or VOD distribution. His most successful film to date is the 1996 crime flick “Murdered Innocence,” written by and starring Carpenter, directed by Adam Sandler crony Frank Coraci, and eventually sold to Columbia/TriStar.

Hurwitz now runs a thriving film marketing business and has directed hundreds of behind-the-scenes specials on major Hollywood movies. He also recently released his first feature directing project (since “On the Make”) on VOD, the intoxicating documentary “8 Broken Hearts,” in which adults plagued by traumatic childhoods open up on camera. (Hurwitz, who had never before been interviewed, said that he himself was a victim of abandonment, as his mother walked out on the family at an early age). He has a forthcoming children’s cartoon web site called Video Poodle, several published books about coping with baldness, and another book—“Hooray for Doody!”—that takes a humanitarian look at the flushing of excrement.

Mike Royce, then a close buddy of Hurwitz and Melfi’s who served as gaffer for “On the Make,” spent most of the 1990s on the stand-up circuit, where he met Ray Romano and eventually became a writer/producer for “Everybody Loves Raymond.” He currently produces and writes for the Netflix series “One Day at a Time.”

Makeup and hair artist Angela Nogaro, who said she was brought into the movie by Hurwitz’s stepmother Joy, is still working on big film and TV productions. Her one-time roommate, actress Grace Naughton, also had a hand in “Sex and the City,” and now runs her own production company, Grit Films.

Longtime Broadway actor/singer and musician Donnie Kehr, a one-time roommate of Hurwitz’s who composed the score for and appeared in “On the Make,” has performed in recent Broadway smashes such as “Jersey Boys.” Yul Vazquez, then a bandmate of Kehr’s in the EMI-signed rock outfit Urgent (“I still had my mullet from that band, in the movie,” Kehr remembered), has led a prolific acting career, as has Robert DiTillio. And actress Laura Grady became a big-time body double, most notably for Helena Bonham Carter in “Fight Club.”

(NOTE: Several of the cast and crew members are, for reasons unexplained, not credited on the film’s imdb.com page, but are listed at Hollywood.com, which erroneously cites second unit director Alan Jacobson as a co-director.)

Despite the now-lucrative careers of its makers, I’d have never heard of “On the Make” if I hadn’t stumbled upon its mixed but gentle review by Caryn James of The New York Times. I also read some vicious pans from earlier in the film’s run, which only heightened my interest. Maybe it was an unintentionally funny classic waiting to be rediscovered.

It is not, as I would find out when one of its central actresses, Teresina Sullo (credited solely as Teresina in the film), kindly sent me a never-distributed VHS tape. (Though most public data on the film reveals its running time to be 77 minutes, the version I watched runs a fleet 69 minutes; no one I interviewed knew why).

To be sure, the film has its share of flaws, and it’s a shame that the most glaring one involves the AIDS shocker. This bombshell is dropped literally 80 seconds before the ending, via clunky voice-over and clunkier flashbacks/flash-forwards; it also interrupts the most naturalistic, well-acted scene in the entire film (in which a player angrily goads one of his lovers to get an abortion). The camerawork is often jerky, the dance editing choppy. Much of the dialogue is stiff, obvious and heavy-handed. (“You’ve had sex every day of your life, but you’ve never made love”; “I’ve never been in love; did I miss out?”) And the movie is larded with filler shots—of beer being poured, disco balls spinning, extras French-kissing—that were obviously meant to pad out the running time. (Both Carpenter and Hurwitz remembered that they came up short after editing, and were forced to shoot some mundane external scenes—mostly of the two lead characters hobnobbing over lunch and touch football—in the spring of 1988).

So it’s remarkable that, with all that going against it, and nearly 30 years later, “On the Make” has an undeniable staying power. It could very well be that the inexperience of the filmmakers is what gives it a certain blunt, off-kilter, gung-ho spirit, which would elude slicker visionaries. The main element that its harshest critics attacked—the numbness and claustrophobia of the club setting—registered as authentic and haunting to me. Unlike, say, “Wedding Crashers,” a film that portrays casual sex and bachelorhood as endlessly fun and self-validating for two hours, and then suddenly shifts into preachy gear, “On the Make” views caddish behavior in a miserable light from the outset.

The stud character, Kurt (played by Rob Lowe lookalike Mark McKelvey), brags that he’s nearing his 100th conquest, but most of what’s shown on-screen are the humiliations and rejections he has to endure before he hits pay dirt. There is zero eroticism, even in the film’s lone sex scene; the girl in question looks vacant and bored, and Kurt sums up the encounter with a smug self-analysis: “I was great.” And killjoy topics such as unwanted pregnancies and STDs are brought up frequently.

In the most bizarre sequence, Kurt’s lovesick pal, Bobby, played by Steve Irlen, learns that the comely woman he just made out with has herpes; he orders a dozen or so whiskey shots, gargles them and spits them out on the floor; Kurt, realizing he previously slept with this woman, joins Bobby in the garglefest; and the afflicted girl and her friends laugh disdainfully at these fools. The scene then abruptly fades out. It’s eerie, sad and funny all at once. (So is the fact that the actress who plays the woman, Holbrook Adams—who is also glimpsed on the movie’s poster, shown above—never appeared in another film, though a few of her wedding announcements were printed in The New York Times.)

There are other pluses. While it succumbs to cringe-inducing clichés elsewhere, “On the Make” wisely eschews that tired “Only the good die young” maxim. Here, the mean lothario, not the sweet-natured hero, is the tragic figure; asking audiences to abruptly feel compassion for such a bald-faced jerk is bold, indeed.

The catchy techno songs, mostly written by Hurwitz’s pal Michael Stein, rank remarkably low on the Cheese-o-Meter.

And as played by Kirk Baltz, Richard, Bobby’s thuggish, coked-up tormentor, is so creepily obsessed with the rather bland Bobby that a whole separate film could be made about him. He’s a bully towards Bobby and virtually no one else, hellbent on seeing him unhappy. Bobby is still pining over an ex, who had dated and dumped the abusive Richard many years earlier; inexplicably, Richard still carries a grudge. He taunts and cockblocks Bobby while the latter attempts to romance a new woman (Jennifer Dempster, who was later on ESPN’s “BodyShaping”; she was unavailable for an interview). He’s furious that Bobby won’t challenge him to a fight, and when he later pummels Bobby, the victory is too easy. The only way, ostensibly, to get a satisfying rise out of Bobby is to rape Bobby’s virginal younger sister (Teresina), which Richard attempts, practically under Bobby’s nose, in the club’s stairwell. This is no standard foil; Richard’s behavior is blatantly sadomasochistic, even homoerotic.

Most audiences and critics sadly missed or turned a blind eye to these quirks. They may have been too incensed by the cheap, hasty look of the film, or its vacillation between melodrama and dopey comedy, to notice. But without that shift in tone, the film would be a run-of-the-mill, love-conquers-lust fable. Despite the overall dreary aura, “On the Make” is dotted with lightning-fast, often hilarious episodes of ill-fated seduction attempts throughout the club. (Most of these comic set pieces were either suggested by Hurwitz after he read the script, or thrown in on the fly during shooting).

Donnie Kehr (billed here as Don Alexander, which Kehr explained was “a union issue—I had to, and I can’t say why”) appears in the funniest scene, as a club patron who schools Bobby on the only place he is guaranteed to meet girls—outside the ladies’ room.

“That was my childhood,” said Hurwitz. “As a teenager, I said, ‘Wait, stand on a sweaty dance floor and jump up and down to music? Or go to where every single woman is gonna eventually end up, by the end of the night?’ So I turned that into a joke.”

Almost as funny is the character played by Grace Naughton, the only woman in the nightclub to fall for the worst pickup lines. When Kehr—on temporary leave from the restroom—presents her with his patented “Wanna fuck?” introduction, her eyes light up, and she chirps back, “Really? You wanna fuck me? Reeeeee-leeee?!” Turned off, Kehr hits on Yul Vazquez’s character, whom he thinks is a woman; the results, of course, are disastrous.

Various crew members were asked by Hurwitz to cameo as horny and/or incompetent males and their disgusted, sharp-witted female respondents. Mike Royce, for instance, is billed as Condom Guy, and Angela Nogaro as Condom Girl. Total strangers on a packed dance floor, they meet when he says, “I’m wearing a condom.” Her harsh rejoinder: “Were you born a dick or do you just practice?” (Nogaro said she came up with this one-liner during a bull session with the crew, who encouraged her to use it in the film). Melfi also appears, with a less abrasive but equally groan-worthy line, after being denied a telephone number: “Can I have your area code, then?”

We don’t even see whom DiTillio’s character is hitting on, only his sunglasses-wearing face in extreme close-up. “I’ve been watching you for an hour,” he leers at the invisible woman, and then, while taking the glasses off, adds: “You look like my mom.”

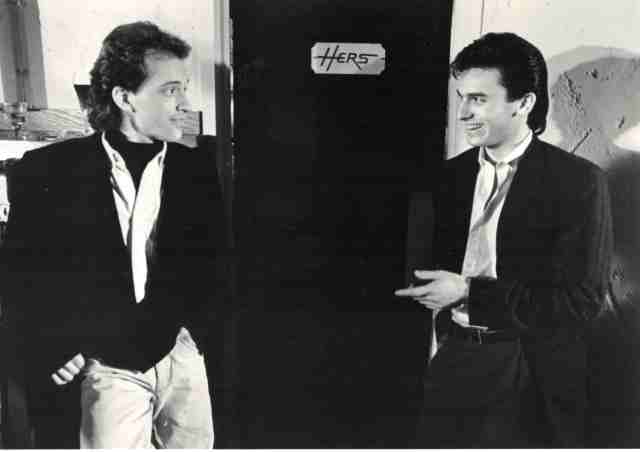

DiTillio, via email, said he provided his own wardrobe for the film, “which I thought was stylish for the 1980s!” He used a photo from that scene, pasted below, as a headshot for an audition years later.

Hurwitz himself appears as a cheating husband caught red-handed by his wife; when I talked to him, he had completely forgotten about the sequence.

“It was badly looped,” he said, after re-watching the movie. “I got slapped in the face [in the scene]. I’m not an actor, I don’t covet acting, so I wouldn’t have been like, ‘Oh my god, this is my moment!’”

******************

Few of the film’s comic interludes were in Carpenter’s original script. Neither was the AIDS theme. He initially envisioned “On the Make” as an updated, more moralistic “Saturday Night Fever,” one of his personal favorites. (Kehr, by sheer coincidence, said he was an unbilled 13-year-old extra in that 1977 classic, given one line—”Hey, mister,” delivered to an indifferent John Travolta—that was ultimately cut).

It was Carpenter’s pal James McTernan who suggested the AIDS twist, “because [the character] is so promiscuous,” said Carpenter. “It hit home for a lot of people, because this was ’88, and back then people didn’t think heterosexuals died from AIDS.”

“It wasn’t just a gay disease,” said Melfi. “As a gay man, that was important to me, to tell that side of the story.”

McTernan, who today flies for American Airlines and resides in Florida, noted that AIDS “was originally called GRID—Gay-related Immune Deficiency. Eventually a heterosexual acquired it and the gay activists wanted it changed to AIDS. It was a fairly new disease. I personally had a fear, like, ‘If you can get it from hypodermic needles, why wouldn’t you be able to get it from a mosquito?’ There was a lot of uncertainty about it. We started thinking we could do something, to at least let people pause and think about what’s going on.” (McTernan’s only other produced screenplay was for the 1992 thriller “Small Kill,” again co-written with Carpenter, and starring/co-directed by Gary Burghoff of “M*A*S*H.” But he said he still has the screenwriting bug.)

Teresina Sullo said that, at the time, “AIDS was not in my consciousness. It wasn’t discussed in college, AIDS and a man’s responsibility for it. The film was brave in what it had to say.” (Sullo appeared in “Small Kill,” as well as a few more theatrical and television productions, before becoming a fitness and relaxation trainer in Los Angeles).

Carpenter had already worked with Hurwitz, on the short 1987 film “Chase of Temptation” (available for free streaming, along with many of Carpenter’s films, on the website iDriveinMovie.com). Carpenter wrote the script for “Chase” a year earlier, shortly after leaving a long stint in the publicity department for Paramount Pictures. (“I should have stayed there and made my movies on weekends,” Carpenter groaned. “Why I left, I’ll never know.”)

“I was putting together a soundtrack for ‘Chase,’ and I told this [producer], who was dealing with Ronny Wood, that I needed a director for a short film. And he told me he had somebody.” (Hurwitz said that, to his knowledge, it was his contact at a production assistant job on a Joe Cocker video that linked him to Carpenter).

“When I saw Sam’s short films with Robert Downey, Jr. and Charlie Sheen, I thought, ‘This guy’s a player. If these guys are working with him on shorts, someday he may be working [with them] on features,'” Carpenter said. “That really sold me.”

“To this day, there’s a difference between the work you do for passion and play, versus [where] someone’s paying you,” said Hurwitz, who began making his own movies at age 10, with his father’s 16mm Bolex camera. “Those [short films] were from the days that no one paid me for anything. No one gave me notes. I had the time and space to just screw up.”

(NOTE: Despite the aforementioned music rights issues in Hurwitz’s short films, Charlie Sheen, during one of his ill-fated 2011 solo tour showcases, screened clips of a 1986 movie he and Hurwitz worked on called “RPG, ” starring Johnny Depp and Dolph Lundgren. A shoddy clip of that event, taped by a heckling audience member, can be viewed on YouTube. Hurwitz said that the only other short film from that time period that got any sort of distribution was “A Life in the Day” (1986), starring Sheen. “I had a distributor and she’d find these obscure little things. Like I’d get residuals from a TV show in Japan, or a TV program on a cruise ship,” said Hurwitz.)

“I took Sam to a diner,” continued Carpenter. “I love going out to eat! We got to know each other. Sam’s not an alcoholic. He doesn’t have bad habits. He works hard. He’s a very high-end, classy person. Why wouldn’t I have him direct my movie?”

And so work began on “Chase,” which was filmed mostly on Wall Street, with a few opening shots of then-seedy Times Square and its many vagrants thrown in.

“Fred had his own aspirations to be a filmmaker, but I don’t think he was ready yet to take it on himself,” said Hurwitz. “And so he gave me a lot of freedom to be experimental and creative, with little money. I remember it being a big deal, because I had not been hired to direct before. I was super grateful about that.”

“Back then, Wall Street on Sunday was a ghost town,” he continued. “I think that’s why so many people filmed there on weekends. We could not afford a permit, so I dug up an old one and we whited out the date and the title, and put a phony title in. Sure enough, a cop pulled up and said, ‘Let me see your permit.’ I’m like, ‘Shit, we’re going to jail!’ And then he said, ‘Bye, good luck.’ We did everything kind of dangerously. We had a lot of cool in-camera effects, and there was some groovy sound design on it. We played with camera mounts on [top of] cars. I had a good time, it was fun.”

One such “in-camera effect” (repeated in a later Carpenter short) was a jarring zoom-in shot through a priest’s vestment, followed by a schizoid fantasy sequence involving a car wreck, a strip joint and a hellish subway.

“There’s a lot of stuff I [borrowed] from ‘The Exorcist,'” Carpenter admitted. “I love long lenses, big lenses. I think William Friedkin is one of the top ten directors of all time, a brilliant fucking genius.”

With his first film under his belt, and his full-length screenplay now given a polish by McTernan, Carpenter launched a zealous fundraising campaign for “On the Make.” His methods were unorthodox, to say the least: he called strangers out of the phone book.

“I called dentists,” Carpenter elaborated. “These guys have money. And they love showboating. The biggest egos are these plastic surgeons. I went to a guy who specializes in breast implants and he wanted to get into the movie business.”

“To get rich people to separate from their money—that’s the hardest thing to do in the world!” Hurwitz exclaimed. “The fact that Fred can do that is an amazing talent!”

“Listen, they go to the bathroom just like me,” said Carpenter. “All they can do is say no. It’s angel money. They’re not giving me $200,000. Maybe they’re giving me $5,000 or $10,000.” (Carpenter said the biggest individual handout he received from a doctor was $25,000).

With the money and locations secured, it was a no-brainer for Carpenter to ask Hurwitz to return to the helm as director.

“I went into it [saying], “How do I make it look as expensive as possible, and get the best talent we can afford, with the limitations we have?’ Which I believe we did,” said Hurwitz.

“The thing I felt was really missing from the script was some humor, some [sense of] fun that kids have if they’re going out,” he added. “That’s what I pressed with Fred. So I came up with some gags. I don’t know how they play now, with audiences today. It’s a film based on its time period.”

“I would say he made [the shooting script] better,” Carpenter acknowledged.

Nogaro remembered that the original script was “just not well-written. It wasn’t solid. It was really elementary. That was a lot of the fleshing-out part that Sam Hurwitz had to do. He definitely tried to get more off the page than what was there. The whole crew did. There’s a mentality about a crew, where it doesn’t let itself fail.”

Other than adding more levity to the script, however, Hurwitz showed nothing but loyalty to Carpenter for the gig. He also remembered feeling way in over his head, but enjoying the ride nonetheless.

“No one’s ready to make a feature, if you’ve never made a feature,” said Hurwitz. “Especially one that’s small, where you really have to pick up a lot of the slack yourself. You have to keep it up for many weeks, versus a short film where you do it in a day or couple of days. And a lot of folks were brand new at this. We purposefully cast non-SAG talent, which was difficult.”

But theater actor Kirk Baltz, despite his inexperience on-screen, blew everyone away. Everyone interviewed for this story predicted, at the time, that Baltz was the likeliest candidate for fame. (And they were correct: he still performs frequently, also teaching acting seminars all over the world.)

“Kirk saw right through me that I had no idea what I was doing,” Hurwitz chuckled. “I thought, ‘He’s so much better than me, he’s gonna discover what a phony I am.’ He made me very nervous, because he had a kind of edge about him in person.”

“I was brand new with him right there, so it was probably more of an identification than seeing through him,” Baltz responded, laughing humbly.

“I thought, ‘The world must be really loud inside, to Kirk, so he’s just crunched up on the outside,'” Hurwitz continued. “I know those people and understand it. It didn’t seem like life was easy for him, or peaceful, at least back then. But I always believed that he had tenderness on the inside. You don’t protect yourself unless you have something to protect. I always saw a lot of heart in him. He’s really a kind man. I was in awe of his talent.”

“One of the strong points of the acting in ‘On the Make’ is Kirk Baltz,” Carpenter concurred, adding that “Sam got that performance out of Kirk. Sam was very much into therapy. I don’t know if he ever went, but he studied it, and he took that knowledge into working with the actors.”

“I remember Baltz being off on the side, on his headphones,” said McTernan. “I’m sure the other [actors] took it seriously, but he so obviously took it intensely.”

“I do remember him sitting in corners,” Melfi chimed in.

“Kirk was a very intense method actor guy,” said Nogaro. “I think he’s calmed down since then. I just bumped into him at a birthday party.”

“I tried getting Kirk for something else later and he said, ‘I just did a movie with Harvey Keitel,’ and he was doing something else,” said Carpenter. “He was polite but he wasn’t interested.”

Baltz said he has scant memories of the film.

“I remember the nightclub,” he said. “I remember doing my scenes. I remember that in the rape scene, I broke a finger, when [Irlen’s character] comes in and beats the shit out of me.”

“I remember, uh, my hair,” he added, with a pained laugh.

“The rape scene was supposed to be in a car, but it was so cold, I literally couldn’t do it,” said Sullo. “It was 20 degrees. We were all wearing mittens. ”

“Sam Hurwitz got them out of the car, found these long steps, and [filmed] him attacking her,” said Carpenter. “If I cut that scene as, like, a little mini-movie and put it on YouTube, it’d be blowing people away.”

“When we [re-shot] the scene, the cops actually showed up, and we had to prove it was just a movie,” added Sullo. “We had to shoot it again, and the sound girl and the boom girl couldn’t watch it again.”

“I remember that,” said Melfi. “We didn’t have enough location support to block off certain sessions. And we drew too much attention to ourselves. That scene was always uncomfortable. It had a general grittiness to it.”

“On the Make’s” crew was so small that several people—including Hurwitz—were obligated to perform two or even three jobs at once.

“John Melfi and I were doing art direction,” Hurwitz said. “We were painting paper to cover mirrors up in the club, with some weird design. I remember it being harder as we went along. We couldn’t afford a dolly [for one shot], so we used a shopping cart, or maybe a wheelchair. I had no sleep after awhile because there wasn’t time, and we kept falling back.”

“But at the same time, I had the opportunity to do a feature for hire,” he added. “Who the fuck gets to do that in their lifetime, much less at 24?”

In an email, Grace Naughton agreed that “everyone wore many hats. When I wasn’t acting, I was a costume assistant. A terrible one. I ended up burning to a crisp Kirk Baltz’s own costume. He was very nice about it. But I never worked in the wardrobe department again.” (Baltz said he did not remember that incident. “But tell her it’s OK if you talk to her again,” he added, chuckling.)

“I remember the costume designer [Melissa Merwin] helping with the production side,” said Melfi. “And I did assistant camera [work] for awhile.”

“Because of the budget constraints, there was a lot of changing on the fly, moving set pieces around,” said assistant director Bart Herbstman, who is now a public school teacher in New Mexico. “Compared to me, Sam and John were kids. They managed to pull together basic camera packages and lighting. On commercial sets, you can throw money at problems, but they had to creatively solve their issues. It was a marvelous experience.”

“It was very difficult,” said Melfi, who added that Herbstman, then a film consultant with years of experience in television, music video and commercials, was a great mentor to him. “But I don’t remember there being any complaints.”

In fact, the only whining that Carpenter personally witnessed on set came from one of the two stars (he couldn’t remember which one).

“It was something about not getting the right herbal tea,” he said. “This is right in front of James McTernan, who’s been serving our country, flying secret missions for the government. He was amazed when people on the set complained about bullshit. He was like, ‘Can I bitch-slap this guy?'”

“That’s something I would say,” McTernan responded. “I remember Bart telling me that normally, for low-budget films like this, they’d be eating cheese sandwiches three times a day. Fred had hot buffets for everybody. Nobody was getting wealthy making this thing, obviously, on the salaries, but he understood [the need for] that, for morale.”

“I think [we made] $100 a week,” said Melfi. “It wasn’t about the money. Sam wanted to do it and we all loved Sam.” (Melfi, along with Royce, met Hurwitz at a teleprompter job in the early 1980s, and both men worked with Hurwitz on several of his aforementioned short films, as did Kehr. Through Hurwitz, Melfi subsequently met Downey Jr. and his eventual girlfriend, future “Sex and the City” star Sarah Jessica Parker.)

“It’s a smart thing to surround your director with talented people that are his friends, as opposed to strangers,” said Carpenter. “And I remember Sam had conversations with his dad as far as who to bring in, who not to bring in.” (The senior Hurwitz would also play a key role, later on, in helping his son deliver a tighter final edit of “On the Make.”)

“We had this motley crew, a wonderful group,” continued Melfi. “I say this to young folks now, who ask, ‘What’s your approach to work?’ And I just say, ‘If you see a void [on set], fill it, and then you’ll get recognized and keep moving up.’ Back then, you had to work your ass off for no money. I think I made $350 on ‘One False Move’ [in 1992, as production coordinator], driving a broken-down Honda Civic. That’s just what you do. Do what you love and the money will follow. That group represented that [mentality]. We were living on hotel room floors, eating pizza. It was like a frat house. And we loved each other.”

“I just loved seeing Sam and John’s dreams come true,” said Herbstman. “I didn’t do it for the dough!”

“I remember Sam being very organized,” said Kehr. “He really wanted to make a good film, and I think he did OK given the tools he had. As stressful as it was, we were all just friends and happy to be making a movie. We took it seriously, but we thought, ‘We’ll show up, hopefully the performances come out OK, maybe the dialogue’s not so great, but you know, we’ll make it work.'”

“It was shot quickly and we were all amateurs, so some stuff was overacted,” he admitted.

Bit player Cynthia Koury-Papa, who eventually entered the stand-up sphere and occasionally appears in a troupe with husband and comic Tom Papa, said she remembers Carpenter in particular as “a real go-getter. I was impressed that he was even piecing this film together. The results of it are one thing, but I was impressed by him.” (Twenty-eight years later, Koury-Papa still remembers her character’s brutal putdown, to a salacious male suitor: “I spent $90 on this dress. Don’t make me puke on it!”)

“They filmed it in so little time that what Sam Hurwitz did is a miracle,” said Sullo. “He was a little neurotic, but under the circumstances, I don’t know who wouldn’t be. We had nothing to do but feel fortunate we were working on a movie. We weren’t anybody.” (Hurwitz, in turn, had nothing but praise for Sullo. “She was one of the most positive human beings I’d ever met. I didn’t know anyone trying as hard to get work. I remember wishing people saw what I saw, how special she was.”)

Melfi agreed that the extreme time limit was the most stressful component of the whole experience.

“There was some drama with some of the locations,” said Melfi. “The vendors said, ‘You gotta get out of our place.’ We could only be in places so long, so we always had to rush.”

The biggest challenge for Hurwitz was “finding diversity in the dark room of a club. I remember working tremendously hard with our DP [Gerard Hughes], going, ‘How do we make something look different, when at the end of the day, it’s the same group of people, the same dark walls and railings in the same club? How do we not make it feel flat, all with very little resources and very little gear?'”

“My advice has always been, try to write a script that takes place in one location, and inside that place is a multiplicity of locations,” Carpenter explained. “That’s what we tried to do.”

Several people said the monotony of the setting gave them cabin fever, at times.

“I remember being trapped in that fucking club,” Royce put it bluntly. “The ventilation was not great. It was hot and sweaty and weird.”

“We smoked the club [out], and it’s all day long in a small, dark space, not looking at daylight, and in the winter, which is doubly depressing,” Hurwitz added.

“The club scenes keep popping up in my brain as being endless,” said Melfi. “Having [done] at least a hundred others [since], they’re always unruly and they’re really hard to shoot. There’s so many angles to cover because there’s so much space to fill. And you always end up in different parts of the club, and someone’s always having sex in the club, on every show.”

“I also remember the extras being unreliable,” he added. “The background stuff can be trying. It’s so boring for them.”

Speaking of sex and extras, several people interviewed recalled that members of the cast and crew enjoyed frequent off-set dalliances with extras, most of them film students brought in from nearby Hofstra and Stony Brook.

“There were a lot of young hotties [around], and a couple of people enjoyed the fruits of that experience,” said Hurwitz. “I didn’t have time [to partake]. I actually wish I had more time. But I was working from the time I woke up to the time I went to sleep. And constantly getting [late-night] calls, like, ‘Sam! Come out! They’ll do a threesome with you!'”

“Yep,” he added, ruefully. “I turned down a threesome. Absolutely.”

“I had a car and nobody else did,” Nogaro laughed. “So Mark used to borrow my little Datsun all the time because he was trying to get laid, of course, by all the young actresses on set.”

“It was kind of ironic, because it was this cautionary tale, they were trying to say this is behavior you shouldn’t do, and yet I remember many members of the cast all just sleeping with each other,” said Koury-Papa. “I remember a lot of female extras in the club really hanging on the leads, and I remember hearing about closed parties. I wasn’t a part of any of that, but I just enjoyed the gossip.”

“I had such a crush on [Mark],” admitted Laura Grady, who plays the aforementioned girl that Kurt knocks up and then publicly lambasts. “I was excited to go to work. I just remember he was such a good actor, when he was yelling at me. I really was crying. I was a wreck.”

“Mark and Steve were cute, and the girls melted,” said Sullo. “They got peacock chests. They weren’t too arrogant, though. There was probably more partying going on than I knew about.”

“I did hook up with Sam’s brother,” she admitted. (Billed under the stage name Michael Ross, Hurwitz’s sibling plays a small part in the film).

“I remember looking at Mark and thinking, ‘I wish I was him, because he’s getting laid way more than me,'” said Carpenter. “People used to mix him up with Rob Lowe.”

(NOTE: Speaking of Lowe, another highlight of that shoot for Carpenter was Lowe and Anthony Michael Hall’s appearance at the film’s wrap party at Peggy Sue’s, then a Greenwich Village hot spot. During one of our phone calls, Carpenter read aloud from an August 1988 New York Daily News mention of this party; the article is currently pinned up in his garage. Hall’s presence was likely due to his friendship with actor Jeff Fahey, whose brother Phillip appears in “On the Make”; a New York Times article from November 1994 mentions that the Faheys co-owned Peggy Sue’s, and that one of their later clubs incorporated Hall as a silent partner. Carpenter also remembered that Downey Jr. attended a March 1989 preview screening of the film in New York, to lend his support, and that Rob Lowe and several cast members hung out at Singalong, a local karaoke bar where Kehr emceed. Having these stars in such close proximity, Carpenter said, “juiced everybody up.”)

But despite various recollections that Irlen and McKelvey had a blast on set, the two leads were the only people contacted for this story that declined to participate.

Reached for comment, McKelvey barked, “I’m not in the business anymore and I don’t like to talk about it.” He appeared as a villain in Carpenter’s “Small Kill,” and in the never-released 1998 comedy “Get a Job,” which starred many “Clerks” and “Mallrats” alumni. The only other public data on him reveals that he has worked in New York City as a bartender and brand manager, both as recently as 2016.

Irlen, when emailed for comment, called “On the Make” a “dreadful” film that “mercifully” never got a wide release. “To call what I did in it ‘acting’ is a bit of a stretch,” he added, politely declining to speak further about it. Irlen now works as a casting and talent agent, primarily for child and adolescent actors.

“Steve was very insecure,” said Kehr. “He was nervous all the time. He wanted to do a good job. I think he was 18.”

“There’s not an actor alive that’s not embarrassed about the beginning of their career,” said Melfi. “You have to start somewhere.”

“I can look at ‘On the Make,’ filled with mistakes, and it doesn’t threaten me, because I’ve done so much work,” said Hurwitz. “Maybe it’s threatening for Steve. I look at it and go, ‘That’s where I came from. It’s all part of where I am now. It’s life.’ We were all young and making a film that got released in theaters. To me, that’s an amazing feat.”

“Some people get negative, instead of saying, ‘You know what? I made a movie. And maybe it sucks, but it’s playing in 35 theaters. My name is on the billboard. That’s not so bad considering all these other actors are unemployed,'” said Carpenter.

“And on my father’s grave, Mark said [that shoot] was the best two weeks of his life,” he continued. “I have a feeling he and Steve were depressed after the movie was over, because they were treated so well. It was a nice, high-end club, it was cozy, they had food and drinks, they had girls. Everyone thought they’d be the new sex symbols. So maybe, to not get work after that, it must be hard.”

***********

After the edits were complete, Carpenter embarked on finding a distributor for “On the Make,” an experience he remembers as excruciating.

“I sent these companies VHS tapes, and they would send the tape back and say they watched it and didn’t like it,” he said. “[It was clear] that after five minutes, they just stopped watching it.”

Carpenter, already cynical about the studio system, never dreamed that his small film would show at a major theater chain. Fortunately, Stanley Dudelson of Taurus liked the film and felt “it needed to get out there,” Carpenter said.

“We were all very shocked by what Fred was able to pull off,” said Nogaro. “It was a real study in [what happens] when you set your mind to something, because he actually got way further than any of us imagined.”

“Fred was professional and stayed cool under the collar,” said Melfi. “When we actually finished it and got to screen it, we were so proud. We never took it for granted.”

Thinking back to the Philly screenings, Melfi recalled a far more positive experience—and certainly not fellatio in the back of an empty theater!

“I come from a conservative family, and there wasn’t that kind of stuff going on or I’d really remember it,” he said. “I took my family and friends [in Philly], and as rudimentary as [the film] is—you can only do so much with a budget like that—it still had an impact. Because [AIDS] was so scary at the time. Back then it was completely unnerving.”

McTernan was also pleased, for the most part. “I thought a couple of [jokes] were cute and others were maybe not as funny as intended. We were hoping to make the nightclub equivalent of ‘The Godfather,’ but we made ‘On the Make.'”

“But ‘The Godfather’ was not Coppola’s first film,” he added. “I really thought, for a first film, it was good.”

Others disagreed, to put it mildly.

“The movie turned out dreadful!” Nogaro exclaimed. “It was poorly acted. I walked away saying, ‘That was terrible, but hey, great first attempt.’ I don’t expect anyone to hit a home run out of the gate.”

“I thought it was gonna be a more powerful, meaningful film,” said Koury-Papa. “And as you saw what was going on, it was more sort of a comedy and sort of not a comedy. They really wanted to sell it as a very timely movie, so I don’t know if [the writers] were just capitalizing on the AIDS epidemic or if it was something they were genuinely concerned about.”

(“It had a really important message,” Carpenter responded. “I’m really proud of that. But do I [follow] club culture? No, not really.”)

“I took a date to see it in the theater [in New York],” recalled Royce. “I’m trying to impress her, that I’m in this movie that I worked on. It was maybe not a great date movie, because it’s a cautionary tale about not having sex randomly, you know? But she was a good sport about it.”

“The movie ends,” Royce continued, “and literally, the guy in front of me was like, ‘Well, that’s the worst thing I’ve ever seen!’ He turns around to me, as if to say, ‘Haven’t we all seen this terrible thing?’ And I’m like, ‘Yeah, I worked on it, and I was in it, but I respect your opinion.'”

That said, Royce was as impressed as his peers by the film’s ambitious goals.

“They really took a big swing, trying to make a comedy that had an AIDS message,” he said.

Sullo remembered a happier crowd response in New York. “The audience was very responsive, it was a lot of fun. It was mostly teens.”

Had “On the Make’s” release schedule been reversed, the film—which, with its characters’ “Lawn Guylind” accents and metrosexual cynicism, was tailor-made for New York-area youths—may have garnered enough word-of-mouth to yield better responses in secondary markets and, subsequently, VHS and DVD distribution. As mentioned above, the film was written about warmly, upon its NYC run, by the aforementioned Times reviewer Caryn James (who, despite a mixed overall review, lauded Hurwitz’s ability to take “an amateur film maker’s budget and [turn] out a professional-looking film”); The Village Voice’s Renee Tajima-Peña (who had recently directed the highly praised doc “Who Killed Vincent Chin?” and enjoyed “On the Make’s” “voluminous energy,” the “unaffected ease” of its young actors, and the script’s shirking of “pseudo-hip talk”); and Playboy’s late critic Bruce Williamson (who compared it favorably to the “slick vulgarity” of that year’s pizza-boy-turned-gigolo comedy “Loverboy”).

“It was the July 1989 Playboy issue. The cover said ‘Broadcast Nudes,’ [because] a woman newscaster was posing,” said Carpenter. “Williamson gave it two and a half bunnies. If he didn’t like [something], he just wouldn’t write the review. And he did that with other indie filmmakers, which I thought was very cool. If you’re doing what I do, the pen can fucking destroy you.”

Sadly, that’s just what the smaller city reviewers did, taking no mercy on the film’s humble background. The Philadelphia Inquirer called it “dreary and inane.” (Across town, the University of Pennsylvania’s newspaper, The Daily Pennsylvanian, didn’t bother to review it, though they published a cheeky blurb that may have tickled students’ fancies enough to venture out on opening night: “A nice, wholesome family film—take the kids; we’ll take the babysitter.”) Brutal takedowns in New Orleans’ Times-Picayune (“does everything—and I mean everything—wrong”), Miami’s Sun-Sentinel (“interminably unappealing”) and Tulsa World (which also used the word “interminable”) didn’t raise anyone’s spirits.

“I remember my friends’ parents went to see it in Jacksonville,” said McTernan. “I can see it not playing well [with audiences] there.”

“Most of the experience was, ‘Wait a minute, the sound system in here sucks, and the bulb isn’t bright enough,'” said Hurwitz. “When you have a dark bulb, all the color is muted, and everything looks soft focus-wise, and if the sound sucks, everything you did to mix it just goes out the window. So I understand why George Lucas created THX. There’s a need for some sort of conformity to present films in their best light.”

Overall, though, Hurwitz’s takeaway was positive. “At the end of the day, I got to make a movie that was in theaters! Odds are, at 52, I’ll probably never have anything in a movie theater ever again. So that’s special.”

As for the critics, Hurwitz said, “I don’t think I was ever hurt or destroyed by the bad reviews. I was inspired by the good ones. No one is owed a positive review. You can fumble and realign and redo and end up with something you worked hard on and put it out to the world, but there’s no guarantee that if you make a baby, it’s gonna be liked. I went in there blind because I’d never gotten reviews before. I don’t make movies to be popular and I don’t make movies to be liked.”

It remains clear that the film, however lukewarm the reception, didn’t kill anyone’s career. With a few exceptions, almost everyone involved seems to be excelling.

Carpenter is still widely celebrated in the tightly knit Nassau County film community, often featured on the local festival and television circuit. Though he never quite made the leap to the big time that fellow indie Long Island directors Rob Weiss and Hal Hartley did, he’s happy—mostly—to be doing what he loves.

“I never did drugs. I’m not really a drinker. I like movies,” Carpenter laughed. “My mother said to me once, ‘You know Alcoholics Anonymous? They should have a Movies Anonymous!”

If he were to make the film today, he’d take the five leading actors and “have them talk to the camera, about the guy dying of AIDS and why he got involved with these girls. Then the footage that I had would have been really fantastic. That film, right now, has its issues. But if I recut it now—the people in it are older now, they could talk about what it was like to be in the club. There’s so much you could do.”

Baltz will appear in the forthcoming “Kings,” starring Halle Berry and set during the 1992 South Central riots. Though he hasn’t thought about “On the Make” in almost 30 years, upon being asked for his reflections, he said, “It was fun, being dropped into it and kind of playing with it. I think it was one of those movies where a lot of people were learning how to do things. There was a lot of hard work that went into it.”

Most recently, Melfi worked on a pilot for Amazon, airing soon, called “Love You More,” directed by Bobcat Goldthwait and starring Bridget Everett of “Patti Cake$.” Before his “Sex and the City” breakthrough, he worked in various roles for a number of I.R.S. Media films, including “December” (“shot in the middle of winter [at Wells College in Aurora, New York]. We slept in the dorms. We were next to the lake, so the soundtrack was filled with geese.”); the very obscure George Segal comedy “Me Myself & I”‘ (“Segal was very Yiddish about it all. He’d say, ‘This is where I’m staying?’ I remember him never, ever not having a story to tell.”); and “Rage and Honor II” (“a kickboxing movie [shot] in Indonesia, I think for $400,000. It was a hideous experience. The [local] producer wanted another $400,000 out of the Hollywood producer, so we had to smuggle the negative out of the country!”) “Rage” also marked the second—and last—time Melfi appeared in a cameo, as a terrorist. (“I have the dark, swarthy thing,” he said.)

Thinking back to “On the Make” still gives Melfi “that curl in my stomach, that this is what I’m supposed to do. I still have a socialist attitude about filmmaking. ‘Above-the-line,’ ‘below-the-line’ is such bullshit. Everybody gets a turn at being important.”

And as for Hurwitz, he said his continuing love of film—and his early knack for directing—was the product of growing up, more or less, on his father’s films set.

“My earliest childhood memory was from the set of ‘The Projectionist.’ I must have been about two years old. I wanna say it was New Paltz, in Upstate New York. They put a cameraman out on a rowboat, to shoot from the water back to the shore, to these caves. I remember I couldn’t figure out how they rowed the boat backwards! Because that memory was kind of haunting, I held on to it. And that memory has a cameraman holding a camera in it.”

His dad, an avid movie collector and later a film professor, turned Hurwitz on to Charlie Chaplin and other silent greats, to Woody Allen, to Stanley Kubrick, to Ernst Lubitsch—all at an impressionable age. But perhaps the greatest piece of wisdom he left behind was expressed in an interview—shortly before his death in 1995—that was published in Michael Singer’s 1998 collection “A Cut Above: 50 Film Directors Talk About Their Craft.”

“He said, ‘I’d rather make bad movies than do good teaching.’ And I get that,” said Hurwitz. “I’ve worked on probably over 600 films as a behind-the-scenes producer, for some of the most amazing filmmakers, on some of the most incredible movies ever made—and some of the worst. And even a bad movie is amazing, the fact that it gets made.”

Very nice. I would like to see this movie. Hopefully, maybe Arrow or Vinegar Syndrome can acquire it. Also, as of 2021, the OFG catalog appears to now be with FilmRise.